“The theme of the [Mars and Venus] together with the identity of its recipient [Francis I] and the context of sophisticated culture, stimulated a recollection of the manner Rosso had used in his designs for mythological engravings in Rome, but he has infused this with the brittle brilliance of his re-won Toscanità, and with a higher stylization, elegant as well as precious, of the theme and form. The drawing attains the precise style that Rosso was to employ at Fontainebleau, …

“The temperament that bred Rosso’s radicalism, however, also made his art so personal and extreme that, despite the power of its invention and ideas, it lay towards the periphery of the main historical development. In France there was no historical framework to which Rosso’s art referred; it was his art that created it for the subsequent French sixteenth century.”1

Sydney J. Freedberg, Painting in Italy 1500–1600, 1971

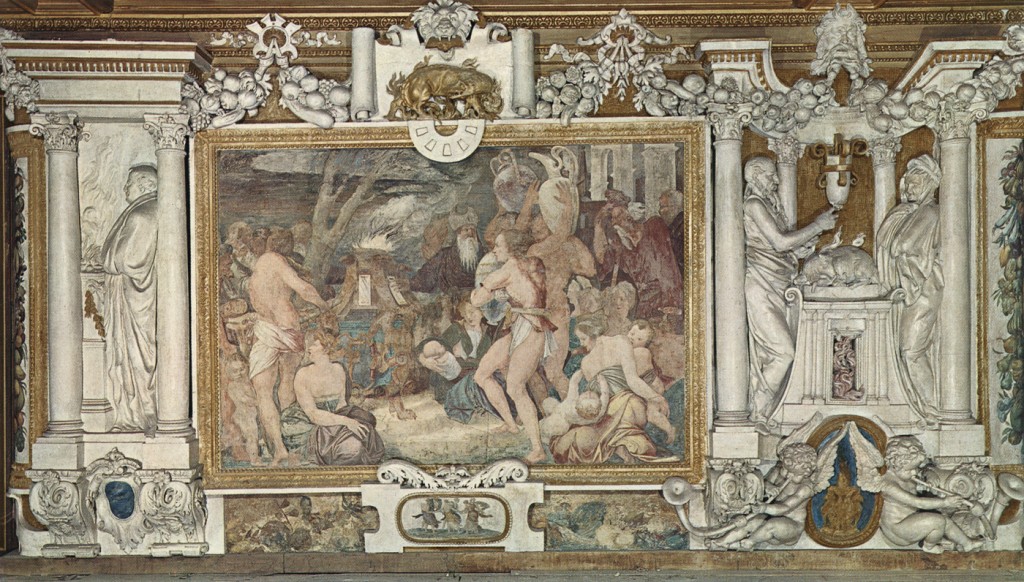

Rosso’s career in France presented no more of a clear sequence of events than was presented by his varied and sometimes contradictory activity in Italy. Although it might be supposed that his support by such a grand patron as the king of France and his removal from the important artistic centers of Italy would have channeled his talents into a consistent manner of expression—a view that seems vaguely held about Rosso’s work during his years in France—the surviving evidence indicates that such was not the case. The opportunity and inclination to shift from one artistic mode to another and from one kind of emotional expression to another continued. And now, it appears, Rosso could even more freely invent without the threat of censure. For he alone was bringing the grandness of Italian art to France and no one there had the comparable artistic knowledge to judge his performance. At the same time, however, his artistic expression underwent a process of maturation that followed through the new and sophisticated tenets it had acquired in Rome and that, to a limited extent, was modified in the Umbrian and Tuscan towns to which he was confined before his departure for France. While the changes to his art, since 1524, tended to reduce its emotion and frequency of stylistic change, in France Rosso’s art eventually assummed again some of its pre-Roman feeling and range of expression.

The visual evidence of Rosso’s French career is extensive. It is largely in the form of prints and drawings, which must be considered to the same extent as the sculpture and paintings in the Gallery of Francis I at Fontainebleau and his two surviving French easel pictures in Paris and Los Angeles. There is also the evidence of his activity as an architect of lost and surviving buildings. All of this material supports Vasari’s claim at the beginning of his biography of Rosso of 1550 that, “la gloria di lui [in France] pote spegnere la sete in ogni grado di ambizione, che possa il petto di qual si voglia artefice occupare.” Vasari went on to say that, “sopra un’altro del suo mestiero, da si grand Re come è quello di Francia, fu ben visto, & pregiato molto.”2 At the end of the enlarged biography of Rosso published in 1568 Vasari added that when the news of Rosso’s death was taken to Francis I, “senza fine di dispiacque, parendogli aver fatto nella morte del Rosso perdita del più eccellente artefice de’tempi suoi.”3

The earliest reference of Rosso in France places him there in November 1530. Vasari wrote that Rosso went to France from Venice, which it can be safely assumed was the last place of his artistic activity in Italy.4 The iconography of the Mars and Venus drawing in the Louvre—the drawing, in all likelihood, that Vasari said Rosso made in Venice—supports the probability that his French career was indeed launched from that city with the help of Aretino who “in 1529… attached himself to the circle of scholars and artists formed by Lazare de Baif, the French ambassador to Venice.”5 Lazare de Baïf, who was to be contacted from France on Rosso’s behalf a year or two later (DOC. 14), may very well have had a role in Francis I’s decision to call Rosso into his service.6 That the king himself called the artist is specifically stated in the letters patent he received from Francis I in 1532 (DOC. 24). It was Baïf who had written to Francis in October 1529 to tell him of the possibility of attaching Michelangelo to his court at the moment that Michelangelo, in flight from Florence, was in Venice and thinking seriously about going to France. However, he left Venice and was again in Florence around 20 November, 1529.7 At this time Rosso was in Borgo Sansepolcro, having fled from Arezzo in mid-September.

In the 1568 edition of the Vite, Vasari says after his comments on Rosso’s activity in Sansepolcro: “Ora avendo egli sempre avuto capriccio di finire la sua vita in Francia, a tòrsi, come diceva egli, a una certa miseria a povertà, nella quale si stanno gli uomini the lavorano in Toscana a ne’paesi dove sono nati, delibera di partirsi; ed avendo a punto, per comparire più pratico in tutte le cose ed essere universale, apparata la lingua latina, gli venue occasione d’affrettare maggiormente la sua partita;” whereupon follows Vasari’s story about the argument with a priest on Maundy Thursday and Rosso’s flight … “facendo la via di Pesaro, se n’andò a Vinezia.”8 Because Vasari wrote “come diceva egli” there is reason to believe that he is recalling sentiments about misery and poverty that Rosso actually expressed to him in 1528 in Sansepolcro and Arezzo.9 At the same time, he may also have learned from Rosso of his “capriccio” to spend the remainder of his life in France. That he actually was preparing himself for a career in that country, as further suggested by Vasari’s remark that Rosso was educating himself for such an eventuality, seems, very possibly, also indicated by the nature of several possessions that Rosso left behind in Arezzo in 1529: “uno Plinio legato in assi”, “uno Sepontino legato in assi” [referring to Niccolò Perotti, Archbishop of Siponto, and hence probably to an edition of his Latin grammar, Rudimenta grammatices], “uno libro vocato ‘il Cortiggiano “‘, and “uno Victruvio sciolto” [Vitruvius’ On Architecture] (DOC. 13). Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano had only very recently, in 1528, been published for the first time by Aldus in Venice. As it is possible that Pietro Aretino, who might have met Rosso in Rome in 1524 or 1525, was in correspondence with him when he was in the former’s native town, it could have been Aretino who had sent Rosso a copy of Castiglione’s book. A relationship between these two men before the spring of 153o would account for Rosso’s trip to Venice to see Aretino as a means to gain employment by Francis I. On his way he would have stopped at Pesaro not to seek employment but to see what artistically was going on at the Villa Imperiale—not unlike what would be required at the château at Fontainebleau, at this moment in the process of being enlarged. Later, on his way from Venice to France, he could easily also have stopped at Mantua to see what Giulio and his young assistant Primaticcio were doing at the Palazzo del Te.10

Arriving in Venice, probably at the end of April 1530, it was only six months after the time that Baïf had written to Francis I about Michelangelo, who, however, was on his way back to Florence before the king’s reply was received. Consequently, the spring and summer of 1530 were very much the time for Aretino to push his advocacy of Rosso.11

What may have been a “capriccio” of Rosso’s in 1528, or even earlier, could have already become a more substantial possibility in Arezzo in 1529 through Aretino’s solicitations. If such was the case in 1529 it might be another reason, in addition to the one mentioned by Vasari that Rosso “fu sempre nemico del lavorare in fresco”, for Rosso’s dilatoriness in Arezzo over the S. Maria delle Lagrime project. The possibility of his leaving Italy could also account for something of the slack character of some of his later Italian inventions. It might, too, partly account for the changes of the Christ in Glory from the complex composition seen in the early drawings to the rather rigid symmetry of the finished picture. One cannot help but wonder again why specifically Rosso did not, after Rome, settle again in Florence. He sought instead employment elsewhere and yet a man of his talents and background might be expected not to stay for long at the peak of his powers in the limited environments of Borgo Sansepolcro, Città di Castello, and Arezzo.

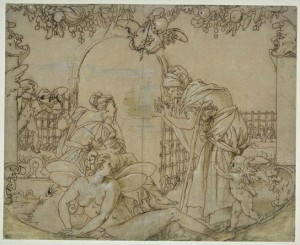

The attenuation of Rosso’s talent, if such is what can partially be recognized as an element in a few of his late Italian works—and at this moment it is sometimes talent more than genius that seems to be an issue here—was not to remain for long a condition of his art. Certainly the stylistic brio of the Mars and Venus drawing gives evidence that Rosso’s powers of artistic inventiveness were not seriously impaired for long. The artistic character and quality of this drawing are, in spite of the difference of subject, identical to those of his Pietà in Borgo Sansepolcro. There is in the drawing some of the same distancing of real emotion and the same kind of replacement of the latter by studied rather than felt poses and gestures. Whatever these may mean in the Pietà, in the Mars and Venus, destined almost certainly for Francis I, they would have conveyed and signified to the king something of the range and quality of Rosso’s talent without, however, revealing to the French monarch what deeper and more passionate concerns had been at times the substance of Rosso’s art.

UNE GRANT TABLEAU

The earliest document concerning Rosso’s residency in France that records payments to him “pour son entretenement” in Paris from November 1530 though July 1531 states also that “durant lequel temps it a fait ung grant tableau pour le Roy (L.45).” Francisque Scibec de Carpi was paid for making the wood frame for this picture and Jehan Poulletier for the gilding of it between 8 and 17 July. In addition “Archangelle de Platte” was paid “pour ung voiaige dudict Fontainebleau à Paris, pour faire venir led. tableau.” It can be concluded from this information that Rosso’s large picture was painted in Paris and sent to the king who was living in Fontainebleau in July and August 1531. Unfortunately, the subject of this picture is not mentioned but we know that Rosso was again active as an artist soon after his arrival in France, and that he was occupied with a commission for an easel picture, which, though executed in Paris, was sent to Fontainebleau. There is no evidence, however, that this framed painting was made for any decorative scheme at Francis I’s château.

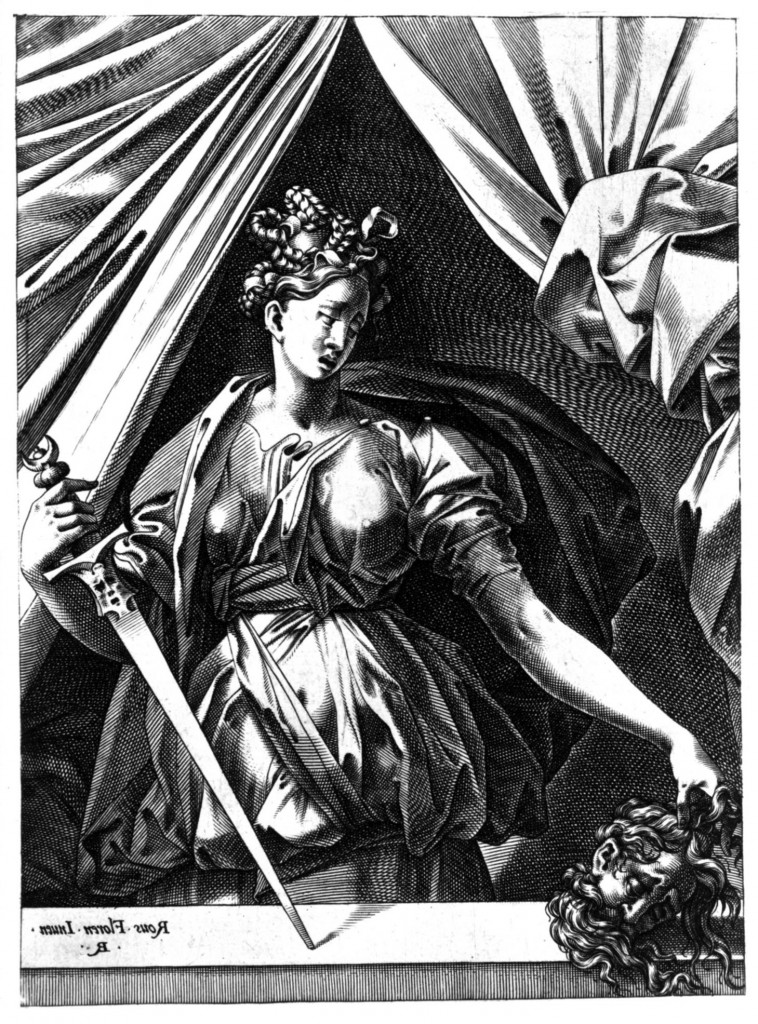

JUDITH

It would have been about now that Rosso painted the lost Judith (L.35) that is known from an engraving by Boyvin. This print almost certainly reproduces, in reverse, the composition of the panel picture that Cassiano del Pozzo saw at Fontainebleau in 1625 and which he described as “grande poco men del vero”. Given this remark, and what we see in Boyvin’s print, the lost Judith must have been almost a meter and a half high by around a meter wide. It could, therefore, very well have been the “grant tableau” that Rosso made for the king in 1530–1531, and for which Scibec de Carpi carved a frame that was then gilded.

Stylistically the Judith, as we can judge it from Boyvin’s reproduction probably made from a lost drawing by Rosso for his picture, so closely resembles the Mars and Venus drawing that very little time could have separated the creation of these two works. The picture must have fulfilled in painting what Francis I would have expected of Rosso from the drawing made just before he arrived in France. But, as the style of that drawing was itself not absolutely novel in relation to the style of Rosso’s earlier art, so too the Judith has close stylistic precedents in Rosso’s late Italian works. The young heroine in the engraving corresponds to the woman in the drawing in Rome for the Christ in Glory and to Eve in the Uffizi Allegory of the Immaculate Conception made for S. Maria delle Lagrime. In all likelihood the execution of the Judith painting was very much like that of the Città di Castello altarpiece.

What the Judith shares especially with the Mars and Venus is the particular elegance of elongated proportion paired with graceful limbs and posture of its figures. There is also in both an expression of almost painful seriousness. Judith, standing in back of a parapet, derived possibly from Venetian art,12 and under the parted curtains of what is probably meant to be Holofernes’ tent but also serve as a canopy for the figure of Judith. Behind her can be glanced the drapery of Holofernes’ bed. Judith holds his severed head at arms’ length, a head so small as to prevent too vulgar a reference to the actual horror and heroism of her act. Yet, compared to the richly filled and complexly composed Mars and Venus, the Judith is a simpler and even a more eloquent work of art. While this is partly true because it presents but a single figure and also, in its greater simplicity, very probably because of Boyvin’s reduction of the fine nuances of Rosso’s original drawing for his painting, it is nevertheless observable that the spacing of the elements in the Judith also reveals a clarification of style of the Mars and Venus. The rumpled curtain on one side of the composition complements the drama of Judith’s glance and gesture of holding Holofernes’ head. The other curtain, pulled straight, meets the oppositely slanted diagonal of the sword that Judith holds, the hard and pointed character of which heightens the supple appearance and grace of her extended parallel arm. It is possible that the forms in Rosso’s drawing were plastically fuller and more continuous than in the Venetian drawing, although this apparent difference may have been, partly at least, provided by Boyvin’s engraving.

For the fullest understanding of the picture Boyvin’s print must be reversed. In this direction Judith holds the sword in her right hand making it the major symbol of the picture. It is gently held in her hand without any indication that it had been used in the violent decapitation of Holofernes. She looks with distain at Holofernes small head set at the far right upon the ledge before her. The tip of her large sword touching this ledge near the center of the picture gives a sense of poignancy to the image but, again, not of violence. Although without the representation of the actual narrative of the beheading of Holofernes the story implied to the knowledgeable viewer in all picture’s details. Judith’s coiffure may still reflect a recollection of Michelangelo’s and Rosso’s own teste divine but it seems here more exotic to further indicate that, as told especially in St. Jerome’s version of the Book of Judith in the Vulgate, that she had prepared for her visit with Holofernes in a seductive manner not those of a devout and modest widow. The light on her left breast, almost at the very center of the composition, and the very evident nipples of both breasts suggest the sexual encounter that lay behind Judith’s intentions.

It is with clear intentions that what may be Rosso’s first work for Francis I is an image of a woman, and of Judith, both beautiful and brave as the defender of her people. The sexual allure of Judith would be anticipated to please Francis as would the indication that she is the savior of her people. The subject could also have been intended to supplant the image presented by Rosso’s Mars and Venus of a hero too under the sway of a woman’s amorous intentions.

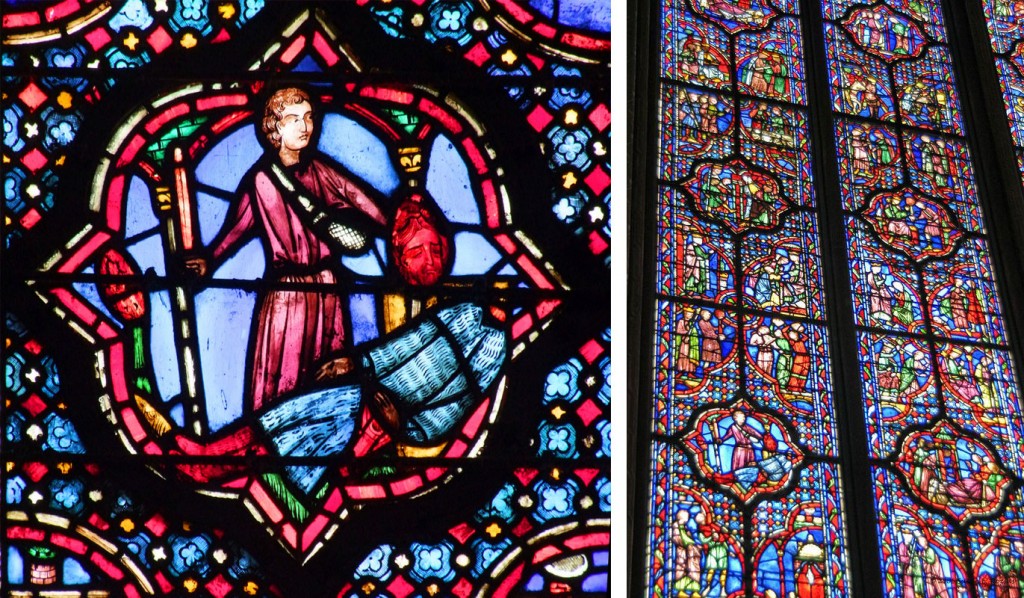

But Rosso’s is a rare image of this heroine, “rarely seen in French literature before the sixteenth century” or in the visual arts in France. Images of Judith of the sixteen century in France do not appear in any of the fairly numerous recent publications on her although some as stained glass windows can be found online (at judith2you).

[Fig. Church of St. Martin, Triel-sur-Seine]

Around 1500 Judith was the subject of a theatrical drama attributed to Jean Moliner, Le Miroir des vefves; Tragédies sacrée d’Holoferne & Judith and appeared in collected biographies of famous women such as one by Alfred Dufour in 1502. Already in the mid-thirteenth century Judith was identified with the French monarchy in forty panels of a window in Sainte-Chapelle in Paris devoted to her story as part of the narrative of sacral kingship. But her royal appearance at Sainte-Chapelle has not yet been studied in its subsequent importance and Rosso’s depiction of Judith appears unprecedented in France.

[Center Fig.Judith and Holofernes,Sainte-Chapelle]

But in Florence the heroine as savior of her people was a frequent subject of art and could have been easily recalled by Rosso and other Italians at the French court when the artist was seeking a subject for his painting. There is every reason to conjecture that he knew the depictions of Judith’s story in the panels at Sainte-Chapelle and became aware of their importance in his need as painter to the king to identify with the French monarchy. Judith was also seen as defender of the Faith and became a symbol of it in the later sixteenth century for both Catholic and Protestants. What seems to be the earliest French work by Rosso shows him establishing his new position as painter to the King of France, already suggested in the Venetian Mars and Venus drawing, and to the French monarchy.

Judith was presented as La Femme Forte in Abraham Bosse’s engraving published in Paris in 1645 in an image that could just possibly reflect knowledge of Boyvin’s print.

[Center: Fig.Abraham Bosse, Judith]

At the time that Rosso executed his “grant tableau pour le Roy” it had been two or three years since the rebuilding of the château at Fontainebleau had been prescribed, in April of 1528, with the construction placed under the supervision of the master mason Gilles Le Breton.13 Rosso’s activity as a decorator there does not seem to have begun until late 1531 or in 1532, although he would almost certainly have become acquainted with the tasks that he would have to face at Fontainebleau immediately upon his arrival in France. It is very probable that he knew where his large framed picture was going to hang in the château even though he may not have actually designed the setting for it. This would be distinct from the frame carved by Scibec for which Rosso could have supplied the design, as later he did for the frame of Michelangelo’s Leda.

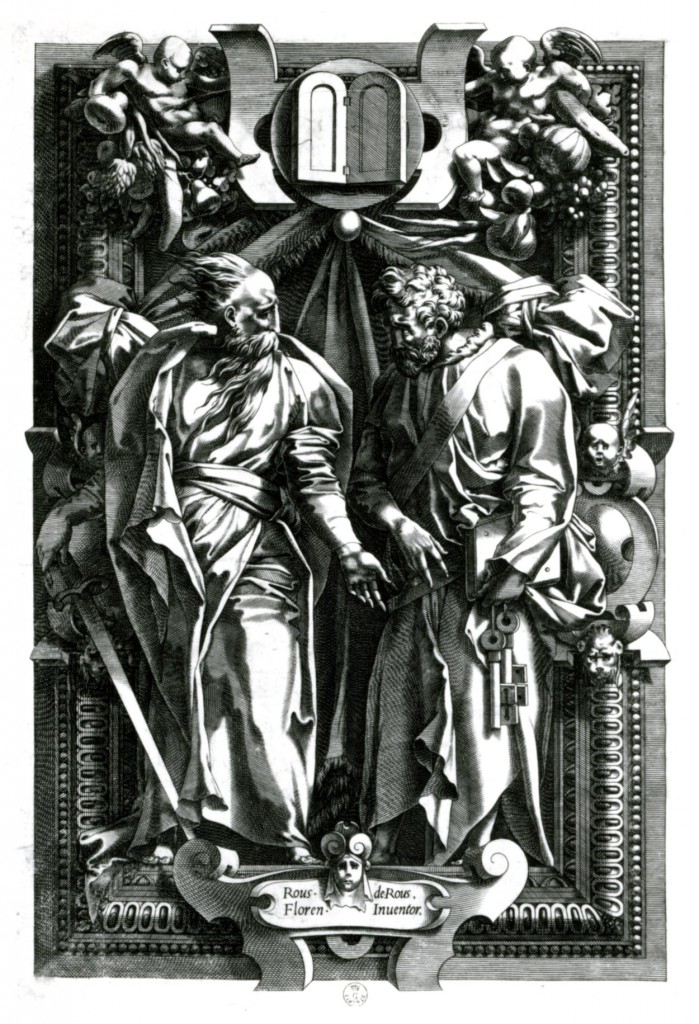

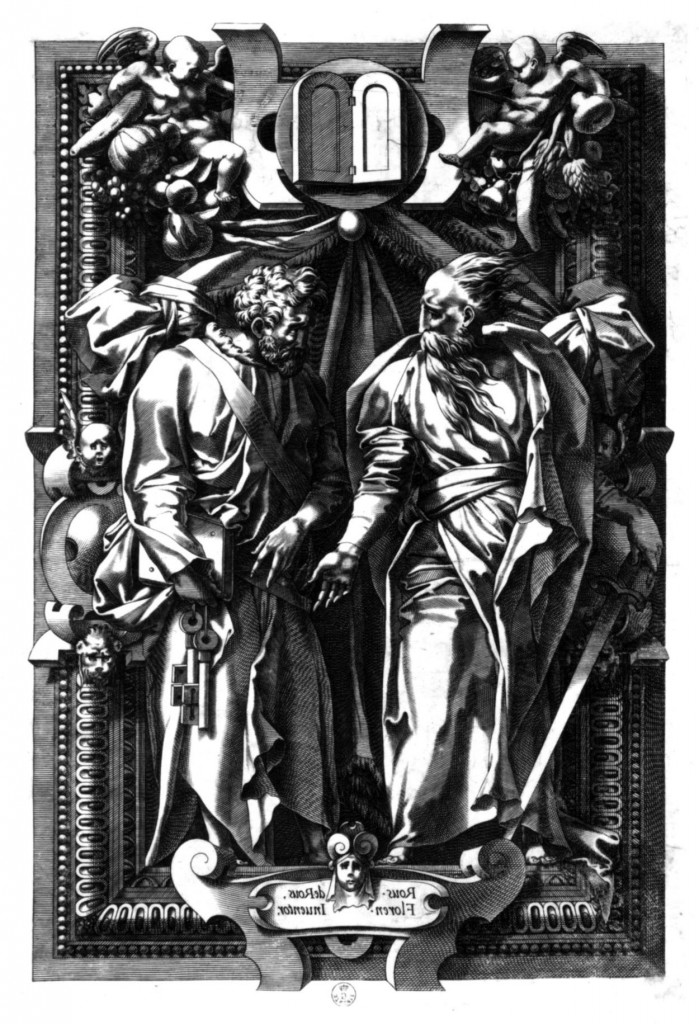

Another image engraved by Boyvin, or by someone in his shop, and showing a disputation between Saint Peter and Saint Paul, could also be associated with the rise of the Protestant movement just at the time Rosso arrived in France.

Stylistically the image gives, as in all Boyvin’s engravings after drawings by Rosso that survive, an accurate record of another lost drawing by Rosso done about the same time as the lost original drawing used for Boyvin’s Judith. The forms in the engraved St.Peter and St. Paul have the same kind of emphatic plasticity and similar composition concentration that, however, is increased in the St. Peter and St. Paul by its very restricted space. The pairing of the two saints in conversation and the intensity of their discourse bring to mind Rosso’s Florentine Disputation between Old Men of around 1518 (Fig. D.2). Also that year Agostino Veneziano engraved Rosso’s Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil. In the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece a dispute appears between the young St. John the Baptist and the old and bare-chested St. Jerome. Rosso’s St. Peter and St. Paul presents a return to this aspect of the Florentine years.

In the figure of St. Paul there is also a recollection of his Standing Apostle of around 1529 in the British Museum (Fig.D.36). But there is a stillness and a disembodied quality about that elegant figure that have given way in the figure of St. Paul to a physical and passionate physicality of the two saints that is unlike the planar character of the figures in the earlier drawing. The St. Peter and St. Paul also appears more vigorous than the Judith that is probably slightly earlier in date.

St. Paul, gesturing toward St. Peter (in the lost original drawing with his right hand), would be arguing, with reference to the pair of rounded slaps above that signify the Mosaic Tablets of the Law, his position on issues that were brought up first at what is often referred to as the Incident at Antioch.14 Peter is listening intently, his Keys of the Church appearing in bright light. (Paul’s sword is half in show.) Paul held the position that Gentiles converting from Paganism to Christianity need not be circumcised or follow the dietary laws of the Jews and the Laws of Moses. The main sources of this famous incident are Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, 2:11–14, his Epistle to the Ephesians, 2: 11–22, and the speech of Peter and the decision of James the Just in the Acts of the Apostles, 15: 7–11, 19–20. Here the law of the commandments is made void and both the Jews and the Gentiles who are converted to Christianity are brought together “that he might make the two in himself into one new man” (Ephesians 2: 15). Also fundamental to the understanding of this Incident is the authority held by the Church of disputation itself. The strength of this authority that goes back to St. Augustine’s original disputation, is enforced by the authority of Rosso’s image. [ADD INFORMATION: see 1530 translation of bible and rise of Protestantism in France]. The engraving gives no indication of a conclusion that is reached by the disputants. In this respect Rosso’s St. Peter and St. Paul could have been meant to offer the viewer a sense of the Church’s ability to face, with the strength of its historic authority and responsibility, the threatening issues of Protestantism. That authority reached a turning point early in the French Reformation when “the king and his courtiers manifested their orthodoxy after the Affair of the Placards,” during the night of 18 October 1534, in a procession held in Paris on 21 January 1535.15 This authority and its orthodoxy may have gathered strength by the publication of the first printed translation of the Bible into French by the French theologian Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples in 1530 in Antwerp.

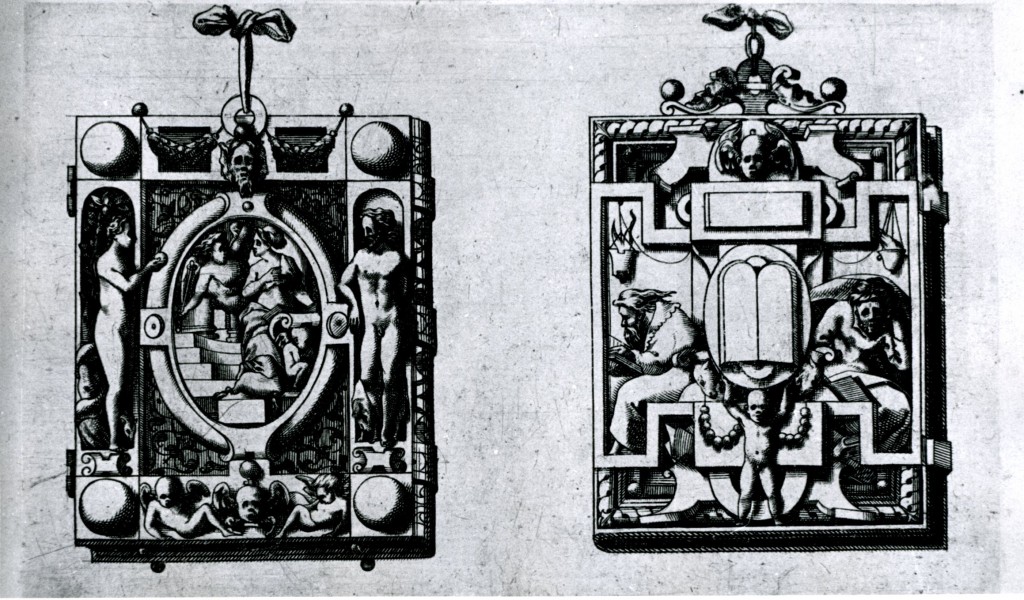

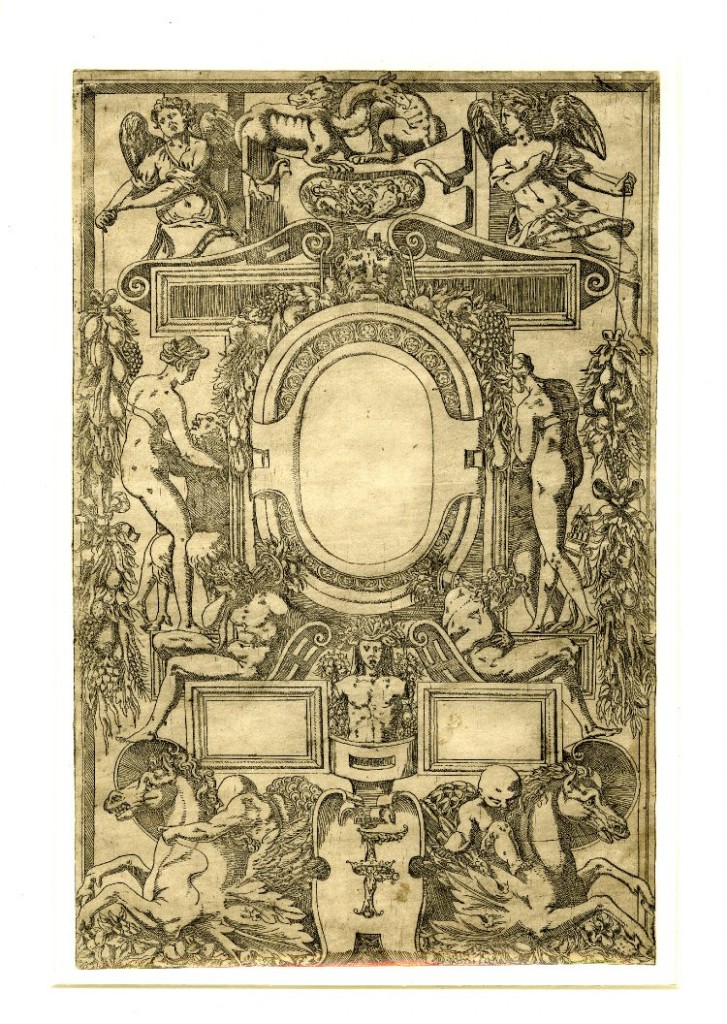

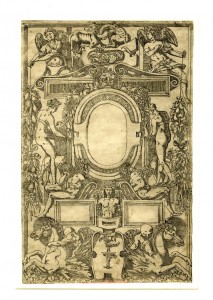

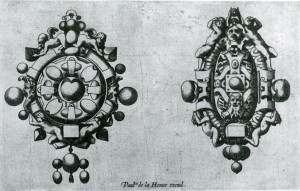

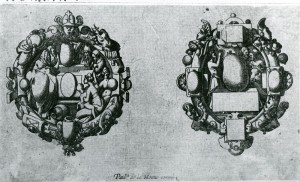

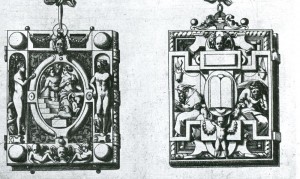

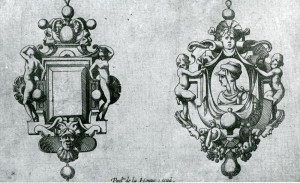

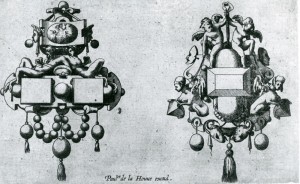

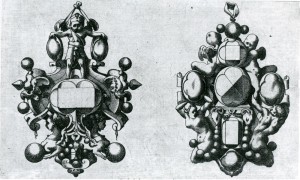

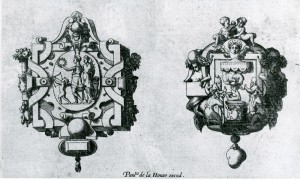

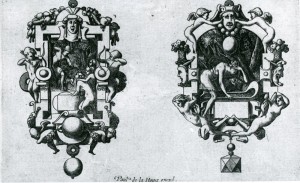

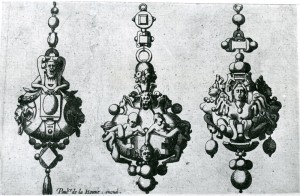

The importance of this engraving, or more importantly the lost drawing by Rosso from which it was made, in relation to confronting Protestantism can be seen also in the designs of two pendants referring to the New and Old Testaments, which are actually the covers of miniature books. The cover of the New Testament shows the naked figures of the Temptation of Adam and Eve standing at either side of an Annunciation set in an oval, while the cover of the Old Testament has set at its center the Tablets of the Law with a seated bearded scholar studying a book at either side. The appearance of these tablets to signify the Old Testament has its correspondence in the St. Peter and St. Paul to indicate the context of the disputation that is shown below them. That these small testaments are conceived as pendants seems a remarkable expression of piety of the person who would wear them.16

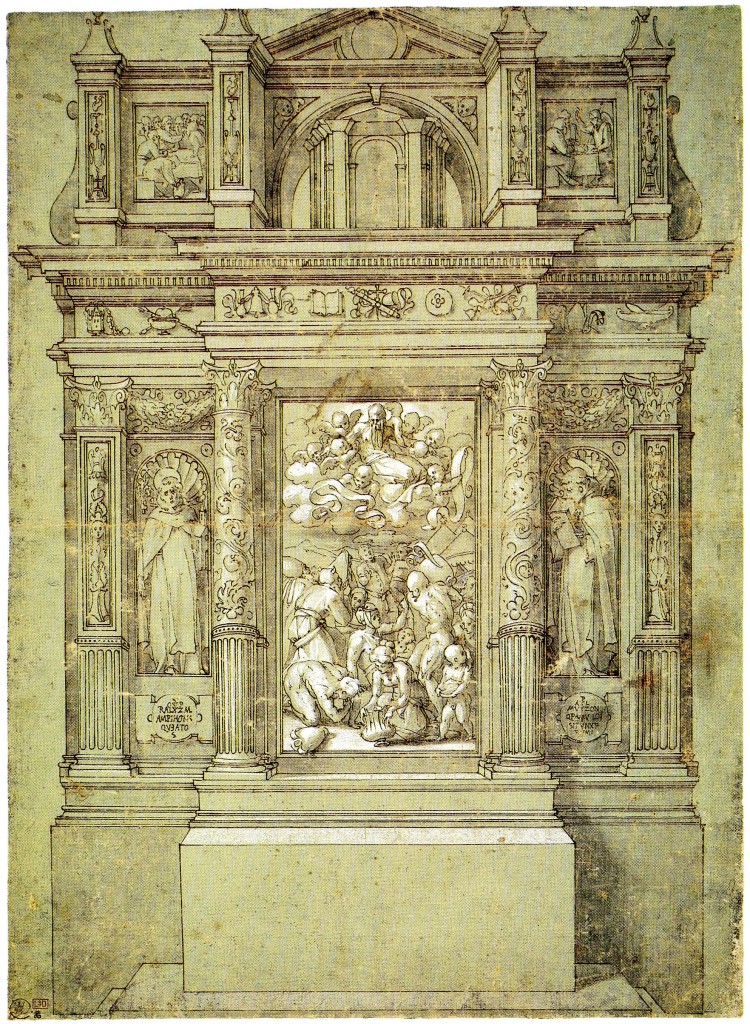

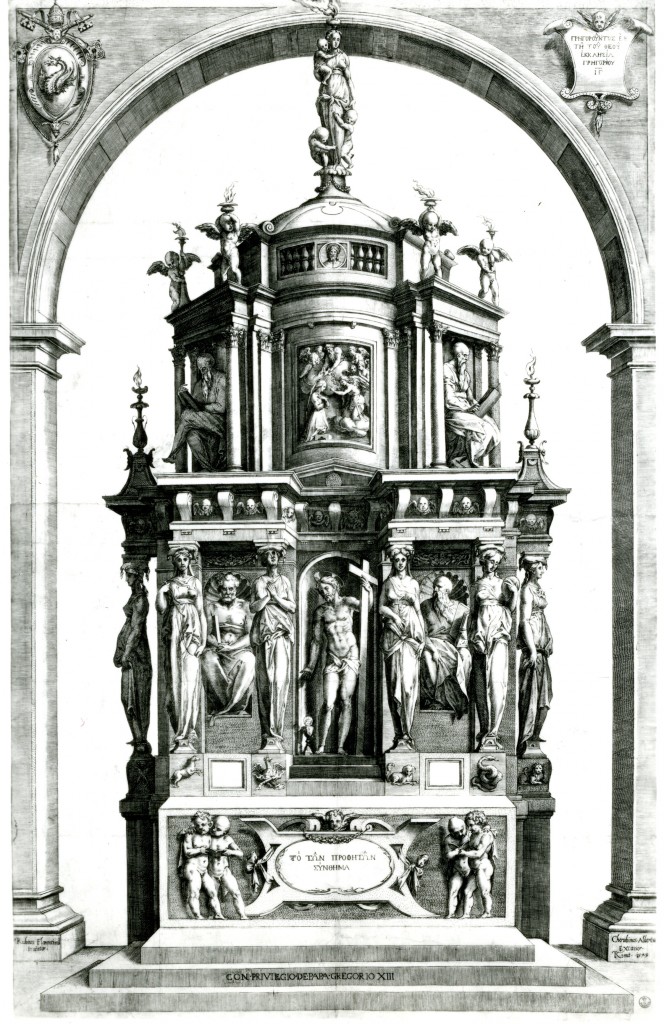

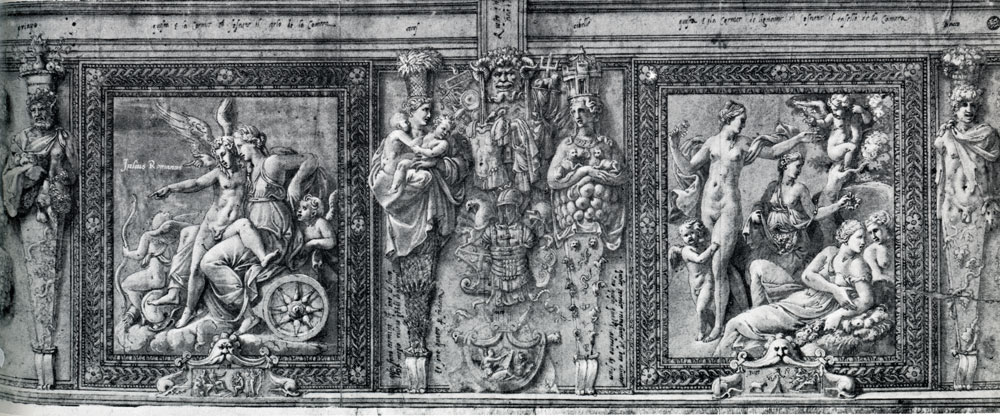

Zerner pointed out that the St. Peter and St. Paul looks like the design for a relief rather than a painting. The limited space of the composition, as well as its decorative forms and their relationships, could support this suggestion. But the original drawing may have been meant as the model for an engraving, the medium of sculpture imitated instead of illusionistic painting to give a sense of solidity to the concept of the image. However, as a relief, actual or imitated, the design gives evidence of Rosso’s concern with sculpture early in his career in France. In Italy he had given some consideration to the design of sculpture, not only in his pictures and drawings, but in images for actual sculpture. In Florence in 1515 he had designed a triumphal arch that was surmounted by a sculptured group and that also had painted sculptured stucco festoons of pomegranates and pine cones (L.9). Furthermore, we know he was commissioned to design the stucco decoration of the Cesi Chapel in Rome (P.16). The Design for a Chapel (Fig.D.37) is his earliest surviving Italian architectural project that contains sculpture set within it. Only slightly later in the Design for an Altar (Fig.D.38) does he use sculpture more extensively and imaginatively set within the architecture and as architectural elements themselves.

Whatever its ultimate realization, should that even have been a painted imitation of sculpture (as may have appeared on the Florentine arch), the whole conception of the St. Peter and St. Paul is plastic. This includes not only the two figures of the saints, but also all of what might be considered the decorative elements of the composition. Only the fringe on the curtain behind the saints seems pictorial in its definition. The saints are set within but also very much in front of a large rectangular frame made of flat and carved moldings more or less classical in inspiration. Attached to this frame are four large decorative units composed of abstract planar forms and realistic elements. From the unit above, and attached to it presumably by a large bead, hangs the fringed cloth that falls behind the saints and is tied back at the sides. By their size the saints dominate the composition, but the surrounding elements, because of their plasticity, richness, and density have their own artistic emphasis. Not in the least is this true because of their novelty.

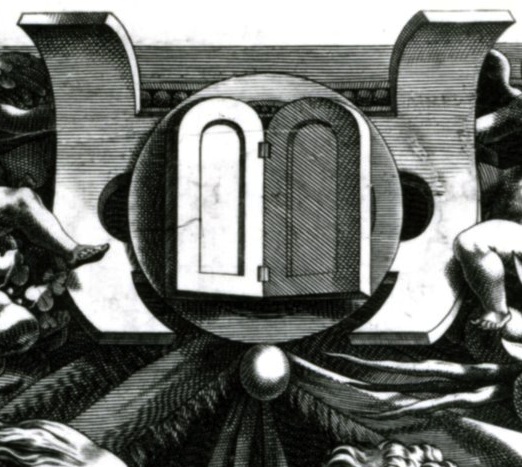

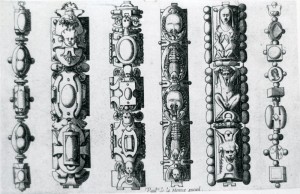

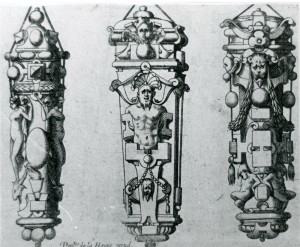

The large motif above is composed of a broad lyre-shaped element, the top and bottom of which are bent forward. On this element is placed a large round disk under which is a barely visible flat disk with a beaded rim. Upon this base is set a pair of blank hinged tablets that resemble the Tablets of the Ten Commandments. Flanking this large central motif are two winged cherubs leaning back on garlands of fruits and vegetables. The smaller motifs at the sides of the saints are composed of similarly cut and bent elements with a winged cherub’s head above and a lion’s head below each. Beneath the two saints is another decorative motif composed of fiddlehead shaped volutes, a broad rounded disk bent forward at the sides, and a head with a curled headdress and a cloth hanging down behind it. These decorative elements are unusual and seem little related to the vocabulary of decoration that Rosso would have known in Italy or met with in France. The broad, sharp-edged, curved, and bent forms do not appear strictly architectural in their origins but neither do they seem to come from the grotesque ornament derived from ancient Roman painting. In fact, their size and large planarity makes them seem not to function merely decoratively although they are attached to the richly ornamented frame of the composition. Like the vocabulary to describe them, these large motifs are musical in origin (of string instruments) and offer the implied resonance of sound to the voice of Paul. ADD Figs. of 16th c. instruments and their parts.

The uppermost unit is clearly emblematic with the Tablets of the Law appearing as a device against the field provided by the disc and lyre-shaped element, and this whole center piece is flanked and partly held in place by winged cherubs, which appear frequently in the display of coats-of-arms. Although unusual because they are composed of vegetables, swags, too, are common armorial accessories. The decorative units at either side of the saints also look emblematic, each composed of a shield-like center held in place by a bracket above and below and with a cherub’s winged head at the top and a lion’s head below. The latter might refer to the Throne of Solomon. The large unit beneath the saints forms a decorative base to the composition; its lower extensions are flat on the bottom and the side volutes are extended upward from that base, giving this piece the aspect of the bridge of a stringed instrument. To it is attached the decorative head and the plaque inscribed with Rosso’s name, an inscription that may not have appeared in Rosso’s drawing.

Shearman suggested that the kind of planar curved elements that can be found in the St. Peter and St. Paul have their source in the small tongued plaques of grotesque decoration as Sarto’s in the Scalzo in Florence and in the similar plaques of the ornament by Feltrini on the ceiling of the Cappella del Papa in the cloister of S. Maria Novella in Florence. SCAN FROM COSTAMAGNA P.117 (Fig.Feltrini)17 Plaques of this general kind do appear at the Scalzo and the small head at the bottom of the St. Peter and St. Paul is similar to some of the heads in Feltrini’s decoration. In Rosso’s own earlier work there is a plaque of similar kind attached by ribbons to the front of the priest’s headdress in the Marriage of the Virgin of 1523. This plaque may be bent forward along the top. It is possible that such elements by Sarto and Feltrini stimulated the creation of the larger motifs of planar and more flexible bent forms that characterize Rosso’s decorative system in his St. Peter and St. Paul and in the Gallery of Francis I. But these small-tongued plaques may not be the only source for his very bold ornamental devices.

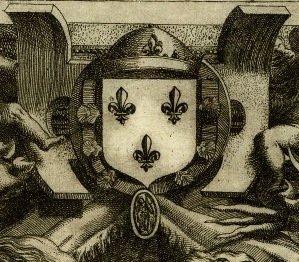

Closer to the flat and bent shapes that appear in the St. Peter and St. Paul are those of some early sixteenth century shields that support coats-of-arms. The Medici emblem of the arms of Leo X on the vault of the central bay of the Vatican Loggie are affixed to a sculptured shield, the four upper corners of which are split and curled forward as two flat-surfaced volutes. These forms do not, however, resemble the kind in Raphael’s painted and stucco grotesque decoration. Another coat-of-arms of Leo X in a drawing in the Louvre given to Feltrini has a viol-shaped shield with the broad upper and outer elements curled forward in a scroll-like manner.18 The actual carved shield of Leo’s arms on the portico of SS. Annunziata is similarly viol-shaped, with the upper parts curled forward and backward.19 Beneath the oculus in one of Pontormo’s lunette drawings in the Uffizi for Poggio a Caiano, the Medici balls are placed on a shield with four broad extensions that are curled backward.20 Similar shields can be found elsewhere early in the sixteenth century.21 It may be relevant, here, to recall that in 1513 and in 1515 Rosso was paid for executing several coats of arms at SS. Annunziata (L.4, L.6, L.8).

While it is not certain that the St. Peter and St. Paul is the earliest surviving example of Rosso’s work showing an extensive use of this kind of decoration, the conciseness of each unit of it suggests the beginnings of its use. (Only the vase in the foreground of the Gathering of Manna of Rosso’s Aretine Design for a Chapel and the ribs of the dome of his Aretine Design for an Altar suggest something similar before he went to France.) The completeness of each unit and its attachment to the frame in the St. Peter and St. Paul also support the probability that they are, in their shapes, related to shields. When such units become more complexly joined with a wider variety of motifs it still may be necessary to recognize some implied emblematic meaning in them. Although these decorative units in the St. Peter and St. Paul would appear to date early in Rosso’s French period, their invention is not in the least tentative. The shapes of which they are composed and their interrelationships are precisely determined to create a new kind of decoration that seems truly inspired. Detached from the flora and fauna of antique grotesque decoration and from its lightness of effect, Rosso’s decoration has the abstract force of a blazon, but with an accompanying enigmatic wit. The decoration is both abrupt and lyrical, with certain of its forms cut off sharply while others terminate in finely fashioned curves. To them are attached or associated heads and figures and garlands, but these only emphasize the fundamental abstraction of the basic forms. These are sculptural in their conception even though in the St. Peter and St. Paul they must be appreciated in pictorial translation.

It may be to the point to consider if Francisque Scibec de Carpi had any part in inspiring the invention of Rosso’s decorative scheme. We know that in 1530 and 1531 Scibec made the carved frame for a picture by Rosso (see L.36), and he may have carved the elaborate frame that Rosso designed for Michelangelo’s Leda in 1532 (see L.38 below). He could also have provided the “model d’une sépulture” (L.37) for which Rosso was paid in 1531. Later, Scibec carved the wood paneling in the Gallery of Francis I with its elaborately shaped and curled armorial shields that are set within a decorative context of the paneling that is not of Rosso’s design. It might have been through Scibec’s escutcheon designs that Rosso was inspired to invent his wholly new kind of decorative scheme. This association with Scibec may explain why this kind of invention occurred and took hold in Rosso’s art at this early time in France.

The frame that Rosso had made in 1532 for Michelangelo’s Leda (L.50), in possession of the king, was noted by Antonio Mini in a letter to Michelangelo as being large and heavy. It also has the novelty—”uno aonovato”—of a small picture set within it. These features suggest the kind of settings, although in stucco, that Rosso would design for his pictures at Fontainebleau.

Between October and December 1531 Rosso was paid by the king “pour ung model d’une sépulture” (L.49), a lost project that must have been for the burial of someone closely connected to Francis I. It may have been partly architectural in character, and it may be supposed that it contained sculpture. The document that mentions this model for a tomb also records sums that were paid “pour le louage dune maison loude A Paris pour la demourance de me Roux, painctre” and “pour l’amesnagement de lad. maison.” Rosso had now been living in Paris for a year and it was probably there that his activity was centered. But, as has been indicated, he probably had, in this period, already become familiar with the château at Fontainebleau, had painted a picture for it, and possibly designed a grand staircase for the Cour Ovale. As will be shown, he also began to plan the decoration of parts of the château although the execution of any decoration there probably did not begin until mid-1532 at the earliest.

There are several French works by Rosso the style of which, close to that of his late Italian works and to the Mars and Venus, seem to have been done before he began his decorative schemes at Fontainebleau. The style of these early French works suggests, however, that they may be slightly later than the Judith known from Boyvin’s engraving.

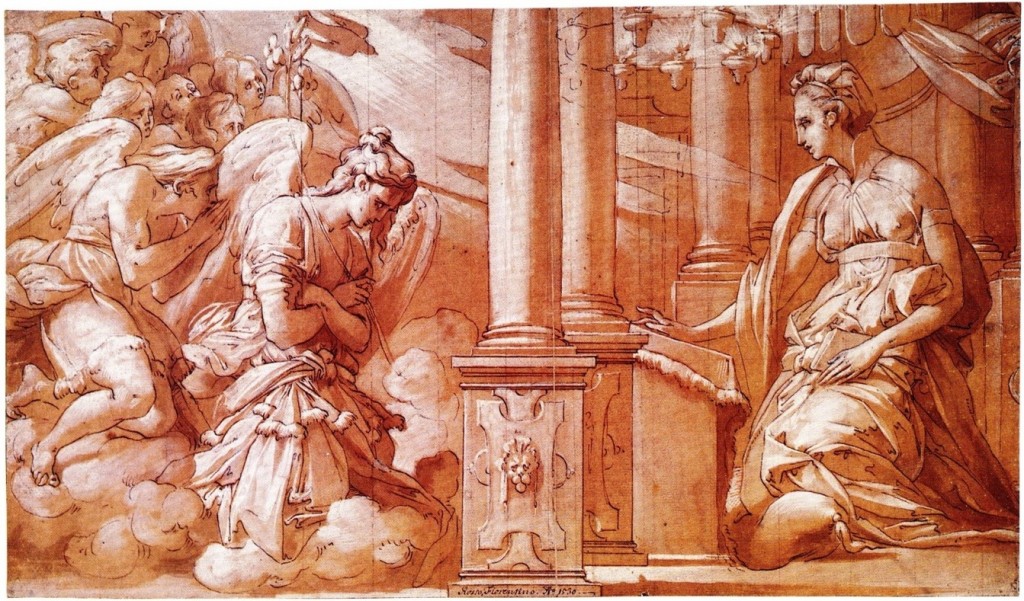

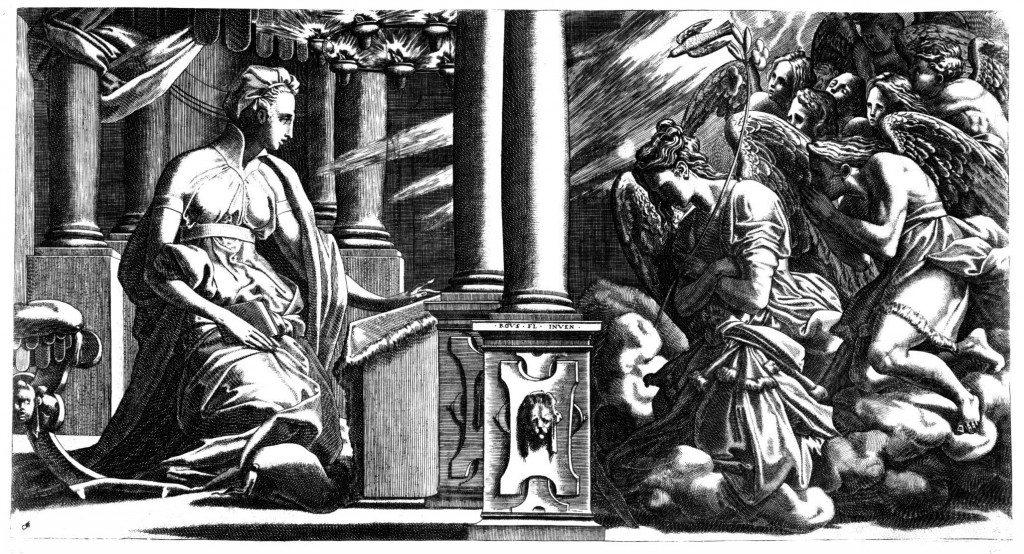

In its elegance, in the plastic wholeness of its forms, and in its spatial clarity the Annunciation drawing in the Albertina [CENTER LARGE Fig.D.43] is similar to the Judith. The eloquence and dramatic focus of the Annunciation also relate it to the Judith but also differentiate it from the slightly earlier Mars and Venus. In all these aspects it is almost identical in style to the St. Peter and St. Paul.

The decorative aspects of the Annunciation are largely confined to the rich folds of the figures’ drapery. Compared with Judith’s coiffure and the coiffures of the women in the Mars and Venus, the Virgin’s headdress is simple in keeping, one might say, with her traditional modesty and with the general gravity of the Annunciation as Rosso envisioned it. The media of the Albertina drawing—pen and ink, brown washes, and white highlighting applied to light brown paper—are fundamentally the same as those of the Mars and Venus drawing. And yet, the handling of them is significantly different. Though in both an overall penumbral tonality is created by the dark paper and the dark washes, the highlights in the earlier drawing are small and scattered while in the Annunciation they are broader and more fluid. Forms in the latter consequently appear denser and are revealed by a light that gives the impression of moving continuously through the half-dark scene. The courtly splendor of the scene, with its spacious columned hall, its baldachin and flaming oil lamps, and elaborate chair—only fully visible in the print—give weight and authority to its drama. The royal splendor of the scene is not merely the refinement of the Mars and Venus or even that of the decorative elements of the Judith, but more a kind of dense richness that contributes to the seriousness of the event. No element of aloofness is felt. There is a recollection in the Annunciation of the loveliness of Rosso’s Marriage of the Virgin and yet realized here after Rosso’s Roman activity and his last years in Italy. In its use of architecture there is some precedent in the St. Roch drawings, in the Sabines composition made in Rome, and in the Adoration of the Magi designed for Alfani in Pereugia. But, no earlier depiction of architecture in a picture by Rosso creates such a grand and noble environment. Only the portrait in Naples gives a comparable sense of the completeness of the surroundings of the scene. In the figures of Gabriel and the angel behind him, there seems revived something of the Michelangelesque robustness and complexity of pose of the figures in the early study in Rome for the Christ in Glory (Fig.D.29) and the, approximately contemporary, Allegory of the Immaculate Conception (Fig.D.30), in a German private collection. However, the solemnity of the Annunciation carries some of the reserve of the figures in the altarpiece in Città di Castello (Fig.P.20a).

But as the Annunciation can in many ways be recognized to revive several of the most inventive and vigorous aspects of Rosso’s Roman and post-Roman art, it also presents them in what must be seen as quite a different manner. It is remarkable, coming after the Mars and Venus and after the two Michelangelesque drawings mentioned above, how impressive the Annunciation is in its conception without the pretension of the Venetian drawing that Rosso made for Francis I. Gabriel and the other angels, accompanied by the dove of the Holy Spirit in a radiance that outshines the light from the chandelier hanging above the Virgin, have come not only to announce the incarnation, but to worship the Virgin who kneels on a cushion before a lectern. The postures and gestures of reverence are experienced as felt, with the lion’s head on the foremost column base suggesting here not the Throne of Solomon—as in the Aretine drawing in Besançon (Fig.D.34)—but the House of Wisdom as symbolic of the Virgin.22 One is reminded of the late Raphael and of the tapestry cartoons with their grave figures and architectural settings. Nothing in the Annunciation specifically recalls the Holy Family and the St. Michael by Raphael that Francis I owned and yet their large and clear designs, and grandness in general, could have been inspiring to Rosso. Rosso’s grace is less pervasive than Raphael’s and the style of his Annunciation on the whole is less magnificient and less brave than that of Raphael’s pictures. If at this time he had already studied Raphael’s pictures in Francis I’s collection, then the clarity and fullness of Rosso’s composition may well have been inspired by Raphael’s example. Or should we see the style of the Annunciation more simply as an extension of the architectonic conception of the Città di Castello altarpiece with its own Michelangelesque and Raphaelesque antecedents? While, however, this drawing reflects the artistic attitudes of the Christ in Glory, it also presents a style that is less eccentric. Vasari, knowing it only from the engraving, referred to it as “una Nunziata bizarre”. But rather than bizarre, as one might characterize Rosso’s Last Supper in the Marucelliana, the Annunciation is a remarkably serene and elegant invention that reveals a new consolidation of Rosso’s artistic abilities at the court of Francis. Even more than the Judith, the Annunciation presents a new refined vigor in Rosso’s art that marks the beginning, if not the very beginning, of his activity in France.

The size of the squaring of this drawing may suggest that it was intended as a study for a rather large picture. No record of an Annunciation painting exists and Vasari’s reference to the engraving of this work does not indicate that a painting of it was, in fact, ever executed. However, although such a picture may not have been painted, the drawing itself nevertheless reveals the kind of intentions that were Rosso’s, it may be assumed, around 1531 or 1532.

????EDIT ABOVE ON THE ANNUNCIATION AND COMMENT ON ITS RELATION TO THE STYLISTICALLY IDENTICAL PETER AND PAUL.

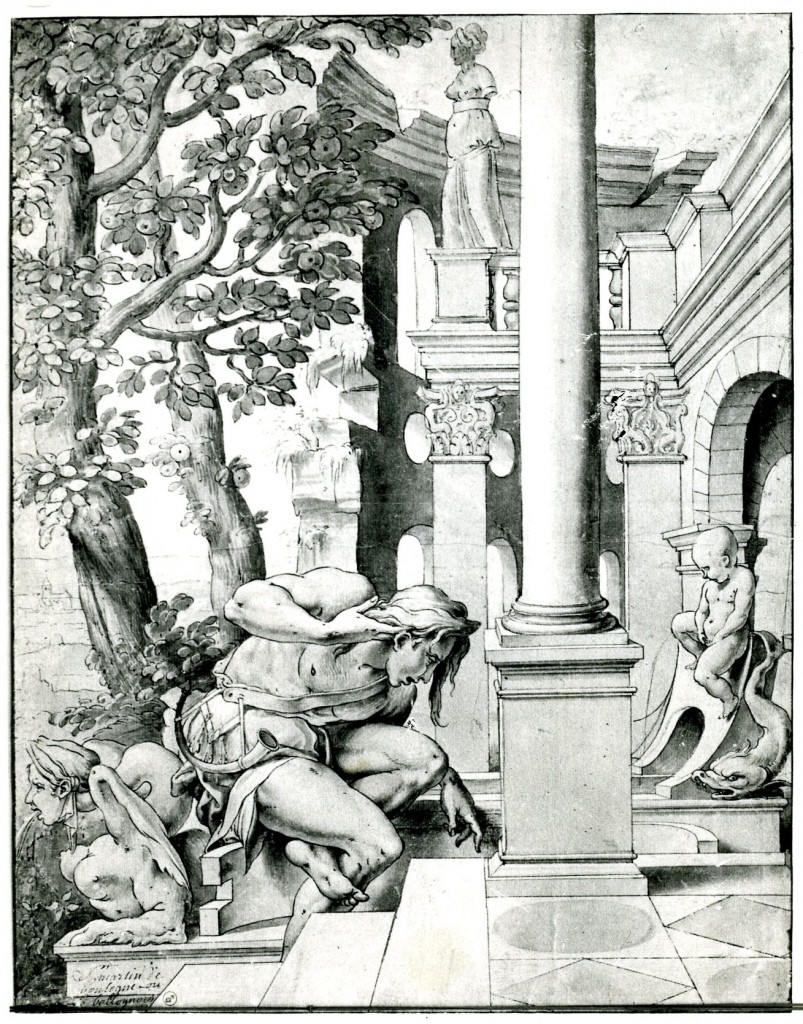

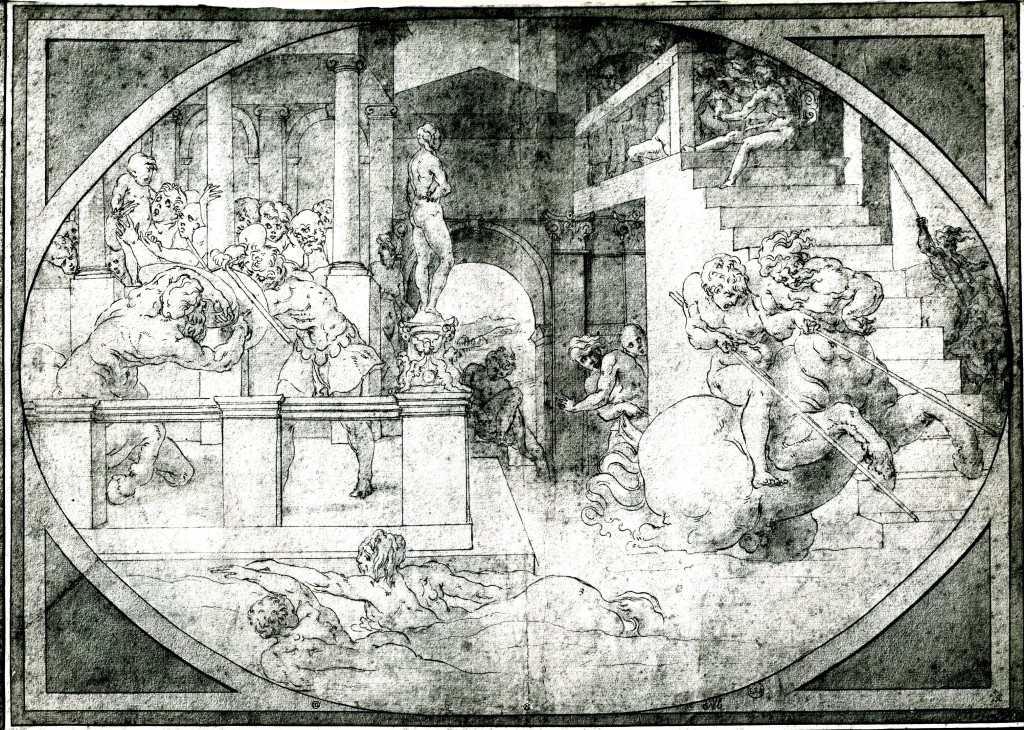

The very same style is shown in a good copy of a lost drawing of Narcissus in Turin. The composition is also known from a very small engraving of 1569 by Étienne Delaune, in the same direction and inscribed to Rosso, that shows slightly more of the composition at the left and especially at the right and bottom where the drawing has been cut. As in the Annunciation, there is a large architectural setting with two unfluted columns on high bases (the right one visible only in the print), behind which is a portico placed before the ruins of a large two story structure. There are also several pieces of sculpture in the scene: a partially draped but armless female figure on a pier above the portico at the top and center of the scene, a harpy spurting water from its mouth into a basin of water at the lower left, and a fountain composed of a peeing putto, a dolphin, and a pool at the right side in the middle distance of the scene. In addition, there are two sculptured capitals, one with satyrs, the other with griffins. At the left are two fruit-bearing trees and a landscape with a small building that, with its spire, looks somewhat like a church.23 Narcissus is shown almost nude with a hunting horn decorated with feathers hanging at his side. He is seated at the edge of the semi-circular pool, which is in front of the pool with the peeing putto, and immediately behind the bases of the unfluted columns. The surface of the water of the pool at which Narcissus looks is not visible. Seated with his left foot hooked behind his right knee he holds his hair back with his right hand as he gazes down at his reflection that is not seen by us. His left hand gestures toward the invisible face he sees on the surface of the water. Although Narcissus is the largest single element in the scene, the setting that surrounds him occupies more of the composition than in any earlier work by Rosso. Only the setting of the contemporary Annunciation in the Albertina bears comparison with it, and that of the Narcissus is more complex in a setting of new architecture and ruins and more elaborated with sculpture. It is imagined with the myth that is represented. There is a special concern with space and perspective resembling that of the Roman St. Roch drawings. But, space is even a greater issue in the Narcissus, as can be most fully appreciated in Delaune’s print where the entire foreground perspective is preserved and where the youth’s placement in the middle ground can clearly be seen.

The Narcissus is no mere illustration of the story in Ovid’s Metamorphosis (3:402–514);24 for Rosso’s setting has nothing to do with the secluded woodland pool describe there. In the drawing, and in the print, water settings are emphasized with three constructed pools and two fountains but no visible water. The putto as a fountain appears in Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of 1499 [Fig.Peeing Fountain].25 The harpy as a fountain is unusual, and possibly novel at the time.26 The putto may be an allusion to the sexual aspect of the story, and it is possible that the dolphin at his side is meant to suggest Venus, born from the sea.27 A similar boy, but standing and not represented as a fountain, is found at the side of the Death of Adonis in the Gallery of Francis I where its meaning seems to be sexual in relation to Venus’ love for Adonis [Fig.Peeing Boy]. Or, the putto may have been intended as a detail to lighten, with implications of fertility and good fortune,28 the narration of Narcissus’ intense and threatening passion. The harpy in the Narcissus may be related to one of the functions of harpies in antiquity which was the abduction of the souls of the dead.29 Perhaps there is an allusion to the unfortunate aspects of the Narcissus legend, the young man’s death as the result of his pride and self-love. The satyrs that decorate one of the capitals in the background could refer to sexual behavior, while the griffins on the other capital may be there as symbols of Nemesis or death.30

Whether all elements of the image have a clearly defined meaning is open to question, including the fruit trees at the left which could be a commentary on Narcissus’ abundant endowments, or, by contrast, on the lack of issue that the homoerotic aspect of the story implies. What can be recognized as the meaning of the ruined architecture in relation to the newer building in the foreground, which, nevertheless, is decorated with a broken, armless statue? Is the dolphin on the fountain of the peeing boy there merely because it is aquatic? However, to whatever extent one may be inclined to find meaningful the individual details that appear in the setting of Rosso’s Narcissus, many of them lead one to interpret the image in the same way as one does the scenes that decorate the Gallery of Francis I. If done in 1531 or 1532 it is likely that the Narcissus is the earliest work by Rosso that shows so copious an arrangement of meaningful effects.

This correspondence with the decoration of the gallery and the setting of the Narcissus, so different from Ovid’s description of the site of the legend, makes one wonder if this composition was intended for Francis I’s château at Fontainebleau. The emphasis on water beyond what is required by the story suggests the origin of the name of the site of the château as presented by the scene of the Nymph of Fontainebleau planned for the Gallery of Francis 1.31 Furthermore, Narcissus as hunter, clearly defined by the horn that hangs from the strap across his body, is not a major aspect of the legend. Yet in the context of the château, which had its beginnings as a hunting lodge, this detail assumes significance. One is also struck by the appearance in Rosso’s scene of fruit trees and landscape with the architecture of civilized life. The new architecture placed before the ruin also suggests the renewal of that civilized life in a pastoral setting. It cannot be proven that Rosso’s composition was intended for this site, but it has to be recognized that the Narcissus introduces, at a time when Rosso was beginning to concentrate his activity on the decorations for the château at Fontainebleau, a kind of artistic conception that he would employ there.

If the Narcissus was intended for a painting, the inscription from Ovid (3:466)—”What I desire is with me, Abundance has made me poor”—that accompanies the scene in Delaune’s print would, most probably, not have appeared with Rosso’s original image.32 Without this line the image need not be so specifically tied to Ovid’s narrative, and the setting of Rosso’s scene suggests a separation from that text. Nevertheless, one is struck by the richness of the scene, filled with nature at the left and with architecture and sculpture elsewhere, an abundance (Alberti’s copia) CHECK THIS of effects that must be taken into account as one contemplates the meaning of the Narcissus legend as depicted here.33 In this abundance we do not see what Narcissus is looking at, his own image. Instead, we concentrate on his act of seeing and are meant to imagine what he sees; a recollection of what occurs in the Roman Apollo in a Niche also with its Ovid inscription. Thus, it is possible that another theme of the picture may be the invention of painting as indicated by Alberti in his De pictura, in which he wrote, with reference to Narcissus as the inventor of painting: “What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool” (“fontis” in Latin, “fonte” in Italian).34 This idea may stem from the opening line of Philostratus’ description of a painting of Narcissus in his Imagines: “The pool paints Narcissus, and the painting represents both the pool and the whole story of Narcissus.”35 We do not see the illusion that Narcissus sees but rather, through the art of painting—Rosso’s image—the youth seeing what is hidden from us, the reflection that Rosso might well have recognized could not be effectively represented.36 It might, thus, be possible to interpret Rosso’s Narcissus both as a picture of the invention of painting and, at the same time, as a complex telling of Narcissus’ story with its implications of pride, self-love, and death. Both aspects of this subject could have been meant for a painting that was to be placed in the château at Fontainebleau, where the art of painting was, through Rosso, to have a new beginning in France under the patronage of Francis I.

The emotion and action in Rosso’s red and black chalk St. Jerome in the Louvre has some of the dramatic impulse of the figure of St. Paul in the engraved St. Peter and St. Paul. However, the ample space around St. Jerome relates this drawing more to the Narcissus in Turin and to the Annunciation in the Albertina. But in all of these works, evidence of an ambitious grandness of purpose and of emotional intensity is, in spite of the degree of successful realization, guarded in its effects. The large forms and movement of St. Jerome are reduced in their formal and emotional impact by the attention that is given to detail, by the regularity and dryness or granularity of its draftsmanship, and by the pictorial effects created by the use of red and black chalks.37 His anatomy is precisely rendered and the drapery placed around, but not covering, his body is piled up on the ground before him and is carefully turned and folded. The nude saint reminds one, to some extent, of the bare backed man in the Volterra Deposition and his drapery recalls some of the drapery passages in that altarpiece. Certain aspects of the anatomy and drapery in Rosso’s Madonna and Child with Four Saints of around 1519 [Fig.D.4] may also be called to mind. A degree of the feeling of these early works seems again to exert itself in the St. Jerome, as in the St. Peter and St. Paul. These similarities give some indication, in what appear to be his early French works, of concerns that were Rosso’s at his first maturity. And yet, the visionary implications of the St. Jerome are undercut by a certain literalness that is far from the brave abstraction of Rosso’s pictures of 1521, which also differentiates it from the red chalk Madonna delta Misericordia of 1529 with its fluctuating emotional fervor and its subtle pictorial cohesion of form and chiaroscuro.

There is no documentary evidence that the Judith, the Annunciation, the Narcissus, the St. Peter and St. Paul, and the St. Jerome were done between late 1530 and, as it has here been assumed, around 1532. Furthermore, the possibility exists that other works, different in style, were created within the same period. Nevertheless, these five works may represent a particular mode of expression of a certain moment of Rosso’s career rather than an intermittently recurrent mode throughout his years of activity in France. If this is true, what is remarkable about these works is the consistency of their style that is unusual for any group of works earlier in his career. There is not an absolute sameness about these works; for the requirements of each subject have inspired Rosso’s imagination to respond especially to it. One has the sense, however, that the necessary differences that do exist are contained within a set of artistic terms that Rosso has recognized as forming, now, the proper currency of his expression. Though impetuosity of feeling and individuality of detail are not eliminated, they are strongly controlled. One is reminded of the restraint of the Dei Altarpiece and of the Marriage of the Virgin following the passionate expression of the Volterra Deposition and the obsessive severity of the Villamagna altarpiece. Yet, the control in the early French works is more complete than in the Florentine pictures of 1522 and 1523. As it appears in all five of these works, this control also seems now more stable. The surety of style of these French works suggests a new confidence as well as a new sobriety. As painter to the king of France and, with a position in which he could work without the expectation of adverse criticism, Rosso’s art in these early years in France may well reflect his new sense of security. It could also reflect his appreciation of the nature of his new responsibilities at the French court that may have led him, however, to limit too free an expression of his extraordinary imagination.

DOCUMENTS OF ROSSO LIFE 1531–1532

Several documents of late 1531 and 1532 attest to the stabilization of Rosso’s life in France after a period of activity of less than two years. Around 1o December 1531, Antonio Mini, on his way to France, wrote to Michelangelo from Piacenza, saying, “Credo, sechondo the ciertti Fiorentini the venchano di chortte [de’] Re esi m’àno detto, ch’e’ Rosso dipintore è diventantto gra’maestro di danari a d’attre provisione ch’e’ Re à dantto loro” (DOC.17). Writing on 23 December to Michelangelo from Lyons he mentioned “Rosso dipintore” in the same vein: “…e’ Rosso àne avunto gra[n]disima provisione,…” (DOC. 18). On 2 January 1532, he wrote again to Michelangelo from Lyons saying that he had heard from many who had seen Rosso that he “chavan[c]ha [c]hon tanti servidori e [c]ho [c]hovertine di setta a usso d’isingniore grande” (DOC. 19). Very soon, then, after his arrival in France, Rosso had exchanged the “miseria e povertà” that were his in Italy, according to Vasari, for a life of luxury as a painter to the king of France. Francis I paid Rosso very well—a salary of 1400 livres a year and additional payment for his works of art—and further rewarded him with letters patents granted in May 1532 (DOC. 24). These state, first of all, that the king had called Rosso into his service and that the privileges he was being given were “Pour l’excellante et grant industrie qu’il a en cest art.” In addition to the rights of ownership of real and moveable property and of inheritance, Rosso was granted the privilege of holding ecclesiastical dignities and benefices, both secular and regular, and of obtaining from them up to one thousand scudoes of revenue a year. Only three months later, on 14 August 1532, he was made a canon of Sainte-Chapelle, a position he held until the end of his life (DOC. 25).

None of the French works thus far considered probably date later than 1533. None can be shown to belong to any large decorative project. The subject and details of the Narcissus do, however, suggest a possible connection with the château at Fontainebleau, the decoration of which was Rosso’s major occupation in France. Furthermore, the decorative motifs of the St. Peter and St. Paul are closely related to some of those employed by Rosso at Fontainebleau. In other words, it is very possible that in the first years of his activity in France, Rosso was considering schemes of decoration to be executed at Francis I’s favorite residence, the enlargement of which had begun in 1528. It has already been suggested that he was engaged on architectural designs there in the second half of 1531.

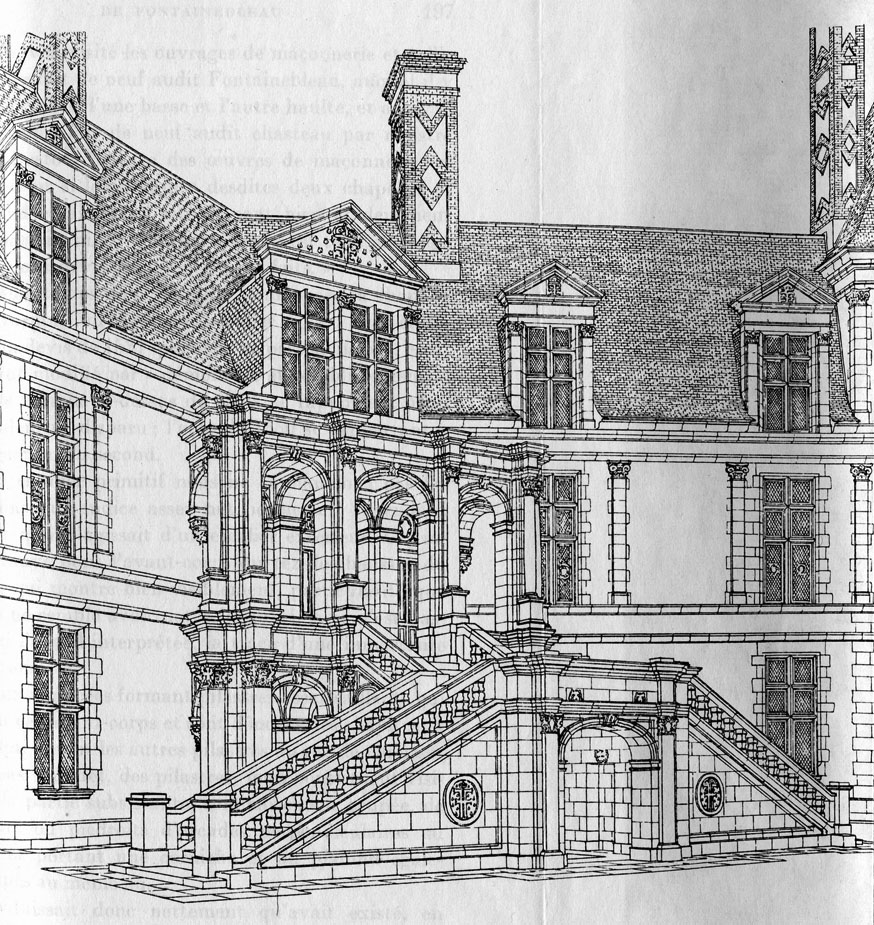

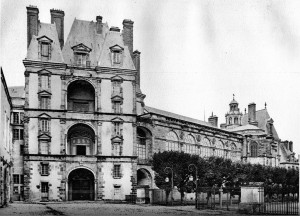

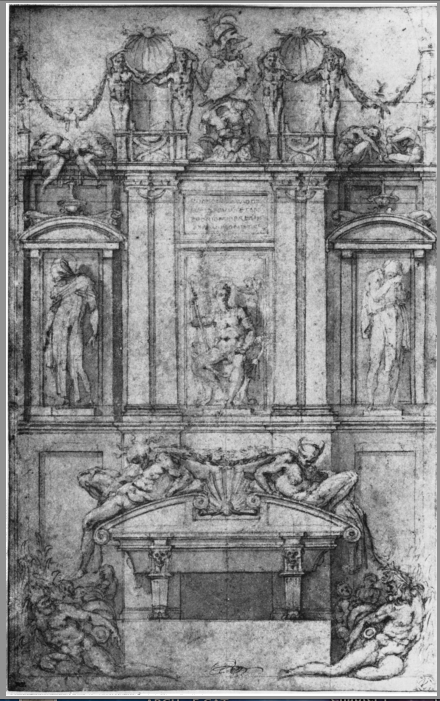

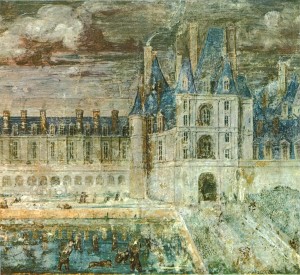

FONTAINEBLEAU, ARCHITECTURE

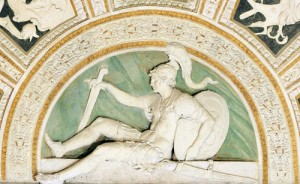

It was proposed by Chastel, that Rosso may have been responsible for the design of the grand escalier that Gilles Le Breton was directed to build in the Cour Ovale at Fontainebleau on 5 August 1531 (A.2). The staircase was destroyed and only its portico rebuilt shortly after Rosso’s death. But its plan, known from the excavations made by Bray, is of such a character to suggest that someone other that Breton was the designer of it. Blunt found Chastel’s theory persuasive, and Guillaume thought that the portico and staircase were probably designed by Rosso. Hence, as a possibility, at least, Rosso’s authorship of the conception of this staircase and portico must be seriously considered. Adding to what we know of Rosso’s architectural ideas from his Aretine Design for a Chapel (D.37) and Design for an Altar (D.38), the staircase may give some further support to Vasari’s claim that, “Nell’architettura [Rosso] fu eccellentissimo e straordinario.”38 It may also give support to Vasari’s remark made early in his account of Rosso’s career in France, that Francis I, “lo fece capo generale supra tutte le fabriche” at Fontainebleau, although this may be an exaggeration.39 He is presented as a painter and an as an architect in the frame of his portrait in the 1568 edition of Vasari’s Lives [Fig.Portrait].

As reconstructed in Bray’s elevation drawing based upon the excavated remains, the staircase projected from the north side of the Cour Ovale near to the place of the presently rebuilt large entrance portico that leads to an interior stairway. In 1531, the north side of the Cour Ovale turned at a wide angle toward the southeast, just where the new exterior staircase was to be placed. The new staircase partly masked this angle at the same time that the shallow depression formed by it provided the space from which the staircase projected with some sense of being framed by the building behind it. Furthermore, the spatial richness of the projecting forms of the new structure gave a dramatic focus to the conglomerate of buildings that surrounded the Cour Ovale, especially as seen from the windows of the Small Gallery which was probably built about this time directly across from the staircase. Its possible decoration by Rosso shortly thereafter will be considered below.

The staircase was formed of a forward part composed of two flights of stairs rising across the front of the building and ending in a platform joining the two flights at the top. Beneath this platform was an archway that led into the ground floor of the building. From the platform, a less steep single flight of stairs rose, like a bridge, to the level of the first floor. Against the building was set a shallow portico, open by a single arch projected at each end and by three arches across the front. This portico, which was narrower than the length of the two flights of steps and the platform in front of it, was placed upon a similar one at ground level. At the lower level, arches were probably flanked by pilasters and square piers with capitals carrying entablatures. The upper level may have had full round columns in front of the piers of the arches. Without protruding too far into the courtyard, the staircase provided clear access to the building and its royal apartments on two levels. As an escalier d’apparat and an immense construction dressée théâtricalment, quoting Babelon, it presented a grand setting for exits and arrivals with ample space provided on it and within the portico for spectators at ceremonial occasions.40 Such ceremonies could also have been watched from the windows of the Small Gallery across the way.

Although the form of the staircase with two straight ramps leading to a platform from which a third is directed to the first floor of the building has precedents in France, Chastel pointed out that its design at Fontainebleau shows two important innovations. First of all, its forward element is more geometrically conceived than was that of any earlier example of this kind of staircase in France. And second, the entire structure gave the appearance of a triumphal arch now on two levels and not simply as a feature of a portal at entrance level. This elevation of the triumphal arch motif was new in France and does not seem to have precedent in Italy. Although the details of the elevation seen in Bray’s drawing are to some extent conjectural, they do follow out the implications of the plan that almost certainly required the regular distribution of piers, pilasters, columns, capitals, and entablatures that are shown in the reconstruction. These present a degree of plasticity that is quite unlike the flatness of Gilles Le Breton’s Porte Dorée that was constructed about the same time. In other respects, too, this entrance, with its slightly asymmetrical design and its strips that link the windows vertically, is unlike the staircase. In spite of the design of the central arch under the platform that resembles the central arches of the Gilles Le Breton’s Porte Dorée, it is very probable that the grand escalier was not designed by him even if he was responsible for its construction. Rosso’s authorship of it may not be absolutely provable, but it is very likely. Its design has details in common with his spatially complex Design for an Altar, in the British Museum, which seems to have been done just before Rosso went to France.

CHAPEL OF SAINT SATURNIN

CHAPELLE HAUTE DU ROI

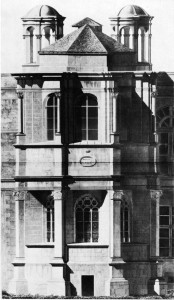

Beginning in 1531, the portico and staircase in the Cour Ovale are mentioned in the same documents with the chapel that was built across from them. This was actually two chapels, the Chapel of Saint Saturnin and the superimposed Chapelle Haute du Roi (A.4).

The similarity of exterior details of the two level apse—the designs of capitals, in particular—to details of the portico has long been recognized. Chastel thought the chapels, portico, and staircase may have been related to a monumental scheme, and Babelon actually attributed the plan of the Chapel of Saint Saturnin to Rosso.41

Until more is discovered about the design and construction of these chapels the extent to which they can be associated with Rosso will remain unclear. Certainly, details of the apse point to a relationship with the portico and staircase, and the few dates related to the construction, if not completion, of the chapels before 1540, make possible Rosso’s participation in their design. While a contract of 5 August 1531, calls for a chapel at ground level, the building soon became designed as two chapels one on top of the other; the Chapelle Haute du Roi being on the same level as the Small Gallery, from which it could probably be entered. This private chapel for the king could have been a substitute for the chapel that in 1528 was planned for the east end of the Gallery of Francis I and which would almost certainly have been the king’s private chapel. It was eliminated when the plan of the gallery was enlarged. But the design of the two-level apse of the chapels shows that the decision to build two chapels was made before construction had begun, for the lower and upper parts of that apse appear to be parts of a single design.

The plasticity and Italianate architectural vocabulary of the exterior of the apse of the chapels is in most respects far removed from the planar style of Le Breton whose Porte Dorée is just the other side of the Salle de Bal.

The original forms of the interior of the chapels, as seen through subsequent changes to them, also indicate Italian origins. The robustness of the lower side vaults of both chapels and the upper columns of the upper chapel, have a decidedly Roman aspect. The vaults in the Chapel of Saint Saturnin, resembling the arch under the platform of the staircase, might remind one of the central arches of the Porte Dorée. But the upper vaults of the Chapelle Haute and the fenestration of both chapels have proportions that are less Italianate, and suggest an accommodation of the conceptions of the chapels to French gothic architecture that is not apparent in the entirely secular staircase and portico. It is in these gothic aspects that Rosso’s design of the chapels seems compromised. Such may well have been the case with Le Breton very possibly having his part in their conceptions, as he would have as director of their construction.

CENTERED [Fig.Sylveste,Pavilion]

CENTERED Fig.Sylvestre,Grotte

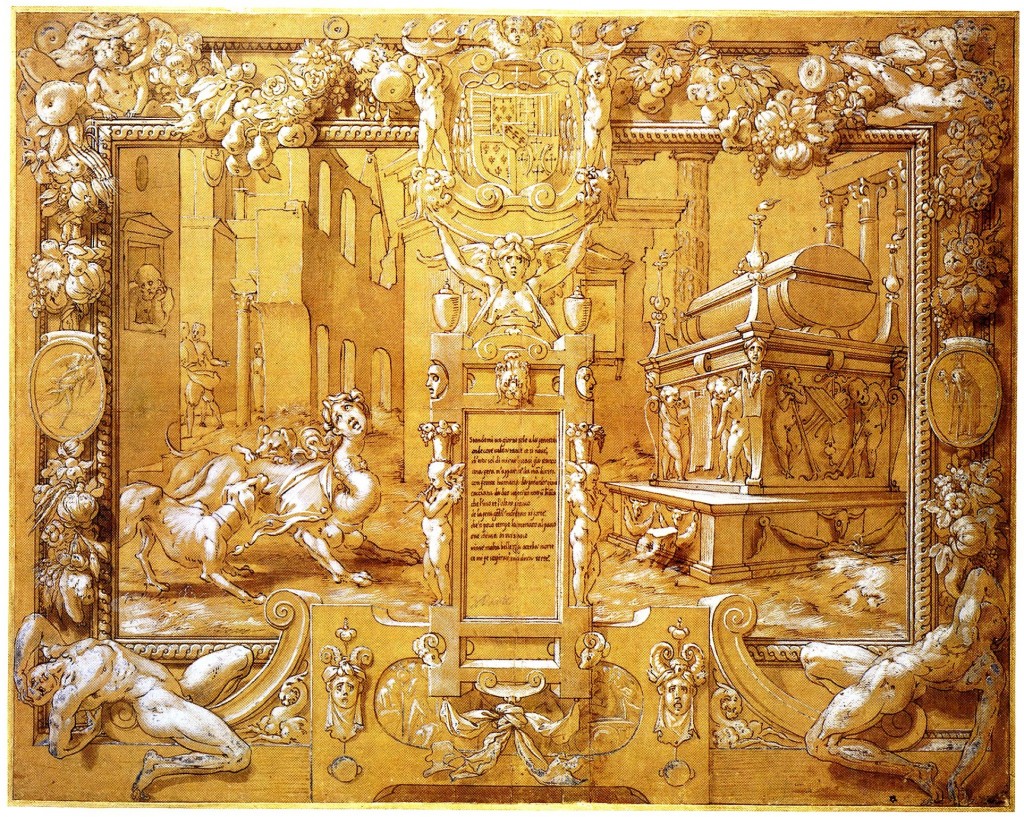

THE PAVILION OF POMONA

There are no sixteenth-century documents related to the lost Pavilion of Pomona (L.39). Its existence, in fact, was not even recorded until the following century, and it was partially described then, and again in the eighteenth century. Visually, however, it is a remarkably well-recorded work, preserved by several drawings and prints that together give us a good, if not complete, indication of what was planned for it and what was actually executed. One of the two frescoes that decorated this pavilion was by Primaticcio, the other was by Rosso who also designed the stucco ornament that surrounded both paintings. As Primaticcio’s scene was clearly an early work by him, it is unlikely that his picture was an addition to a project left incomplete by Rosso. Consequently, the appearance of these two paintings by Rosso and Primaticcio in a single artistic complex marks a planned collaborative effort, and the only such planned collaboration in the decorative schemes at Fontainebleau where works by both were to be seen in the same space. This fact strongly suggests that the Pavilion of Pomona was done very shortly after Primaticcio’s arrival in France when he might well, for a moment at least, have had to work under Rosso’s direction. It was very likely Primaticcio who executed Rosso’s stucco designs for this pavilion, bringing to realization probably for the first time in France, and at Fontainebleau, that kind of association of sculpture and painting that was to become the hallmark of the decorative schemes at Francis I’s château. The pavilion could have been done as early as 1532, in which case, the request, mentioned above, to Lazare de Baïf for “couleurs à fres” could, partly, at least, have been for the execution of the frescoes of this pavilion. It is likely that it was not done after the middle of 1533 when Primaticcio was occupied with the decoration of the Chambre du Roi.

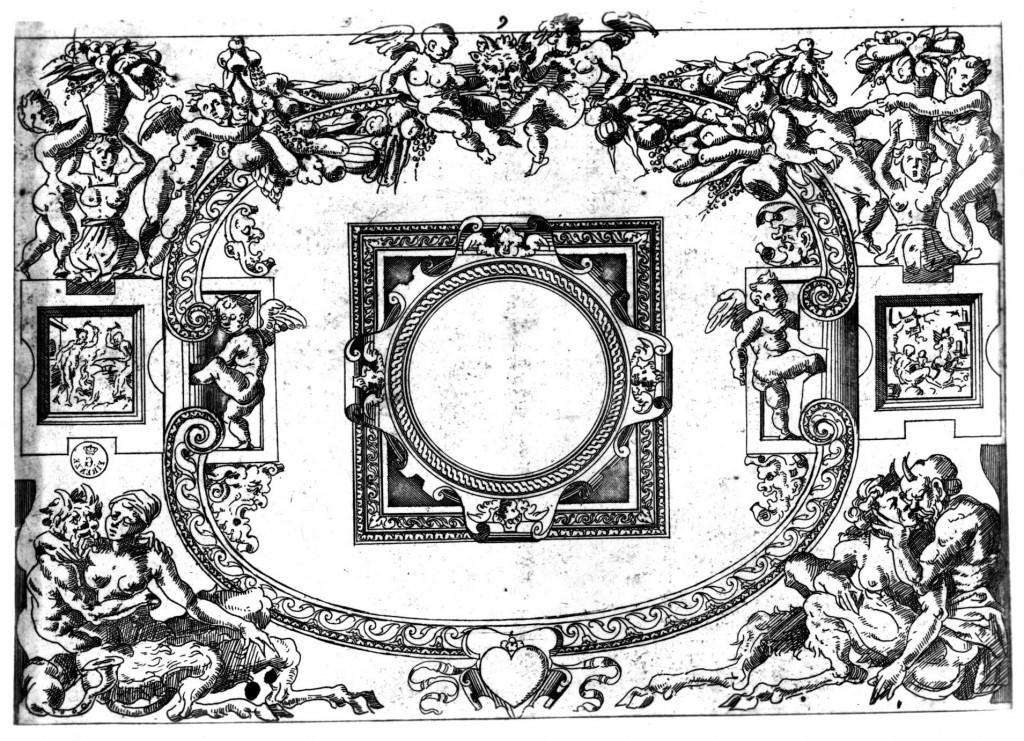

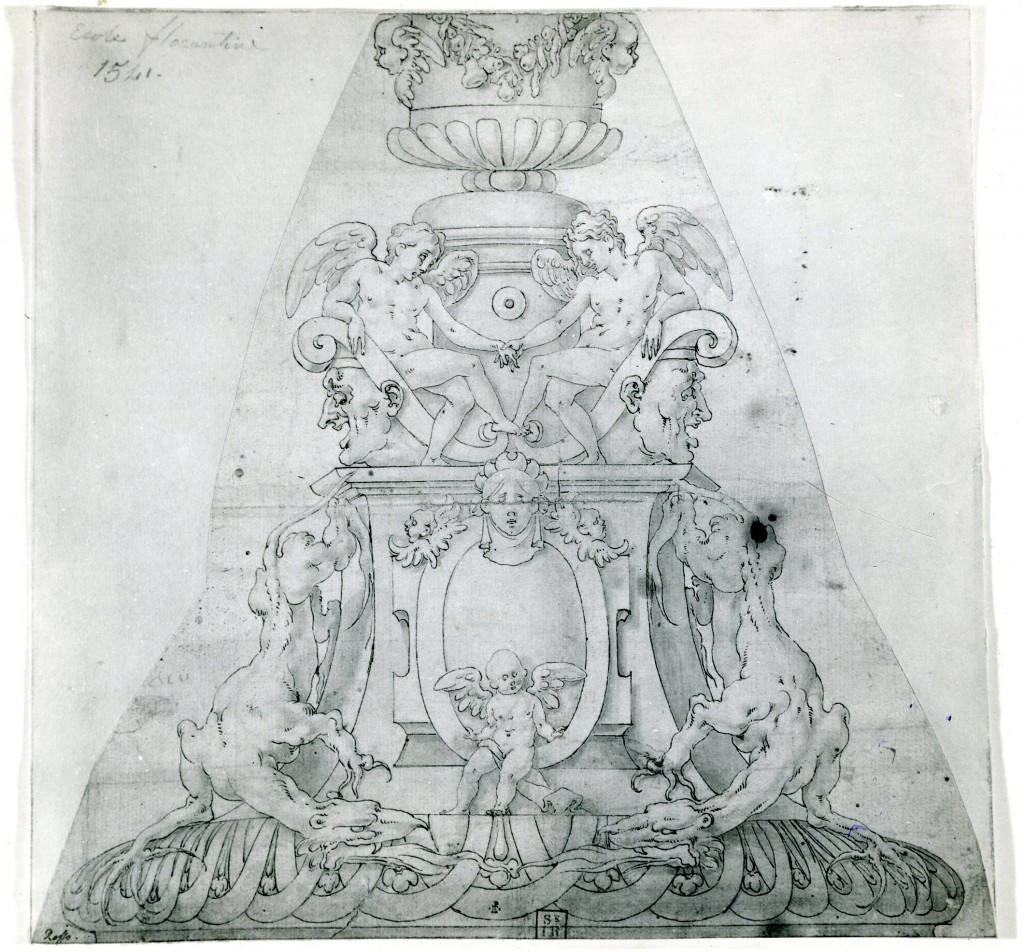

The Pavilion of Pomona was a small square structure, open on two sides, set into the northwest corner of the walls that enclosed the large garden to the south of the Cour de Cheval Blanc. In 1731, Guilbert described it as follows: “Le corps bâtiment qu l’on voit dans l‘angle septentrional de ce Jardin [des Pins] prés de la galerie d’Ulysse, porte le nom de Vertumne et de Pomone, parce que les amours de ce dieu at de cette déesse sont representés en deux tableaux à fresque du dessin de Saint-Martin, sous un pavillon carré soutenu par quatre pilastres de gresserie d’ordre composite, couronné de frises corniches et chapiteaux aux chiffres de François Ier, qui l’a fait construire et orner de plusieurs têtes de divers animaux et chiens de chasse d’une parfaite beauté.” The two paintings—which Dan thought were by Rosso, Guilbert thought were by Primaticcio, and Mariette gave to both—were on the inner faces of the walls of the pavilion. Rosso’s was on the west wall and Primaticcio’s on the north. Opposite to them the pavilion was open in the direction of the two broad paths that flanked the adjoining garden. The stucco ornament originally planned by Rosso for the pavilion is preserved in an etching by Fantuzzi that shows an oval center, the same shape indicated for the pictures by copies of a lost drawing by Rosso and by drawings given to Primaticcio.

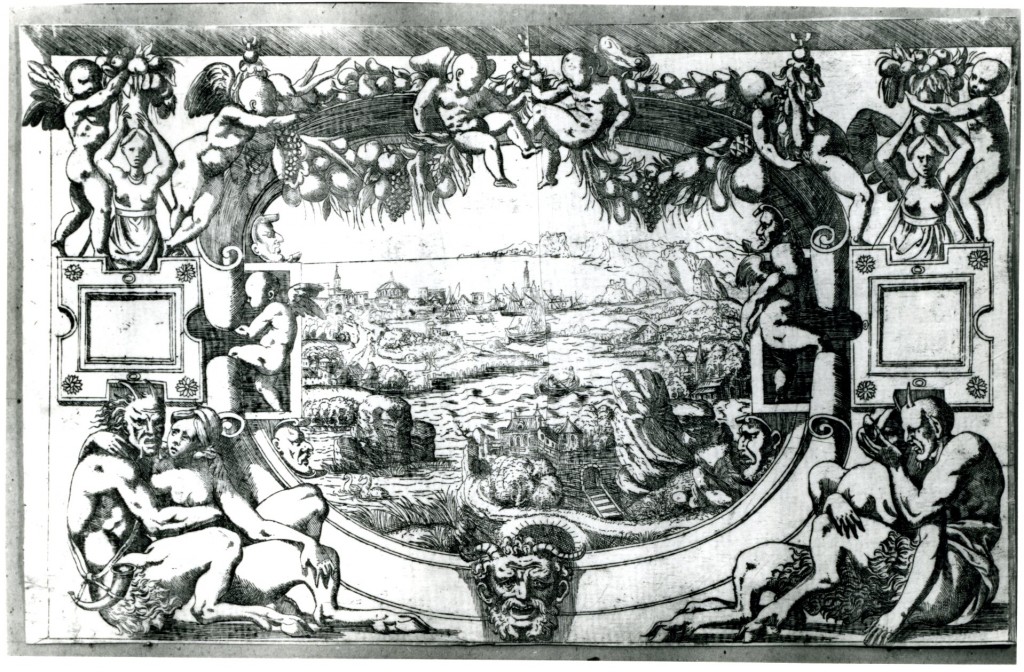

Although oval frescoes with stucco frames containing small scenes within them, as indicated by the blank rectangles at left and right in Fantuzzi’z etching, may not actually have been executed in the pavilion, the combination of large frescoed pictures and large stucco sculpture framing them seems to have made its first appearance here in France in what was planned for the pavilion.42 The possible sources of this remarkable arrangement require some consideration. A drawing in the Louvre [Fig.Louvre, 3497] that has been related to Primaticcio’s decoration of the Chambre du Roi shows a project of stucco herms and moldings framing painted scenes.43 The drawing has been attributed to Primaticcio but its former attribution to Giulio Romano cannot be entirely disregarded. Even if the sheet could be proved beyond any question to be by Primaticcio its basic conception appears due to Giulio. It has been suggested, on the one hand, that the drawing was actually sent by Giulio to Fontainebleau to aid Primaticcio one would suppose, and on the other, that it is a copy by Primaticcio of this drawing sent from Mantua.44 As it served, irrespective of its authorship, the conception of the decoration of the Chambre du Roi, it would have to have been done before 2 July 1533, by which date work had begun in that room.45 Should it date a while before this time it could also have influenced Rosso’s conception of the Pavilion of Pomona. His decorations in the Gallery of Francis I appear to reflect aspects of this drawing.

However, aside from the fact that the Louvre drawing, by Giulio or by Primaticcio, projects a scheme combining paintings with large-size stucco figures and ornament, its style bears little relation to that of Rosso’s original scheme for the Pavilion of Pomona. In the Louvre drawing the pictures are square and are framed with relatively flat classical moldings. The stucco figures simply flank the paintings, one on either side, with trophies piled up between the center two. In its regular alternating order of square pictures and standing figures this scheme reflects its ultimate origins in Raphael’s art, such as the decoration of the basamento of the Stanza d’Eliodoro. Rosso’s first scheme for the Pavilion of Pomona included oval pictures, the shape also of the lost oil pictures first executed for the Gallery of Francis I. It might be appropriate to add to the list of oval scenes the small ones that decorate the entablature of the bed in Rosso’s Mars and Venus drawing. Although oval pictures of the size of those planned for this pavilion seem to be altogether unprecedented, small oval and painted medallions are an integral feature, together with painted grotesques and stucco ornament, of such earlier Roman decorative schemes as those of the Villa Madama and the Sala dei Pontefici in the Vatican. However, there the small oval scenes are placed in a field of slender painted and stucco decorative motifs by which they are lightly held in place. The decorative motifs including figures belong to the world of ornament and are, also because of their small size, not immediately related to the pictures they surround, even when they are thematically related. The stucco sculpture designed by Rosso was large; the figures of satyrs and putti were as big as, and even bigger than, the figures in the painted central scenes. This created, along with the large flat and curled ornament of the framing stuccoes, a density of design that was quite unlike the light and airy decoration in Rome. This density is also an aspect of the Louvre drawing related to the Chambre du Roi, but there the regular spacing and parallel alignment of the parts of the decorative scheme still give a discreet value to each element. While there is a certain amount of overlapping of parts in the Louvre drawing, this is, to a great extent, related to the creation of plausible natural relationships between the various parts. In the Pavilion of Pomona the oval areas containing the central pictures were to be broken into by rectangular stucco niches at both sides, by the wings and limbs of the putti placed in them, and by four masks set above and below these niches. From above, the ovals stucco garlands, as well as the feet of two putti sitting on these swags, were meant to hang down over the pictures. At the bottom of the ovals it seems that the curling horn of a stucco mask and the knee of one satyr were to overlap the painted areas. The independent value of the framing stuccoes and the framed paintings, as appears in the Giulio-Primaticcio drawing, was lessened by Rosso to create a more fused decorative ensemble.

One could say lessened, however, only if Rosso’s scheme is recognized as an extraordinary transformation of what is given in the Louvre drawing. Except for the two small half-length women with baskets on their heads that flank the central oval in Fantuzzi’s etching and which might be considered related to the herms in the Louvre drawing, Rosso’s scheme does not appear seriously connected to the Raphaelesque mode of that drawing. It is likely that Rosso found much more compatible with his own sensibility Michelangelo’s decorative schemes of the Sistine Ceiling and even possibly his early designs for the wall-tombs of the Medici Chapel known from two copies in the Louvre. [Fig.SEE USE OF BOTH ELSEWHERE ]46

The relationships of Rosso’s scheme of decoration to Michelangelo’s art are not so explicit as to give a Michelangelesque cast of form to the conception of the Pavilion of Pomona. It is, rather, the close association of painted scenes, and the projected figures and architecture around them, that suggests a bay of the Sistine Ceiling. Furthermore, the rather free relationship of sculptured figures to the more architectural decorative motifs of Rosso’s design recalls the composition of the Medici tombs as seen in the Louvre drawings. It is possible that the medallion flanked by putti at the top of the drawing for the Magnifici tombs (Louvre 838) was intended to receive a painting, or a pictorial relief. There may also have been intended frescoes in the upper storey of the Medici Chapel, the projected inclusion of which, if not their actual compositions, Rosso may have known something about before he left Italy. There is also the possibility that Rosso was even more immediately stimulated by actual drawings by Michelangelo that Antonio Mini may have brought to France in the spring of 1532.47 Certainly the kind of density of Michelangelo’s conceptions has more to do with Rosso’s than does the relationship of parts found in the Giulio-Primaticcio drawing in the Louvre. It should also be recalled that in 1532 Rosso seems to have designed a large frame for Michelangelo’s Leda that Mini brought to France—a frame that had a small painting set within it (L.50).

The use of stucco and its use on the large scale that was planned, possibly for the first time by Rosso, for the Pavilion of Pomona may have had a precedent in Giulio’s decorations at the Palazzo del Te. Surrounding the Garden of the Grotto the upper walls have large stucco herms flanking arches, half of the background walls of which have stucco scenes in high, if not full, relief; the alternating walls had frescoed scenes that are now lost [Fig. Garden of Grotto]. The date of this decoration is not known but it is possible that it was being executed just at the time that Rosso left for France,48 although it has also been dated later.49 Rosso might have seen it himself, or plans for it, if he visited Mantua on his way to France. In its conception this scheme of decoration is not far removed from that of the Giulio-Primaticcio drawing in the Louvre. As outdoor decoration, bringing to mind in this respect what some earlier festival decorations may have looked like, the combination of stuccoes and paintings of the loggia at Mantua could, most appropriately, have been recalled by Rosso when he was faced with the task of decorating the open Pavilion of Pomona in the corner of a garden at Fontainebleau. There were also large and high stucco reliefs of Mars and Neptune in the Sala degli Stucchi in the Palazzo del Te as well as large stucco reliefs surrounding them [CENTER PAIR Fig.Stucchi & Fig.Mars].

Vasari claimed that these stuccoes were by Primaticcio and hence they had to have been done before his departure early in 1532, and were possibly done before March 1530.50 Rosso could, with even more probability, have seen these works and could also have met the stuccoer that Vasari said executed them. When later it crossed Rosso’s mind that stucco should also be part of the decorative schemes at Fontainebleau it could then have occurred to him to ask Francis I to call Primaticcio into his service.

It is not known if Rosso designed the structure of the pavilion. Guilbert’s description of its exterior does not suggest any details that would necessarily point to Rosso’s invention. Sylvestre Israel’s (ADD DATE AND REF TO L.39) etched distant view of it shows a square building of the simplest kind, but, except for the square corner supports and capitals, it shows none of the other details mentioned by Guilbert. Nor does it show any elements that might indicate Rosso as the architect of the pavilion. The etching depicts a square painting on the west wall of the pavilion surrounded by a plain border without any indication of stucco sculpture, and here Israel’s view may require us to recognize that the oval frescoes and stucco frames that were planned were not executed. His depiction of this small structure is likely correct in showing some kind of paneling, in stone or stucco beneath a square painting, as well as a long bench supported by brackets attached to the wall under it. The north side would have had the same paneling and probably another bench as well. The idea of a permanent garden pavilion made of cut stone and decorated with pictures may go back to antiquity, as the subjects of the decoration of the Pavilion of Pomona certainly do.51

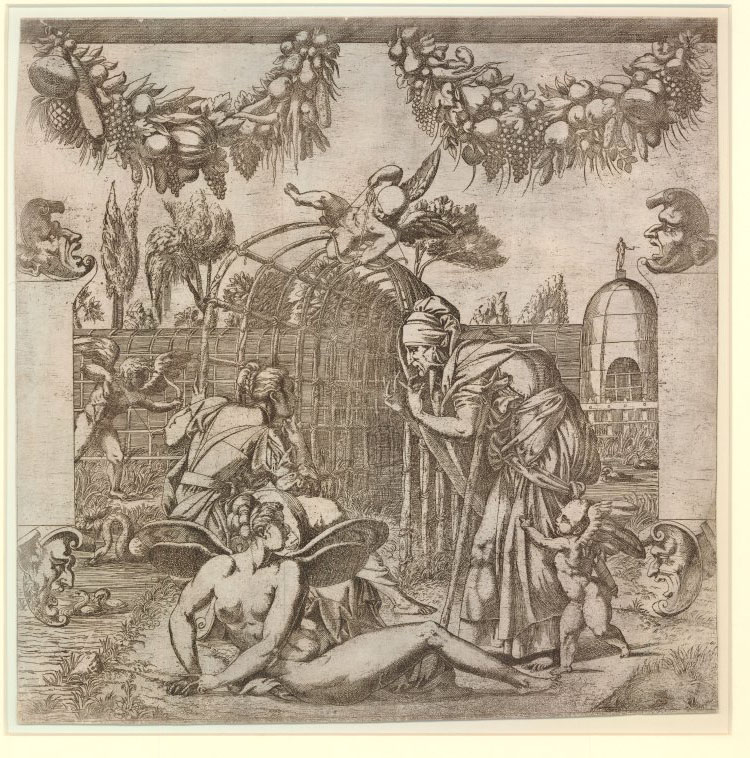

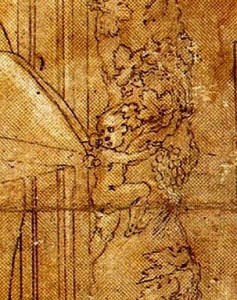

The identical stucco frames above the paneling were designed by Rosso, according to Mariette, as was the fresco on the west wall; the other painting, on the north wall, was by Primaticcio, and its composition shows that it was done in correspondence with Rosso’s. The theme of the decoration was derived from Ovid’s account in his Metamorphoses of the story of Vertumnus’ love for Pomona.52 In Rosso’s picture, known from copies of a lost drawing and from an etching in reverse by Fantuzzi, Vertumnus, as an old woman, approaches the opulently dressed Pomona while three amorini encourage their romance, one by gently shoving Vertumnus and the others by shooting arrows. There is a small body of water behind Pomona and on its bank in the foreground reclines a nude and winged nymph who may suggest a personification of Fontainebleau.

The subject of Primaticcio’s fresco, known most completely from a reversed print by Léon Davent, is not quite so clearly dependent on Ovid’s story, although the picture contained a herm of that nameless god whose single member/ Is pointed as a sickle when it rises/ And frightens certain people when they see it53, although no fright is shown here.