Giovanbaptista et Romolo di Jacopo di Ghuasparre, called Rosso Fiorentino because of his abundant red hair, was born in Florence on Saturday, 8 March 1494, at the eighteenth hour after dawn in the “popolo di Santo Michele Bisdomini” [Visdomini].1 (While of little significance so early in our history, it may well be later of some importance to note that Francis I, who called Rosso to France in 1530, was born the same year, on 12 September.) It has been suggested, or at times merely implied, that Rosso was the pupil of Andrea del Sarto.2 Some evidence supports this possibility, but it is only partially satisfying as proof of a circumstance that is nowhere documented or remarked upon in an early source. In 1568, Vasari reported Bronzino’s recollection that Pontormo told him about Rosso’s having worked with him on the now lost predella of Sarto’s San Gallo Annunciation. This would have been around 1512 when both Pontormo, born 26 May 1494,3 and Rosso were eighteen years old. A short while later Rosso began to work at SS. Annunziata, the atrium of which, since 1510, had become the center of Andrea del Sarto’s activity. There is also the evidence of Andrea’s style on Rosso’s earliest surviving work.

Nevertheless, in neither the 1550 nor the 1568 edition of the Vite does Vasari say that Rosso was Sarto’s pupil. Instead, he tells us that “con pochi maestri volle stare all’arte, avendo egli una certa sua opinione contraria alle maniere di quegli;…”4 But with which “maestri” had he not chosen to stay for long? More than one master is indicated, but none is named. Bronzino’s recollection was not introduced into Vasari’s “Life” of Rosso but was given merely as a remark in his 1568 “Life” of Pontormo. The young Vasari had known Rosso between March 1528 and April 1529, just before he went to France, and the 1550 edition of the Vite had been begun only about a decade and a half after Rosso’s departure from Italy. Vasari mentions four artists with whom Pontormo studied one after the other: Leonardo, Albertinelli, Piero di Cosimo, and Sarto.5 The same kind of list might have been given for Rosso if the manner of his artistic education had been similar. But what seems to be suggested by the absence of such information is that Rosso’s relation to his “few masters” was different from Pontormo’s to the artists with whom he studied, and that Vasari’s information about Rosso’s unsettled artistic education is substantially correct. It would indicate both Rosso’s “contrary opinion” toward the various styles of the masters from whom he learned his art, and the different character of his education that resulted from his contrariness.

Vasari’s understanding of Rosso’s state of mind as a young artist came from their association in Arezzo in 1528 and 1529, which arose from Rosso having seen and praised a small painting of three half-length saints, St. Agatha, St. Rocco, and St. Sebastian, by Vasari in the Servite church of San Piero d’Arezzo. Their relationship must have become a close friendship by the time that Rosso made a drawing of the Resurrection for Vasari’s use in the execution of an altarpiece for Lorenzo Gamurrini following the plague of 1528 (L.22). Although this was well before Vasari began thinking of writing the Vite, his memory still recalled what Rosso had said about the few masters from whom he learned to paint but with whom he also did not wish to stay for long because of “a certain opinion of his own that was contrary to their manners of working.”

If we can assume that Vasari here accurately records what Rosso, now age thirty-four and thirty-five, told him, then we should also see this comment as that of an experienced painter who already had had by then an extensive and complex career where several works had aspects that were seen as contrary to what was expected of him.

From the time of Rosso’s birth in 1494 to around 1512, when he may have worked with Pontormo on the lost predella to Sarto’s San Gallo Annunciation, little is known of Rosso’s life as an artist. But of his family and its possible origins the documents published by Waldman in 2000 provide interesting details.6 This period of Rosso’s early life was entirely, but for its first seven months, within Republican Florence, from the expulsion of the Medici on 9 November 1494, until their return on 1 September 1512, when Rosso was eighteen years old. He is first noted as a “pictore” in a document of 8 August 1510 (DOC.1c), where he is named as a witness to the distribution of property among the members of the Davanzati family. He was sixteen and living in the parish of S. Maria del Fiore.

A document of 18 January 1513 (DOC.1d), records his acting for himself and his two clerical brothers in acknowledging the payment of a debt to his father, Jacopo di Guasparre di Giovanni, by his nephew, Domenico da Civitella, who had accepted this debt five years earlier on 21 November 1508. Six days later, on 27 November, Rosso’s father renounced his office of “fanti del rotellino” on the household staff (the famiglia) of the Florentine Signoria, which he had held since at least 1495, in favor of this same nephew. While it was legal to pass on these positions of the famiglia, they were not to be sold, the rule “more honored in the breach than in the observance” (to quote Waldman). In their vague language, this is what these documents indicate was taking place between Jacopo di Guasparre and his nephew. As Waldman has reported, these positions in the famiglia were generally held by non-Florentines. Jacopo filled the office of the Specchio and would have been responsible for the ballots of communal offices and for making sure no tax delinquent was elected. These positions also included pensions, the last balance of Jacopo’s having been paid to his family a month after his death on 10 November 1512. The record of this payment gives his name as “Jacobo de Civitella,” indicating, like his nephew’s name, that the family came from Civitella, identified by Waldman as Civitella del Vescovo near Arezzo in the territory that had belonged to Florence for over a century. Upon the death of his father, Rosso would have become head of his family, to which his later appointments of procurators to handle matters in Florence may be related.

Jacopo might have passed on his position to one of his sons. But in November 1508 Rosso was only fourteen years old and probably working to become a painter. His two brothers may have decided by then to become clergymen and would soon become friars in two of the most prestigious churches in Florence. All of them were successful in their ambitions to have lives beyond the servant class into which they were born. One might wonder if their father’s position gave him contacts that helped his sons, as when the sixteen year old Rosso was a witness to a legal affair within the prestigious Davanzati family.

Of the two brothers, Fra’ Costantino di Iacopo belonged to the Dominican conventual house of S. Maria Novella and was an ordained priest by 1527 and a member of the consiglio of the church. The other brother, Fra’ Filippo Maria, was a member of the Servite order at SS. Annunziata, who eventually became the convent’s procurator and lived to at least 1532. Furthermore, in 1515 he was commissioned to restore ex-votos in the church, around the same time that Rosso was making wax effigies for the Annunziata, suggesting the role that his brother may have had in his employment at this church. Rosso’s earliest independent work, for which he was paid on the 19 and 30 of September 1513, was for two coats-of-arms of Fra’ Aurelio d’Arezzo, the General of the Servites, in his room at the Annunziata (L.7).

On 10 September 1513, Rosso was paid for polychroming a large wax statue of Duke Giuliano de’Medici by Baccio da Montelupo at the same church (L.6). Five days before he seems to have been paid for helping Andrea di Cosimo Feltrini paint, at the same church, the coats-of-arms of Pope Leo X and his brother Giuliano. On 20 September 1515, he painted another coat-of-arms of the pope at the Annunziata (L.9) in preparation for his entry into Florence on 15 November. For these festivities, he created a triumphal arch dedicated to Hope (L.12) and the decoration of the Custom Officer’s station on the route of Pope Leo’s departure from the city (L.13). None of these works was actually commissioned by the Medici, nor was Rosso ever thereafter employed by them, as their artistic interests were served rather by Pontormo, and then also by his pupil, Bronzino. Perhaps it should be wondered if Rosso, through his family, was known not to favor the return of the Medici, a factor in the loss of their patronage.

If Rosso continued to reside in the parish of S. Maria del Fiore, he may have known Pontormo before they worked for Sarto as Pontormo lived until about then in the nearby via de’ Servi.7 In any case, by 1512, or thereabouts, he knew Pontormo at Sarto’s studio in the buildings known as the Sapienza, not far away between SS. Annunziata and Piazza San Marco. There, Rosso would have met Franciabigio, Jacopo Sansovino, Tribolo, Solosmeo, and the older Rustici, whom he would almost certainly know again in France.8

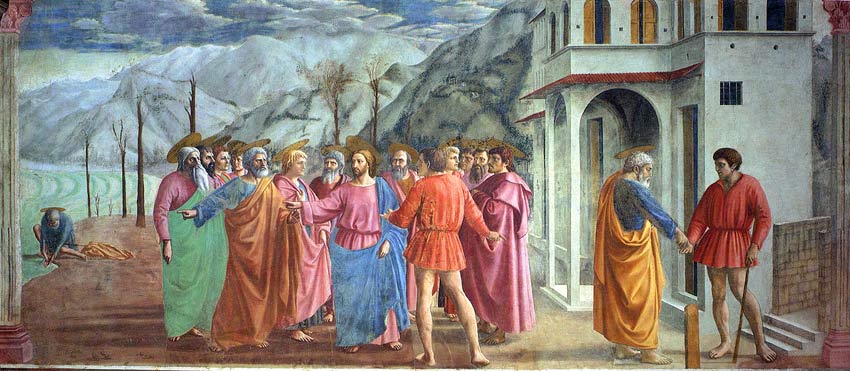

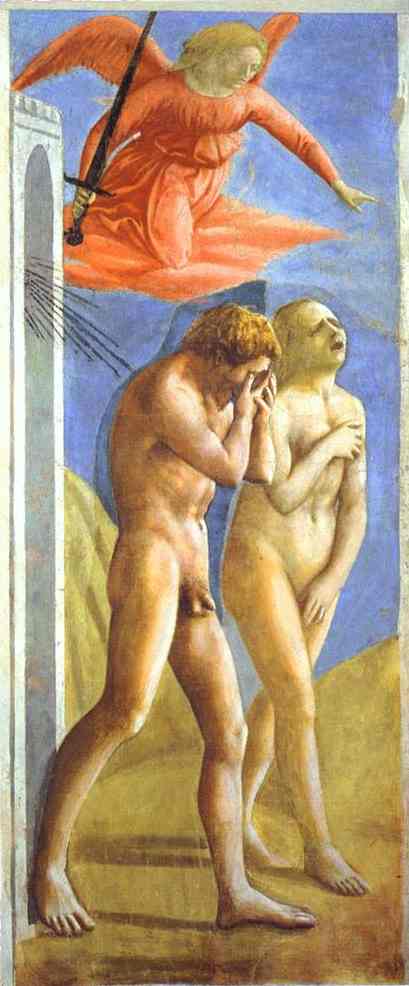

At eighteen Rosso was, like Pontormo, a painter of some training and recognized ability or else it is unlikely he would have been allowed to work with Pontormo on the predella for Sarto’s altarpiece. Where that early training in the materials and basic technique of painting took place has not been discovered, but, as suggested by Waldman and Franklin, it could have been from a minor and well-established decorative painter such as Giovanni Battista del Piccino, whose family’s shop was behind the Duomo (see DOC.2a). Only one reference to Rosso’s education can possibly be placed earlier than his arrival at the Sapienza: Vasari’s comment in his “Life” of Masaccio that Rosso drew from the frescoes in the Carmine.9 None of Rosso’s drawings made from these paintings has been found, but the references to his having drawn from these pictures may still have meaning for us. Given, according to Vasari, the number of young artists who studied them, it was clearly not an uncommon activity. By the early sixteenth century in Florence it was an established practice of artistic education and a means whereby Florentine artists shared and maintained the traditional values of their art. It need not, however, lessen the value of Rosso having studied Masaccio’s frescoes that everyone else did also. Instead, it confirms the common Florentine ground of his art that reveals itself until the very end of his career in France. The Unity of the State in the Gallery of Francis I is dependent upon Masaccio’s Tribute Money, while in Italy the figure of St. John in the Volterra Deposition can be traced back to the Adam of the Carmine Expulsion of Adam and Eve. The early Assumption at SS. Annunziata also gives evidence of Rosso’s study of Masaccio’s paintings, about which more will be said later.

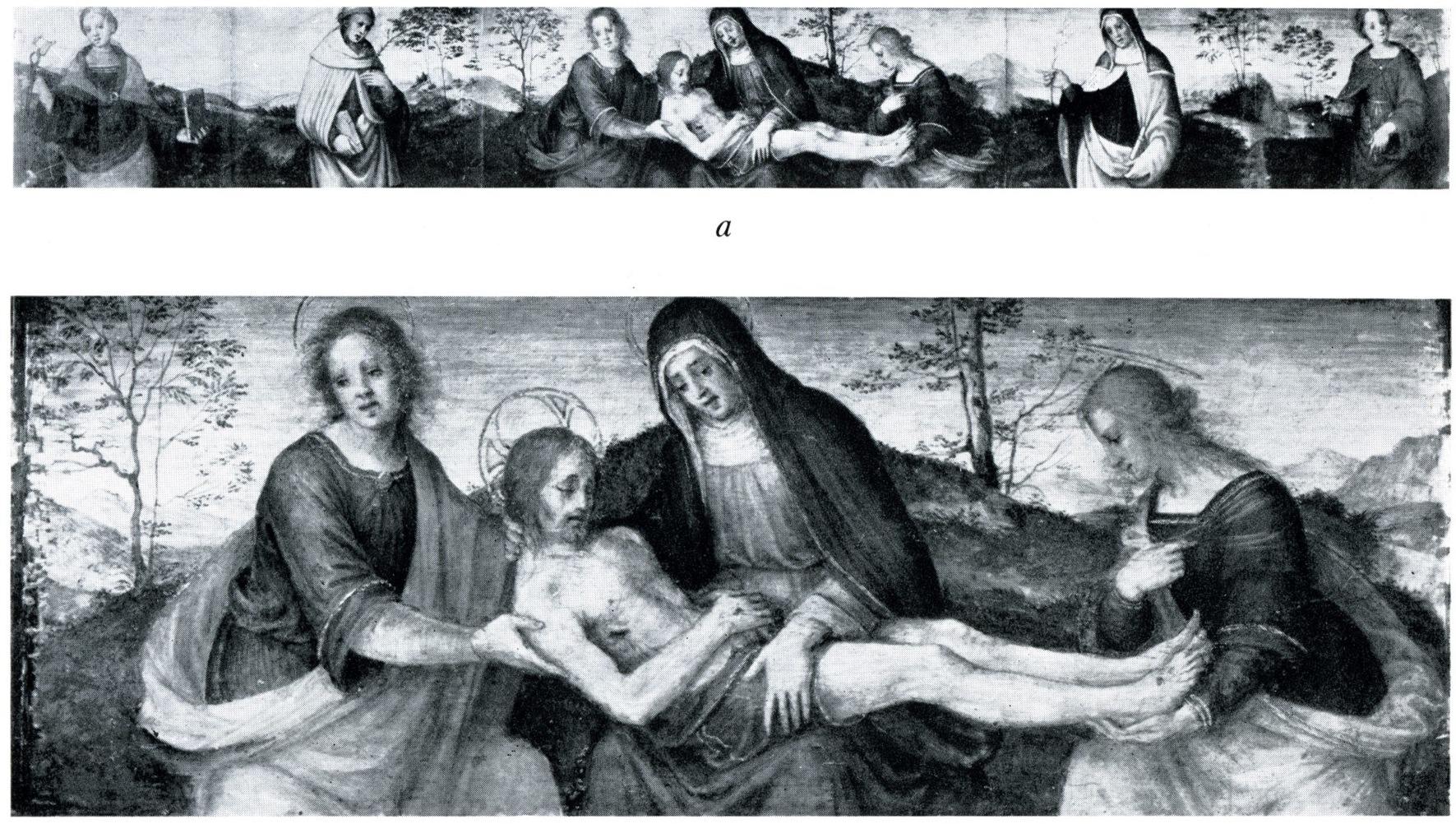

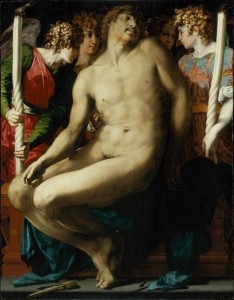

Nothing survives of the predella that Sarto gave to Pontormo to paint around 1512 for the San Gallo Annunciation. Vasari may give a full description when he writes of its three small panels as showing: “un Cristo morto con due angioletti, che gli fanno lume con due torce e lo piangono: e dalle bande in due tondi, due Profeti.” Bronzino, who had heard it from Pontormo himself, reported that Rosso worked on the predella (L.2). The number of pictures that Vasari mentions would not have formed a very long predella, unless they were widely spaced. The only surviving predella by Sarto, painted around 1507–1508 for an unknown altarpiece and showing a wide Pietà in the center, flanked by two almost square panels of individual saints, is similar to the format of the later lost predella with, however, only a single saint in a “tondo,” not a square shaped panel, at the sides of the Pietà.10 By this time the predella itself had become a minimal feature of an altarpiece, sometimes missing entirely, as indicated here by the smaller number of panels of the lost predella than of the earlier surviving one.

While it would seem unlikely that the two artists worked together on any one of these small panels, there is no way of knowing that this would not have been the case. According to Vasari, the Dead Christ Lit by Two Small Angels Holding Torches of Sarto’s predella would seem to have been painted by Pontormo, known already as Andrea’s discepolo. With angels holding two torches to light Christ, this small scene could have served Rosso as a precedent for his own large Dead Christ created over a decade later in Rome, and now in Boston. Might this suggest that Rosso had something to do with this small panel, the memory of which lingered with him for so long thereafter?

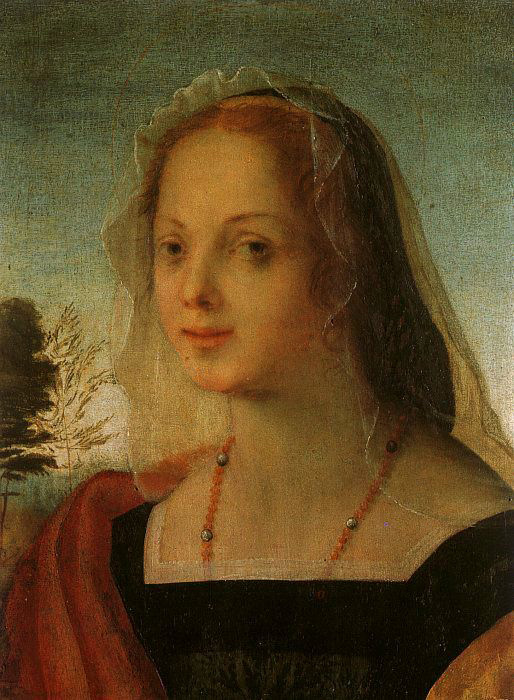

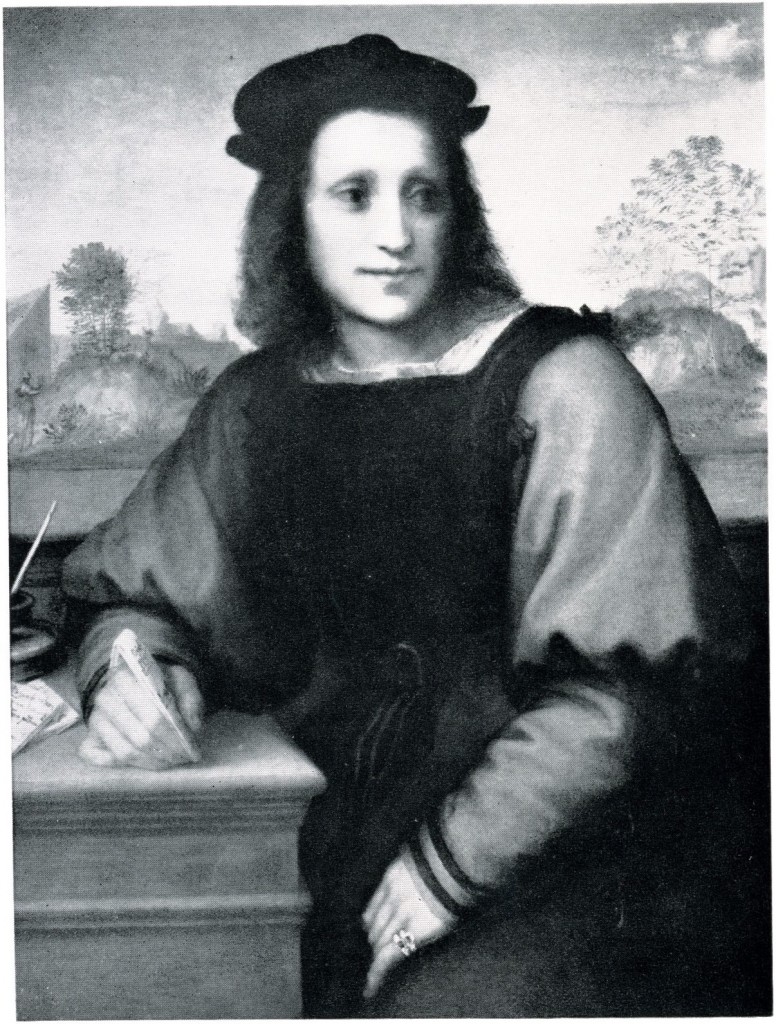

With the loss of this predella, Rosso’s earliest work from around 1512 may instead be studied from his Portrait of a Young Woman as Mary Magdalen, in the Uffizi (P.1). The effect of this work, which would be Rosso’s earliest surviving painting, is undeniably Sartesque and shows an immediate acquaintance with Andrea’s work just prior to his San Gallo Annunciation (Fig.Sarto, Annunciation). The response of the young Rosso to Sarto’s art appears sympathetic and even modestly imitative of it. The image has a gentle and even a somewhat evanescent quality that suggests Sarto’s male portrait at Alnwick Castle of around 1511 or 1512.11 But the slight Leonardesque smile of Rosso’s young woman is somewhat more like the expression of the comparably thinly painted heads in Andrea’s Tobias Altar of around 1511.12 To the extent that the repainted lower part of Rosso’s portrait follows the original, a certain breadth in the shapes of her dress and in the bold folds of drapery coming over her right shoulder may be due to the example of Sarto’s more vigorous Procession of the Magi of 1511.13 However, no later works by him would need to have been seen to encourage, in a young artist of eighteen, the creation of the style of this small portrait.

The picture need not be subjected to an overextended stylistic analysis or evaluation in too singular a search for an understanding of the beginnings of Rosso’s art. The style of this modest portrait certainly does not show any opposition to Sarto’s, nor is there any obvious exposition of an “opinione contraria” that Vasari gives as Rosso’s own thought about the beginnings of his art, whatever Vasari himself may have meant by this phrase. The halo and the remains of a gray oval jar that the young woman holds identify her with Mary Magdalen. (Fig.P.1c) These details could simply refer to her name, Mary Magdalen, or Maddalena, or Magdalena, even to a particular young woman named Magdalena for whom Rosso was a witness to the appointment of her husband, a Florentine goldsmith, as her guardian or mundualdus (see DOC.1e).

It is possible that the Portrait of a Young Woman could, with its relationship to the Magdalen, indicate her status as a young woman about to enter a convent, where she could have assumed the identity and name of this saint. Her coral necklace, a talisman against evil, contains four pearls, possibly suggesting the four Evangelists and their Gospels. But these details that indicate the Magdalen may instead join the sitter’s beauty to the virtues of this famously beautiful saint who renounced a life dependent on her physical allure to find forgiveness and a new life in Christ.

The individuality of the style of the portrait that can be distinguished from Sarto’s, and that is not, merely an effective aspect of Rosso’s immaturity, can be seen in the young woman’s direct gaze at the spectator. Although her head is turned, and her gentle, but sharp and rather archaic smile seems to contradict the expression of her heavy-lidded eyes. The Leonardesque smile is not exploited as in Andrea’s Tobias Altar, nor so benign as in his Alnwick portrait. Rather, the Uffizi portrait seems to suggest an attempt at a more precise and yet more complex characterization, with a faint psychological analogy implied by the landscaped background recalling not only Sarto’s portrait but also Leonardo’s more atmospheric Ginevra de’Benci. Though not emphatically unusual in color, the relationships of reddish-orange, gray-green, white, and black against the light blue background of the sky strike one as distinctive, perhaps even a bit bold, although reservation is required depending on the extent of the repainting of the drapery.

One other aspect of the small portrait that might be noted is that the anatomy of the young woman is not everywhere very convincing but this is also not so very disturbing in a picture by an artist of the age that Rosso was when he painted it. What might be perceived is a certain ambivalence in regard to the role of drawing as the structural basis of the definition of the figure and, therefore, of the conception of the picture. To some extent this might be due to the Leonardesque faces and chiaroscuro that Rosso studied in Sarto’s most recent works. Still, the body of the woman is hardly structured at all in terms of form, and this is quite unlike any of Andrea’s figures. Although repainting, especially of the black of the dress, may account for a degree of flatness, what may be revealed here in the original parts is a lack of training in the traditional Florentine discipline of drawing three-dimensional form, allowing thereby an innate preference for shape and pattern to make its own effect. This is also visible in the planarity of the face. It could, then, be conjectured, on the basis of the style of this small portrait, that its author, while having learned to paint fluently in Sarto’s shop around 1512, had not undergone any intensive training there as a draughtsman of Andrea’s brilliant kind, that Rosso was, in other words, not a student of Sarto’s in the sense that might normally be meant in a Florentine shop and in the sense of an apprenticeship.14

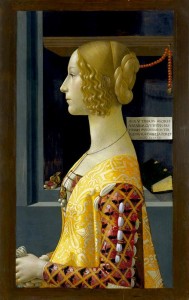

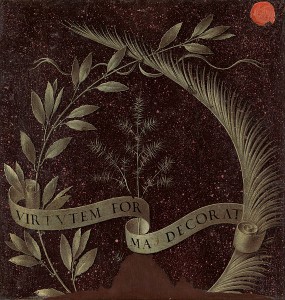

The unusual appearance of the halo and the urn in the Uffizi portrait brings us again to Rosso’s “contrary opinion.” The left edge of the panel has been cut to the extent that the inner edge of the frame obscured what remained of a hand holding an urn. This detail and the very thinly painted and barely visible gold halo that was not removed would originally have clearly identified the young woman with Saint Mary Magdalen. This particular religious identification in a portrait of a beautiful young woman may have been unknown before Rosso conceived his visual analogy around 1512. It is a conceptual change from the use of a secular inscription to propose an analogy between the beauty of the sitter and her equally important but invisible virtues in Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni of 1488 in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, with its text from the Roman poet Martial: ARS VTINAM MORES/ANIMVM QUE EFFINGERE/POSSES PVLCHRIOR IN TER/RIS NVULLATABELLA FORET (Art, if only you could portray mores and spirit, there would be no more beautiful picture on earth), and Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de’Benci of around 1479–1480 in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., with its Latin text related to Bernardo Bembo on the back of the panel: VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT (Beauty adorns virtue). It can be suggested that the religious aspect of Rosso’s family background might have brought about this image or that it was a suggestion offered by his association with “maestro Giacopo frate de’Servi” at the Annunziata, “che attendeva alle poesie.”

Rosso’s appearance in Sarto’s shop around 1512 may have been one means by which the young artist found assignments at the Servite church. Rosso’s brother, Fra’ Filippo Maria, was another. But Vasari mentions only that having painted a half-length Madonna and Child with the Head of St. John the Evangelist for “maestro Giacopo frate de’ Servi, che attendeva alle poesie,” Rosso was then persuaded by him to do the Assumption of the Virgin in the atrium of the Servite church, a fresco that was begun at the end of 1513. In 1515, only a year after its completion, Sarto was commissioned to replace it with an Assumption of his own, a circumstance that appears strange if we suppose that Rosso received his commission because he was Sarto’s pupil. Although Rosso’s fresco was never destroyed and replaced, it was again criticized by implication in 1517, when he was commissioned to do another fresco in this atrium (see under P.3 and L.10). He was clearly told in the new contract that he was to do better in the second work than he had in the first or he would not be paid. The major guarantor of the later fresco was “maestro Jachomo di Batista nostro priore,” who must in all likelihood be identified with Rosso’s earlier patron and protector, Fra Jacopo da Firenze, a scholar of theology who was also a poet, perhaps a musician who played the viola, and who was responsible for decorations in the church. Although he died in 1537, Fra Jacopo was still known to Vasari in the 1540s as having been important to Rosso’s early career.15 This second work, commissioned in 1517, was, however, never executed by Rosso or anyone else.16 The relation of these facts and references is not absolutely clear, but it is also not to be accepted that the criticism of his work was the only opinion that was had.

Still, it is not necessary to conclude from them that Rosso was Sarto’s pupil in the way that we generally understand such a relationship, or that Rosso’s activity at the Annunziata was altogether due to Andrea. In 1512 and 1513, Bandinelli and Bugiardini seem also to have contracted for frescoes at the Annunziata, and in December 1513 two others were assigned to Francesco di Lazzaro, all commissioned probably without any recourse to Sarto’s assistance.17

If Rosso worked in Sarto’s shop for a while around 1512 there is no reason to believe that he remained there for long, especially if we take seriously Vasari’s remark about the young artist not wishing to stay for long with any masters. Therefore, he may well have left Sarto’s employ by the time that he studied Michelangelo’s cartoon for the Battle of Cascina (L.3). It was probably in or around 1513 that Rosso, “nella sua giovanezza” and “ancora che giovane,” according to Vasari, drew from this cartoon when it was in the Sala del Papa at S. Maria Novella, where Rosso’s other brother, Costantino di Jacopo, was a friar. The study of this cartoon is the first specific artistic activity of Rosso’s that Vasari mentions in his “Life” of Rosso. None of the drawings that he made from this cartoon seem to have survived or to have been identified. But as in the case of his study of Masaccio’s frescoes, of which also none of Rosso’s drawings are known, it is clear from his later work, and is already evident in his very early painting for Fra Jacopo that will be discussed in its place, that he took considerable advantage of this experience. Immediately after referring to his study of Michelangelo’s cartoon, Vasari comments on Rosso’s “opinione contraria” and states that this can be seen “fuor della porta a San Pier Gattolini di Fiorenza, a Marignolle, in un tabernacolo lavorato a fresco per Piero Bartoli con un Cristo morto, dove cominciò a mostrare quanto egli desiderasse la maniera gagliarda e di grandezza più degli altri, leggiadra e maravigliosa.” This fresco would probably have been commissioned by Matteo di Cosimo Bartoli rather than his son Piero, who was born in 1500. This is the first painting of Rosso’s mentioned by Vasari and it is unfortunately lost (see L.4). A measure of Rosso’s ambitions might, however, be had from Vasari’s account of it. In any case, evidence signifies that around 1513, the possible date of this lost work, Rosso had executed a commissioned work, apparently one of some size, in fresco, and one that, in spite of its location outside Florence, was a publicly exhibited painting. As mentioned earlier, on 19 September 1513, Rosso was paid for the execution in fresco of two lost coats-of-arms in the “camera del generale” at SS. Annunziata, that is, in the room of Aurelio d’Arezzo, the General of the Order of the Servites. It might be assumed that the commission for these first works done by him at the Annunziata came about through Rosso’s association with Sarto, a conclusion, however, as has already been indicated, that is not absolutely necessary, given that Rosso’s other brother was a friar at this church. Then, according to Vasari, Rosso “Lavorò sopra la porta di San Sebastiano de’ Servi, essendo ancor sbarbato, quando Lorenzo Pucci fu da papa Leone fatto cardinale, l’arme de’ Pucci con due figure, che in quel tempo fece maravigliare gli artefici, non si aspettando di lui quello che riuscì.” This destroyed coat-of-arms, which was probably painted over the exterior door of the Pucci chapel to the right of the central portal in the atrium of SS. Annunziata, was paid for between 19 October and 14 November 1513. Rosso received over twice as much for this work than he did for the two earlier coats-of-arms in the “camera del generale.” Ten days later Rosso received his first payment for the Assumption of the Virgin in the atrium of this church. He was nineteen years old.

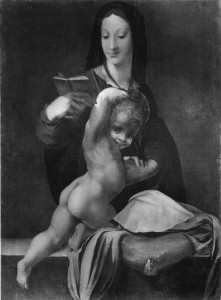

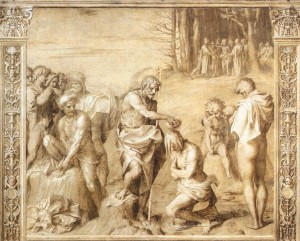

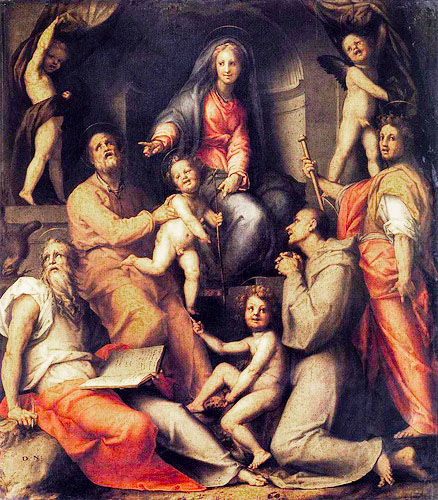

The commission of this fresco followed upon the execution of a small picture for “maestro Giacopo frate de’ Servi,” of “una Nostra Donna con la testa di San Giovanni Evangelista, mezza figura,” mentioned above. Vasari’s description gives a subject that would have been unusual in Florence, and even unique, because of the inclusion of St. John the Evangelist, instead of the Baptist, with the Madonna and Child. Rosso’s lost picture of 1513 seems to be accurately recorded by a copy at Tours (Fig.P.2Aa), and partially by another copy formerly in Milan, with the Evangelist removed, and that seems more affected by the stronger personal style of the copyist (Fig.P.2B). In the middle of the picture, the Child, with his body turned tightly like several of the bathers in the Battle of Cascina, kneels on his right knee into the space of the scene with his buttocks jutting to the left before us. From the very center of the painting, he glances in our direction from under his upraised arm. The half-length St. John, whose mouth is slightly open, turns his eyes upward toward the Child while the Madonna, supporting the Child whose fingers grasp tightly her left hand, reads quietly from a small book that she holds up before her.

Even as a copy, the small picture in Tours is startling, above all else because of the posture of the child and his expression. While the pose of the child appears dependent on Rosso’s personal interpretation of Michelangelo’s nudes in the Cascina cartoon, the emotional temper of this Christ Child seems more related to that of Andrea’s children of around 1512 and 1513, as in his Marriage of St. Catherine in Dresden18 and in his Madonna and Child with the Young St. John the Baptist and Three Angels, known from copies.19 But none of Sarto’s holy children and angels present such a strained posture accompanied by such an emphatic glance at the spectator. The expression of Rosso’s Child brings to mind that of some of the cherubs in his own immediately subsequent Assumption. The Evangelist’s appearance is just as sufficiently out of the ordinary to add further to the eccentricity of the painting. The saint has a slightly wild-eyed look with his open mouth exposing his teeth and suggesting an exceptional emotion, anticipating the figure of St. James in Rosso’s fresco at SS. Annunziata.

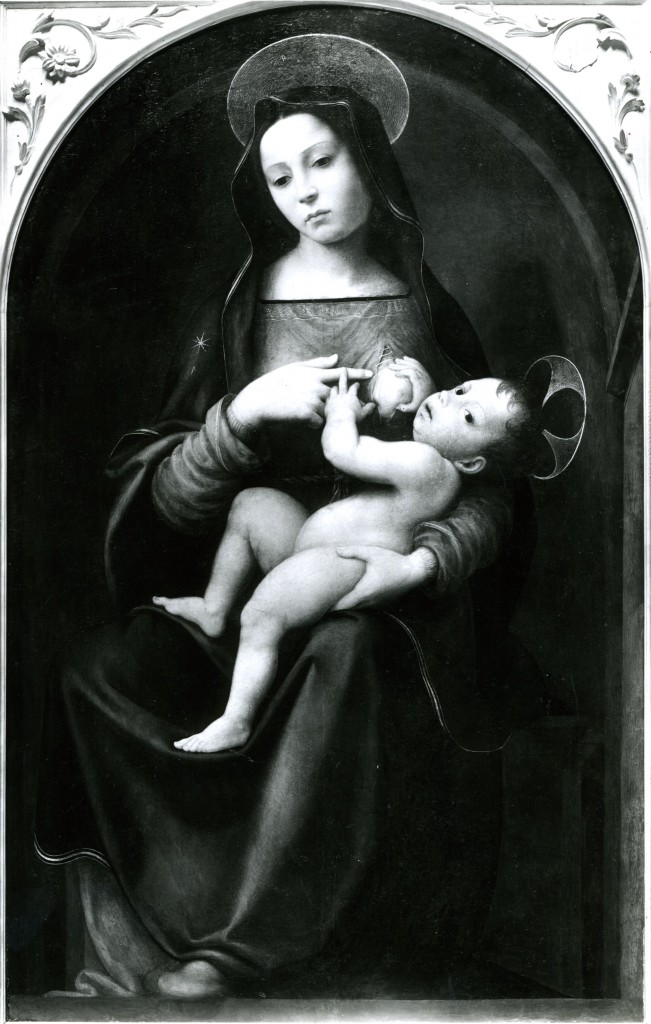

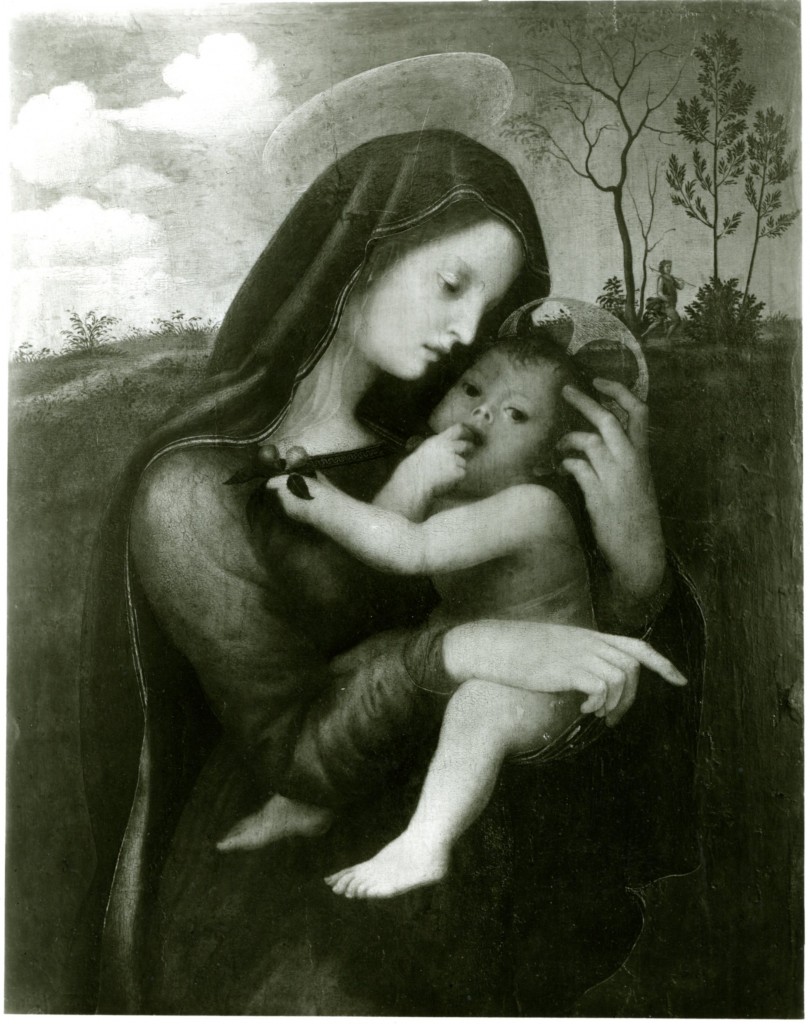

Behind the saint and the Child, the Madonna appears as quite a different kind of figure, neither Michelangelesque nor Sartesque. She brings to mind the women of Fra Bartolommeo and Albertinelli and somewhat more the latter than the former. It may, however, be possible to be even more precise about what Rosso’s Madonna resembles, in spite of the fact that we are dealing with a copy. The shape of the head of the Virgin, the definition of Her features, of Her hand, of the drapery—the folding back of the sleeve at the wrist is a noteworthy detail—are all very similar to stylistic aspects of some of the paintings executed by Giuliano Bugiardini around 1513. Especially close are his Madonna del Latte in the Museo del Cenacolo di San Salvi, Florence,20 and his Madonna and Child in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich.21 The first painting also shows the Madonna, though here full-length, in an arched niche, and a Child who has turned His head to look out at the spectator. Though not in the least Michelangelesque, and hence different from Rosso’s figure, the unusual pose of Bugiardini’s Child and the immediacy of His presence before us are related to Rosso’s figure. But Rosso has chosen to align his Child with the direction of the spectator’s sight, and to use Him in a more unusual and dramatic manner, physically and psychologically, noted by Franklin as related to Leonardo’s novel inventions. What is awkward and touching in Bugiardini’s picture has become a more calculated communication in Rosso’s. Nevertheless the possible stimulus of Bugiardini’s example should not be undervalued. Freedberg has written of the Madonna del Latte that “here the expression has an overtone of intensity that intends to reach us most directly, and the form—as in Albertinelli’s Annunciation of 1510—translates Bartolommeo’s model to the purpose of illusion.”22 The first part of this statement might very well be applied to the picture at Tours—or rather to the more expressively executed, we might suppose, lost original. Freedberg’s second remark introduced us to Rosso’s interest in illusion. This is apparent in the position and foreshortening of the Christ Child in the Tours painting, and in the placement of the saint in the front of the niche. Illusion is also a major factor in Rosso’s Assumption at the Annunziata, which he did immediately after his picture for “maestro Giacopo” and upon his persuasion.

Assuming that the color of the copy at Tours preserves something of the tonality of Rosso’s lost picture, a certain distinctiveness is also recognizable here. The dark green of the Virgin’s head scarf and book and the olive-green of the saint’s garment are seen behind the yellow-orange of the saint’s mantle, a relationship not unlike that of similar colors in the small Uffizi portrait. The effect of the yellow-orange is heightened by the slight abstraction of the saint’s cloak, anticipating the shapes of the drapery in some of Rosso’s later pictures. Could we not then, judging from the Tours picture, introduce Bugiardini as another of the unnamed “pochi maestri” with whom Rosso stayed but a short while? From him, after an initial brief period with Sarto, he was introduced more directly than would have been possible in Andrea’s shop to that of contemporary Florentine art represented by the styles of Fra Bartolommeo and Albertinelli. Early in 1513 Albertinelli retired from painting, breaking up his partnership with the Frate,23 who at that moment, consequently, was probably more in need of a good assistant than a new, young, and contrary student. But it is not at all unlikely, even if the opportunity to study with the Frate presented itself, that Rosso himself would not have wanted to learn from such an authority as, in 1513, Fra Bartolommeo must have appeared to be. Bugiardini, the same age as the Frate, could have served Rosso’s needs very well for instruction in that Bartolommeoesque manner.24

In spite of the possibility of seeing the art of painting in Florence around 1512–1513 as constituting stylistically a cohesive historical moment, from the point of view of a young man entering the profession at this time, the immediate artistic scene may not have looked quite so integrated. The range of contemporary possibilities may have been narrow, but within it certain oppositions were clearly apparent, especially if it was differences that were being sought. Fra Bartolommeo’s tightly conceptualized forms and planar compositions—even when suggesting rotundity—present a dense and stable construction that appears as the aesthetic equivalent of firmly held religious belief.

The implications of this art were in the direction of statements of an absolute order, as it appears in the Frate’s St. Anne Altar and Pitti Pala of 1512. Andrea’s forms are less finite, his compositions more intrinsically spatial, as in his Marriage of St. Catherine in Dresden, and his emotion is more impetuous than Fra Bartolommeo’s. These distinctions need not have been recognized as simply varying degrees of emphasis within otherwise very similar artistic systems, as they can, if it is wished, be seen today. In the early years of the second decade of the sixteenth century, the styles of the Frate and Andrea may have offered very clear alternatives, neither one of which, however, was entirely satisfying to the young Rosso. The picture in Tours may give us an indication of the way in which Rosso, in 1513, faced these styles and used them to serve his own feelings and intuitions, the theological knowledge of the learned Fra Jacopo, who might be seen as his mentor, and just possibly the painter’s clerical brother. The juxtaposed manners of Andrea and the Frate, by way of Bugiardini, and the Michelangelesque elements of the Child, result in an image—incoherent as parts of it may be, and likely more so in the copy at Tours—that is individual and even startling, and not altogether naïve in the bringing together of its sources, the values of which Rosso was also able to appreciate and generally accept. That this picture made for Frate Jacopo has aspects that contribute an artistic innovation “beyond Vasari’s occasional and fairly loose allusions to the maniera moderna,” to quote Franklin,25 is a matter left to a consideration of Rosso’s Assumption of the Virgin at SS. Annunziata, also painted for Fra Jacopo (P.3; Fig.P.3a).

It is unlikely that such a complex picture would have been painted by an artist too attracted by the style of any one master. Its independence from Fra Bartolommeo’s style may have been made possible not only by Rosso’s earlier interest in Sarto’s but also by the example of Bugiardini’s own particular kind of understanding of the Frate’s art and Albertinelli’s. For in addition to any deliberate differences from the Frate’s art, Bugiardini’s indicates as well a certain indifference to and lack of comprehension of the fullest intentions of it. To Rosso the limitations—by comparison with the most accomplished contemporary High Renaissance art in Florence—of Bugiardini’s style may have proved an asset. It may have relieved Rosso of the necessity to take too seriously what to him may have seemed, in Fra Bartolommeo’s style, a too imposing artistic standard. Still Bugiardini’s art would have introduced him to the Frate’s, and at the same time would have indicated to him possibilities for evolving something different from it.

As pointed out earlier, the introduction of the half-length saint is unusual; the appearance of St. John the Evangelist in such a scene may well be unique. His inclusion here with the Madonna and Child presents the three figures who are generally only seen together as a group in pictures of the Crucifixion. In the Tours painting, the Virgin wears a ring on the third finger of her right hand and so can be recognized as the Bride of Christ. Intently she reads from a small book, which she often holds in Florentine pictures, but seldom, if ever, does she give such attention to it. There may be here an allusion to Her at the time of the Annunciation, where, however, she puts it aside to listen to the approaching angel (Fig.Albertinelli, Annunciation and Fig.Sarto, Annunciation). The allusion in this picture painted for Fra Jacopo may also be specifically to the Virgin Annunciate, to whom his church is dedicated. Her foreknowledge of the fate of the impetuous Child may also be suggested by what she reads. John, the apostle “whom Jesus loved” (John 13:23), and to whom Christ gave the care of his mother (John 19:25–27), holds open his book, but glances up from it in the direction of the Child. In the turn of John’s head, the turn of his eyes, and his open mouth, there are signs that he is having a vision, reticent as its expression may be in this early picture by Rosso.26

The larger book that St. John holds could be either his Gospel or the Book of Revelations. But it is only in his Gospel that he has John the Baptist speak of Christ as the bridegroom and mentions the bride (John 3:29: The bride belongs to the bridegroom. The friend who attends the bridegroom waits and listens for him, and is full of joy when he hears the bridegroom’s voice. That joy is mine, and it is now complete). In the Book of Revelations the Bride appears several times, including her appearance as a vision of the new Jerusalem (Revelations 21:2,9–10: And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband… And there came unto me one of the seven angels which had the seven vials full of the seven last plagues, and talked with me, saying, Come hither, I will shew thee the bride, the Lamb’s wife. And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and shewed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God). In his letters to the Corinthians (2 Corinthians 11), the Ephesians (Ephesians 5:22–33), and the Romans (Romans 7), Paul gives the analogy of the Bride to the Church whereby the Virgin becomes the Church that is married to Christ. In Rosso’s high spirited and robust Child the implication may be that of the joyful bridegroom, visually achieved by an infusion of Michelangelo’s energetic nudes into the body of the innocent Child to create the appearance of a mystical rapture.

The details of the subject of the picture and their visionary aspect indicate unusual patronage and an artist who either willingly served it, or desired to invent for it an equally personal form of expression. In this particular case, the patron, mentioned by Vasari, was “maestro Giacopo frate de’ Servi, che attendeva alle poesie” with whom Rosso would have shared his poesia. Immediately thereafter, the friar and theologian obtained for Rosso the commission for the Assumption at the Annunziata and supported him again in 1517 for another fresco. What is known about Fra Jacopo da Firenze indicates a scholar of theology with an interest in poetry, music, and in the decoration of his church, and a person with a degree of local fame.27

Of Rosso’s other early patron, Matteo Bartoli (rather than his son, Piero), some interest in the arts may be indicated for him by the records of his life, but what is certainly known is his family’s wealth.28 The Pucci arms commission (L.8) may have come through Rosso’s connections at the Annunziata rather than through the cardinal’s family. Rosso, of course, knew Sarto and Pontormo, and, we have supposed, Bugiardini as well. As a young man Rosso frequented and seems to have worked in the house of “ser Raffaello di Sandro zoppo, cappellano in San Lorenzo,” in whose rooms at San Lorenzo other artists and musicians, including the young “Messer Antonio da Lucca, musico e sonator di liuto eccellentissimo,” also practiced, whatever precisely these indications mean.29 It can be supposed that his friendship with Raffaello continued until Rosso’s departure for Rome. The cappellano was still alive in 1522–1524 when Perino del Vaga painted a picture for him.30 Probably in 1514, and in the house of “ser Raffaello,” Rosso met Giovanni Antonio Lappoli,31 for whom later, in Arezzo, he designed a Visitation and an Adoration of the Magi.

The degree of conjecture in this account and evaluation of Rosso’s earliest years as an artist is probably no greater than that necessary for the reconstruction of the earliest years of any number of artists’ careers of around this time. However, nothing quite so youthful as his Portrait of a Woman as Mary Magdalen and his Madonna and Child with St. John the Evangelist has generally been accepted for Sarto and Pontormo, although they were also active before their twentieth birthdays. Remembering, especially, the problems of attribution and condition in relating these pictures to Rosso, it would be irrational to insist that what is considered here to have been Rosso’s origins is absolutely correct. Even if eventually considered likely, it could not be completely true. For there must have been very much more that bore upon the initial shaping of Rosso’s mind and sensibility—a few more, perhaps, of those few masters with whom he would not stay for long. However, what is suggested here is reasonable in indicating the beginnings of a career that first presents a surviving documented work from the end of 1513 and the first half of 1514. With this work, the Assumption at SS. Annunziata (Fig.P.3a), Rosso shows himself no longer a juvenile in his profession even though this work did not settle for him what his art would become. Refusing to be anyone’s pupil seems to have deprived Rosso, with his “opinione contraria,” of an experience that might have given him a consolidated artistic position from which to move more directly and easily to a particular manner of his own. His history, however, was not determined this way, and his art, until the end of his career, continues to suggest beginnings that were continuously unsettled. It was probably the strength and independence of Rosso’s interests, and his own wish to exhibit them, that prompted Vasari to characterize Rosso as the young artist with the “opinione contraria” that he gave Vasari to understand.32 It may also have been Vasari’s means sympathetically to suggest Rosso’s artistic origins as he himself spoke of them.33

1 For the major documentation of Rosso’s life and works, including lost works, and for the opinions of other scholars not specifically noted in the text, see the catalogues in Part II of this website. Vasari mentions that Rosso was “di pelo rosso, conforme al nome” (Vasari-Milanesi, V, 1878–1885, 167). While Rosso’s hair is neatly cut (and tonsured?) in the woodcut profile portrait of him in Vasari’s Vite of 1568, his thick beard is kept very long although moderately trimmed. By contrast the frescoed frontal self-portrait in the Royal Elephant in the Gallery of Francis I shows Rosso’s hair longer at the sides and a long shaggy red beard with very long moustaches (Fig.P.22, VI N c and Fig.P.22, VI N d). To set off the color of his hair Rosso shows himself wearing a green garment. Quite unlike Rosso’s is Primaticcio’s appearance with gray or blond hair and a short beard. To Rosso his red hair also carries an effect through its abundance, perhaps going so far as to suggest the power of his own genius even without the appearance of its color. On Vasari’s portraits of Rosso, see P.8 and ns. 3–9. On the woodcut portraits in the Vite of 1568 and the identity of the woodcutter, see also Sharon Gregory, “‘The Outer Man Tends to be a Guide to the Inner’: The Woodcut Portraits in Vasari’s Lives as Parallel Texts,” an unillustrated website version of an essay based upon a chapter in her Ph.D. dissertation, Vasari, Prints and Printmaking, London, Courtauld Institute of Art, 1999.

2 On Rosso’s education, and the opinions on his association with Sarto, see Kusenberg, 1931, 7, and Barocchi, 1950, 17–20, with a review of the earlier literature. Shearman, 1965, I, 23, 166, and 1967, 51, tended to believe that Rosso was Sarto’s pupil although probably not formally apprenticed to him. Hauser, 1965, 178, 190, writes of Rosso as a pupil or follower of Sarto. Freedberg, 1966, col. 582, states that “About 1512 Il Rosso was briefly in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto, probably as an assistant rather than a pupil.” In many respects my remarks in Carroll, 1964 (1976), I, Bk. II, 1–73, are no longer applicable; see instead Carroll, 1987, 14–15. For further opinions on his relation to Sarto, see n. 14.

6 Waldman, 2000, 607, 612, Document 1 (DOC.1a) and Document 3 (DOC.1c), clearly established the identity of Rosso’s father as Jacopo di Guasparre di Giovanni da Civitella and not “maestro Giacopo frate de’ Servi,” as suggested by Berti, 1983, 58.

8 See Shearman, 1965, I, 2, and McKillop, 1974, 9–11. Shearman stated that it is not clear if the artists lived as well as worked at the Sapienza. This group of buildings may have been in the parish of S. Marco (see Shearman, 1965, I, 2, n. 7) in which Rosso lived in 1518 (see document at P.5).

10 On this predella, see Freedberg, 1963, Catalogue Raisonné, 5–6, no. 3, Text and Illustrations, 6–7, Figs. 4–6. The illustrations show the predella without its frame that, in spite of the continuous landscape across the background of all five panels, would have separated the five panels from each other. Like the Borghese predella, the lost predella had the Pietà as its central subject, but its composition showed two angels holding large candles instead of the other figures of the young St. John the Evangelist and Mary Magdalen supporting Christ’s extended body at his head and feet. Sarto’s scene is laid out of doors before rolling hills and mostly young trees before which are also set the four saints. In the lost predella the Pietà is either a night scene or placed inside a dark space that requires light. This Pietà was entirely separated from the prophets at each side.

11 Freedberg, 1963, I, 12, Fig. 23, II, 21–22, as c. 1511; and Shearman, 1965, I, 116–118, Pl. 27a, II, 208–209, as about 1511–512.

12 Freedberg, 1963, I, 12–15, Fig. 24, II, 22–24; and Shearman, 1965, I, 27–28, Pls. 20b–25a, II, 205–207.

13 Freedberg, 1963, I, 15–18, Figs. 32–33, II, 28–32; and Shearman 1965, I, 14–17, Pl. 25b, II, 207.

14 I. Fraenckel, Andrea del Sarto, Strasbourg, 1935, 33, 40, 45, 141, 142, 151, 210, n. 36, 214, 217, thought that Rosso executed the figures in the background of Sarto’s San Gallo Annunciation, the Trinity in his Disputation on the Trinity and the head at the far left in his Scalzo Baptism of the Multitude; these suggestions were justly refuted by Freedberg, 1963, II, 33, 81, and Shearman, 1965, II, 209, 242, 301, although Marcucci, 1955, 250–252, was inclined to see his participation in the Annunciation.

A close connection between Rosso and Sarto was more recently expressed by Berti, 1983, 51, and 1984, 153, who suggested that Rosso was Andrea’s pupil and accompanied him and Pontormo to Rome in 1511. Natali, in Sarto, 1986, 99, 100, with Fig. (Rosso?), and with Cecchi, in Natali and Cecchi, 1989, 6–7, 22, 40, accepted Berti’s hypothesis of an early trip to Rome with Sarto, and recognized Rosso as the author of the heavily draped young man in the immediate left foreground of Sarto’s Procession of the Magi of 1511 at the Annunziata, suggesting also his possible participation in the angels in Sarto’s Birth of the Virgin in the same location. Natali, Paragone, 1989, 27, Fig. 17, again brought up this trip and offered the opinion that Rosso’s figure in the Procession of the Magi is a self-portrait. Ciardi and Mugnaini, 1991, 101, seemed to support Rosso’s authorship of the man in Sarto’s Procession of the Magi. Giorgio Bonsanti, at the Rosso Symposium held at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2 December 1988, identified interventions by Rosso in Sarto’s Holy Family in the Louvre (Inv. 713). On the suggested trip to Rome, see also Franklin, 1994, 56, and Waldman and Franklin, 1999, 109–110, 111, n. 18. See also Costamagna, 1994, 18, 94, n.14, on finding it difficult to envision this early trip to Rome, believing instead that Rosso was tied to the School of San Marco until 1512.

I see no clear evidence in any certain early work by Rosso that he went to Rome prior to his recorded and documented stay of 1524–1527. The search for his hand in Sarto’s works seems to me misguided. In particular, the style of the large foreground figure in Sarto’s Procession is, in its amplitude in space, quite unlike the planar figures in Rosso’s Assumption of 1513–1514. It would also be hard to explain why Sarto would have a seventeen year old assistant paint so important a figure, and a self-portrait at that, in his fresco. Such assistance would imply a relationship between Sarto and Rosso that is not supported by any other evidence. I am inclined to agree with Angiolini, 1986 (1987), 88, that “Il Rosso …non sembra aver conosciuto una fase propriamente sartesca,” or rather exclusively Sartesque for any extended period.

15 See Berti, 1983, 58. The prior’s full name was Jacopo di Battista (see document of 18 April 1517, under P.3). According to Father Eugenio Casalini of SS. Annunziata, as reported by Berti, the prior’s surname seems to have been Rosso or de’Rossi. In 1499 he was in a monastery in Bologna where he probably received his degree in theology, and in 1502 he went to the University of Florence. The following year he was already prior of SS. Annunziata, and still held this position in 1515 and 1516. In 1515 he was elected dean of the Florentine theological faculty. In 1512, the General of the Servites, Fra Aurelio d’Arezzo, sent Fra Jacopo as apostolic visitor to the Provincia dei Servi of Lombardy, with all the powers of the General (see L.7 for the coats-of-arms that Rosso painted for this General in 1513). On 19 October 1528, Fra Jacopo was made part of a commission of four masters of theology to correct and confirm “Statuta nostrae almae Universitatis.” Ciardi and Mugnaini, 1991, 7, recognized him as “il protettore del Rosso.”

16 On this commission of 1517, see under P.3.

18 Freedberg, 1963, I, 19–21, Figs. 38–39, II, 34–35, as 1512–1513; and Shearman, 1965, I, 31–33, 46, Pl. 29, II, 210–211, as about 1512.

19 The Corsini Madonna: Freedberg, 1963, I, 21, Fig. 40, II, 36–38, as c. 1513; and Shearman, 1965, I, 37–40, Pl. 35a (Petworth), II, 217–219, as probably 1513–1514.

20 Dated around 1512–1515 by Freedberg, 1961, I, 208, and 1971, 61, and in the middle of the second decade or c. 1515–1518 by Pagnotta, 1987, 48–49, 204–205, no. 30, Color Pl. II, Fig. 30. If influential on Rosso’s painting for Fra Jacopo, it would have to have been done c. 1512 or 1513, although other pictures by Bugiardini, now lost, could have been seen by him.

21 On the attribution of this picture to Bugiardini, see Federico Zeri, “La riapertura della Alte Pinakothek di Monaco,” Paragone, 95, 1957, 68; Fiorella Sricchia Santoro, “Per il Franciabigio,” Paragone, 163, 1963, 4; and McKillop, 1974, 205. The painting must date from about the same time as Bugiardini’s Madonna del Latte in Florence, as indicated by Pagnotta, 1987, 49–50, 205, no. 31, Fig. 31, as middle of the second decade or c. 1515–1517 (see preceding note).

23 L. Borgo, “Fra Bartolommeo, Albertinelli, and the Pietà for the Certosa of Pavia,” BM, CVIII, 1966, 463; and McKillop, 1974, 23, n. 12.

24 Fischer, 1989, 341, n. 70, was convinced that Rosso was educated in Fra Bartolommeo’s shop prior to 1513 when, according to Fischer, he would have begun to frequent Sarto’s (as elaborated in Fischer’s talk that I did not hear at the Rosso symposium, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2 December 1988). See Béguin, in Empoli e Volterra, 1996 (1994), 92, 97, n. 11). This suggestion was supported by Natali and Cecchi, 1989, 14, and in another context, by Natali, 1991, 146–148, and 1992, 212. The example of the Frate’s art is evident throughout Rosso’s Florentine period, but this was possible without having been in his shop. However, my suggestion of Bugiardini is an alternative to Fischer’s hypothesis, but after an earlier moment with Sarto. It may be of some significance here that Bugiardini was one of the arbiters in a dispute over Rosso’s S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece of 1518 (see under P.5).

26 The placement of the saint is similar to that of St. Zachary, who also holds a book, in Parmigianino’s picture of around 1530, in the Uffizi, which has been considered a Vision of St. Zachary; see Freedberg, 1950, 142, n. 49, 182–184, Fig. 14. The appearance of St. John the Evangelist as a visionary can also be seen in Pontormo’s slightly later Visdomini Altarpiece of 1518.

28 See above, and L.4, n. 1.

30 See Vasari-Milanesi, 1906, VI, 607–608. Vasari (602) says Perino returned to Florence in 1523, but Bernice F. Davidson (Mostra di disegni di Perino del Vaga a la sua cerchia, Florence, 1966, 4, 18) gives 1522. He was again in Rome in 1524 (Freedberg, 1971, 140).

31 Vasari (Vasari-Milanesi, 1906, VI, 6) says Lappoli arrived in Florence just at the time that Pontormo unveiled his frescoes of Faith and Charity at SS. Annunziata, documented November 1513 to June 1514 (Clapp, 1916, 116, 275, Doc. XII). Lappoli seems to have lived in the house of Raffaello from the very beginning of his stay, at which time Rosso appears to have been a visitor there (Vasari-Milanesi, 1906, VI, 7).

32 I was reminded of Vasari’s phrase when reading Gilbert’s (1965, 165) characterization of Machiavelli: “One has sometimes the feeling that whenever Machiavelli read the statement of another writer or heard about a generally accepted view, his first reaction was to discover what would happen if the opposite was maintained.”