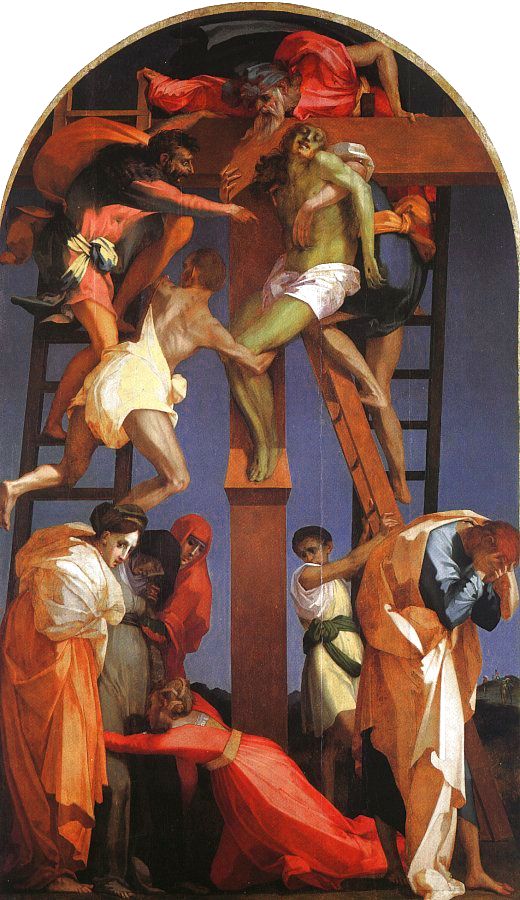

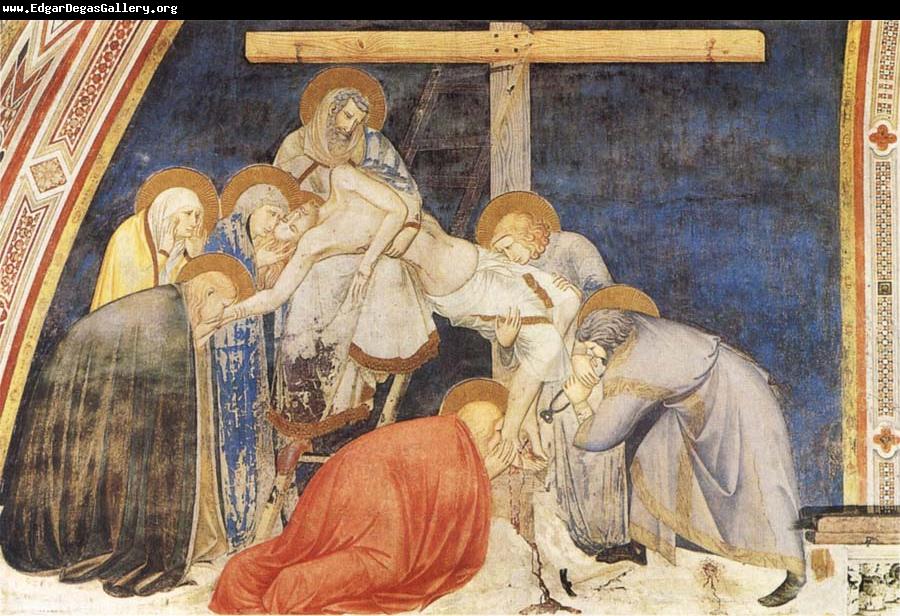

After the document of 3 November 1518 regarding the litigation over the altarpiece intended for the church of Ognissanti there are no records pertaining to Rosso’s artistic activity in Florence until the signature and date on the Dei Altarpiece of 1522 (P.12). On the three years 1519–1521 Vasari wrote but one sentence: “Poi lavorò al signor di Piombino una tavola con Cristo morto bellissimo, e gli fece ancora una cappelluccia: e similmente a Volterra dipinse un bellissimo deposto di Croce.”1 Yet this is the time of his first fully mature accomplishments, the period in which the picture by him recognized since the turn of the twentieth century as his most famous work was executed: the Deposition of 1521 in Volterra (Fig.P.9a). But these are not the years of works that were much known at the time. Of his work in Florence Vasari simply commented in both editions of the Vite: “Et per le case de’cittadini si veggono più quadri, e molti ritratti (L.14A).”

Reviewing in more detail his life and work in Florence may give some idea of why his output was so limited in Florence in these years and what transpired to send Rosso to Piombino and Volterra.

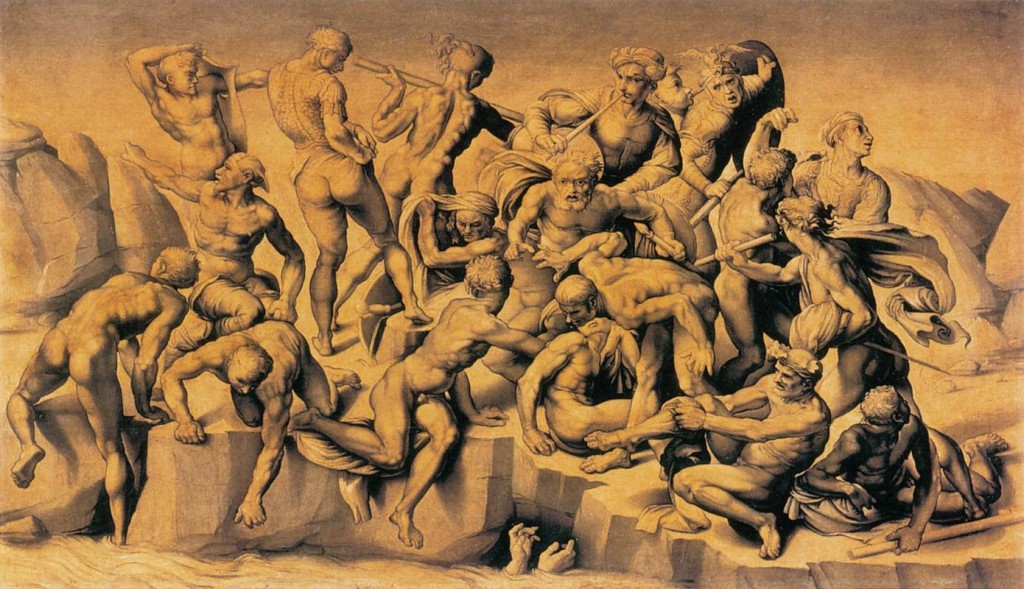

Between the middle of 1515, when Rosso would have heard that his Assumption of the Virgin at the Annunziata was to be destroyed and replaced by Andrea del Sarto, when at the same time he worked on an altarpiece of which the Angel Playing a Lute is a fragment and a large section was reused as the support for the Portrait of a Young Man in Washington, and 30 January 1518 when the contract for the Santa Maria Nuova Altarpiece was made, no major painting is known to have been commissioned from the artist. He was, however, fortunate in the arrival of Agostino Veneziano and in the prints the engraver would make in Florence from works by Sarto and Bandinelli. These circumstances gave Rosso the opportunity to design his Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil in 1517, engraved by Agostino the following year. But its apparent success was not followed by the success of his altarpiece of 1518 for which the artist was not paid the agreed upon price on 6 November. After arbitration was called for by the refusal of the work by the prestigious spedalingo who was shocked by the imagery that Rosso gave him, the artist’s fee was reduced by nine florins of the original twenty-five and Rosso’s painting was removed from sight.

On 18 December 1517, Rosso was brought to the court “nell’arte et università degli Spetiali dell città di Firenze” by one Jacopo di Leonardo da Colle for an indebtedness of eighty-six lire piccioli that the artist had refused to pay, perhaps for pigments he needed for the lost altarpiece of 1514–1515, as suggested earlier. Not having paid this debt again, Jacopo di Leonardo brought the case to the higher Tribunale di Mercanzia on 5 November 1518, where Rosso was ordered to pay his debt, and if he did not he would have to pay a fine of two soldi for each lire owed. On the seventeenth and twenty-fourth of the same month he was called to court again, the fine raised upon each refusal to pay the debt. On 1 December 1518, not only was the fee again raised but it was decreed that the pronouncement of Rosso’s guilt and fines was to be proclaimed loudly throughout Florence.

This history, including financial losses and the shame of public denunciation, presents the collapse of Rosso’s career in Florence. He had now to struggle again toward the recognition of his talents with works of modest size for Florentine houses, as Vasari remarked, and perhaps for small churches and chapels. It would not have been easy for this artist of “una certa opinione contraria alle maniere” of other painters to work his way back to the kind of commissions that had been his with the help of Fra’ Jacopo and perhaps of his clerical brother, Fra’ Filippo, at the Annunziata as well as bear the insult of disregard for his genius and the damage to his pride in his own remarkable individuality. What seems to have happened next is here represented by a number of drawings, a small devotional painting, and two portraits.

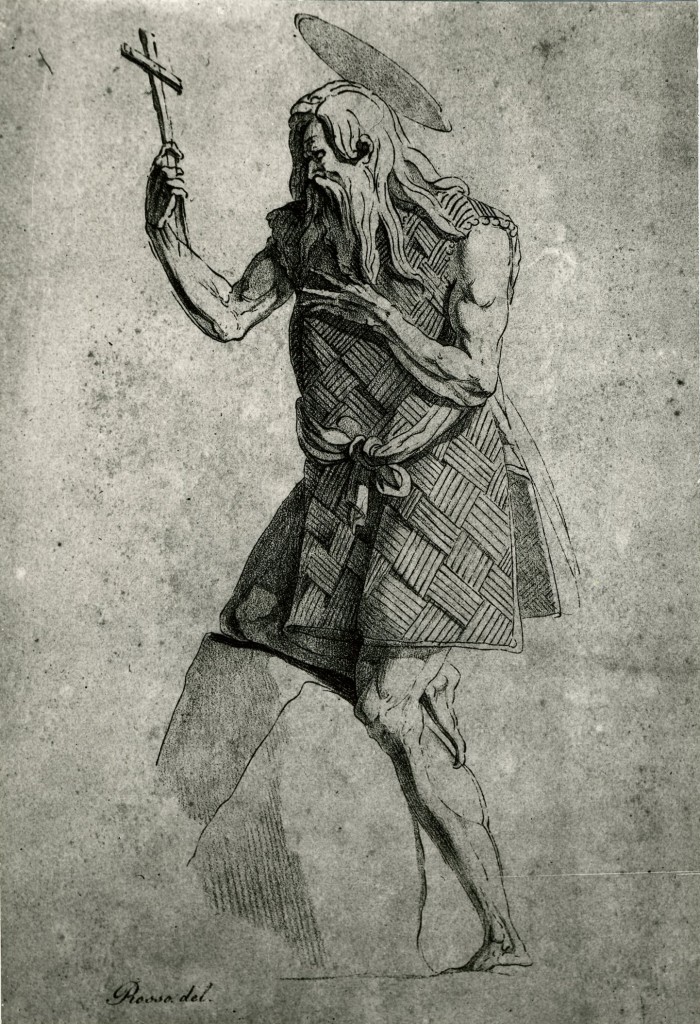

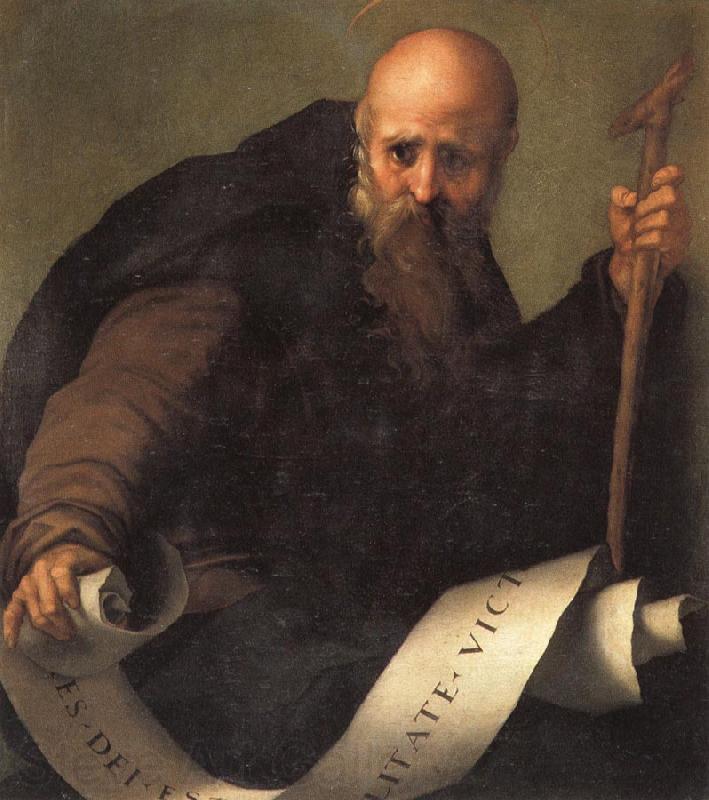

Immediately following the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece are two works, one a drawing representing St. Paul the Hermit in a private collection (Fig.D.3), the other a Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter in the National Gallery in London (P.6). The drawing of the first of the Desert Fathers, whose biography leads those of these anchorite saints written by St. Jerome, may have been done late in 1518 or early in 1519. More likely an original than a fine copy of a lost drawing and otherwise known from a simplified lithographic copy (Fig.D.3 Copy, Lithograph), it is the earliest evidence we have of Rosso’s use of pen and ink and wash. While the appearance of the saint as a thin and bearded old man resembles the figure of St. Jerome in the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece and some of the figures in the Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil of 1517—evident even in such details as the drawing of the knobby muscles and joints—the image of St. Paul is a grander conception. This is visible not only in the greater breadth of his body but also in his pose and gestures that appear more thoughtfully and precisely articulated, and, in their effect, more deeply emotional. It is true that this figure is not grouped with other figures as are the saints in the altarpiece of 1518 and the figures in the drawing made for Agostino Veneziano. Nevertheless, the drama that Paul alone brings forth is less nervous and quick. The expression of feeling throughout the figure is more slowly and carefully paced. The rhythms of the limbs, from the bent right leg to the right arm bent across the body to the raised and bent left arm holding the cross, present a continuity of similar forms and positions that is far more sophisticated than the pose of any figure in an earlier drawing or painting by him. Also, in the flow of the hair and beard and in the tying of the sash around the saint’s waist there is a fullness of forms that is new. Though in most respects the stylistic terms of this image are like those of Rosso’s immediately preceding works there is in this drawing the appearance of an art that is more explicit, more at ease, and yet also more forceful. Here, perhaps, Pontormo’s Visdomini Altarpiece (Fig.Pontormo,Visdomini) set an example for Rosso, or his St. John the Evangelist painted for Pontorme (Fig.Pontormo,Evangelist).2 Perhaps he learned from Michelangelo’s work directly, in particular the St. Matthew (Fig.St.Matthew) with its muscularity and angular shifts of forms, however limited is Rosso’s adaption of them. The light tonality of the St. Paul the Hermit is unlike the darkness and density of the only earlier drawing, the disegno di stampa of 1517. This brightness suggests the coloristic clarity of the figure of St. John the Baptist in the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece, which in turn may have had its effect upon Pontormo.

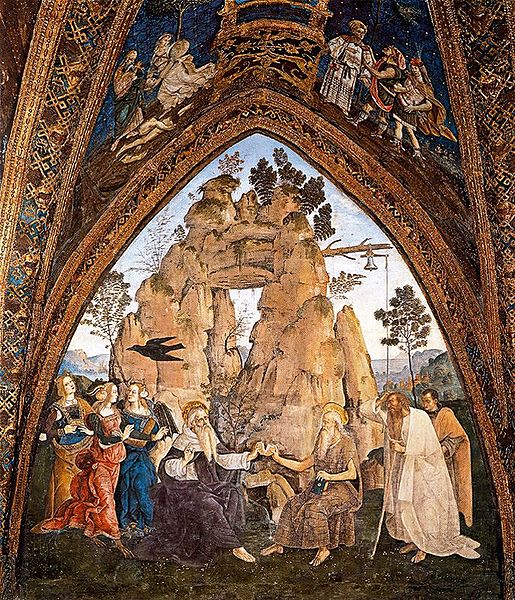

But for the large forms and gestures of Rosso’s anchorite saint he might have been a member of the crowd in the Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil. At the left side of that drawing (Fig.D.1c) the old man doffing his hat wears a garment that shows a large woven pattern at the neck. This pattern covers his entire garment in Agostino Veneziano’s engraving (Fig.E.109a), suggesting that the draughtsman, by this small notation, indicated to the engraver working in Florence to extend it to the whole garment as he did. It is such a dress woven of palm fronds that is the costume of St. Paul the Hermit outside whose rocky abode grew two large date palms that also provided him with nourishment. The rock upon which the saint kneels in Rosso’s drawing is a suggestion of the cave-like abode in which he lived high up and in hiding from imperial persecution. After many years he was discovered by St. Anthony Abbot, as depicted by Pinturrichio around 1492–1494 in the Room of Saints in the Vatican Apartments (Fig.Paul the Hermit). What place this saint might have had in Florence around 1518 or 1519 is still to be discovered. Perhaps the story of St. Paul’s fate and seclusion struck the devout Rosso to identify with this Desert Father following upon the spedalingo‘s condemnation of his altarpiece and the professional persecution it implied

The draftsmanship of St. Paul the Hermit is related to the pen drawing of the Disputation between Two Old Men, but in the St. Paul the Hermit the description of the saint’s special garment with six or seven parallel lines to indicate the fronds, generally shown as Rosso depicts them, prevented the use of the pen for hatching and cross-hatching to create shadows. This can be seen first of all in the small shadows cast by the relief of the individual woven squares. Consequently all the shadows and modeling were done with washes set within contour lines made with the pen. But some details, such as the musculature of the arms, are drawn largely with the brush and various washes. There seems to be no precedent for this precise manner of using pen and ink and wash, but it became, with heightening in white and sometimes done upon tinted paper, one of Rosso’s methods of making highly finished compositional drawings such as the Design for a Chapel of 1528–1529 (Fig.D.37a), and used often in France in drawings for the main frescoes in the Gallery of Francis I at Fontainebleau.

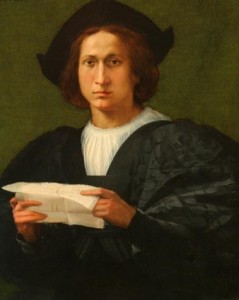

The clarity of presentation in St. Paul the Hermit is also recognizable in Rosso’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter (Fig.P.6a). Dated 22 January 1518 Florentine style on the letter that the figure holds but 1519 by modern reckoning—and assuming that the date records when the picture was made, or begun or finished, and does not commemorate another particular occasion that took place on 22 January—places it immediately after the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The portrait shares with that altarpiece its free execution although not the angular definition of the drapery of the two flanking saints in the Uffizi picture.

The portrait presents a special awareness of the viewer by the sitter looking out at the spectator upon lifting his head from the letter that he has been reading. This action gives to the subject a sense of intelligence that corresponds to what appears to be an aspect of the discourse in the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The body and the head of the figure are held erect and his hands holding the letter are suspended before him. His pose appears sudden and momentary. But the richness of his large costume, the uprightness of his posture, and the directness of his glance give him an authority that indicates his preparedness for any intrusion such as the viewer’s unexpected appearance before him. He seems a gentleman although not a courtier in the terms set down by Baldasarre Castiglione, first published in April of 1528 (when Rosso immediately acquired a copy).

The particular quality of Rosso’s use of a letter in this portrait can be judged by comparison with its role in Franciabigio’s Portrait of a Knight of Rhodes in London (Fig.Franciabigio,London).3 Here the figure is seen somewhat from the side with his head turned in our direction. The full extent of the letter is also visible suggesting that its contents could be available to us, as is not the case in Rosso’s portrait. There is, furthermore, an ease in the relation of Franciabigio’s sitter to the viewer that is quite unlike the stare the viewer faces before Rosso’s young man. He is not separated from us by a parapet or set before a charming landscape, nor is Rosso’s sitter described in such detail as Franciabigio’s.

Like the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece the portrait does not give the impression of having been conceived in terms of drawing. This is particularly evident in the definition of the eyes and of the hands that look painted without the benefit of having learned their anatomy from having studied and drawn them carefully. The hands strike one as inordinately small and stiff against the large forms of the billowing sleeves. The head, therefore, appears quite large, and a sense of spatial tension exists between it and the arms and hands held before his body. No compositional pattern joins them pictorially or brings them together physically. Although somber in tone, the portrait has been provided visual drama, in addition to that given by the slight action of holding up the letter and glancing over it at the viewer, through the juxtaposition of light and dark areas and by the broad spread of the pattern of his steely-gray blue brocade sleeve at the right. Seen against an olive-green background the pink touches of his dark complexion and the slightest indication of pink in the letter’s seal subtly gain in their effect. Though not so finely accomplished a work of art as Sarto’s so-called Portrait of a Sculptor in London (Fig.Sarto,Sculptor), Rosso’s portrait is, at this time in Florence, the finest and most interesting painting of a person and personality other than Andrea’s more impressive and sophisticated portraits.

Both the Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter and the St. Paul the Hermit show the extent of the usage of the terms of Rosso’s early art although neither exhibits the ambitions of the slightly earlier commissioned S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The style of the drawing and the portrait is only slightly enlarged beyond the possibilities suggested by the altarpiece, which itself contains in summation the contents of Rosso’s art of the previous few years.

With hindsight, however, it is apparent that the extraordinary style of the pictures of 1521, the Deposition at Volterra (Fig.P.9a) and the altarpiece from Villamagna (Fig.P.10a), is not merely an extension of what appears in the altarpiece of 1518 that had been rejected. Nevertheless, changes not fully evolved until 1521 are already evident in the St. Paul the Hermit and the approximately contemporary Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter. The largeness of these images is new, especially as it is not merely the result of an abundance of the stuffs that Vasari criticized in the Assumption of 1513–1514. Largeness alone is not so much the issue as is a quality of assurance that comes from the finer use of it. In the drawing that quality of assurance that is visible in the pose of the figure is also in the draftsmanship of it, indicating again that the drawing is autograph. What we see, however, may not be absolutely certain evidence. Still, in the drawing of the hair and of the sash there appears a careful use of line for the creation of shapes and patterns that is found in Rosso’s one earlier surviving drawing, the Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil, that had been made as the model for a print. Looking at the patterns of the saint’s woven garment and those formed by the shapes of the bare white paper and by several values of wash, the aesthetic conception of the St. Paul the Hermit is close to that of the almost monochromatic Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter. The implications of new concerns in these two works are further realized in his slightly later Holy Family with the Young St. John the Baptist in Baltimore (Fig.P.7a) and in his Study for an Altarpiece in the Uffizi (Fig.D.4).

In spite of its small size Rosso’s Holy Family with the Young St. John the Baptist provides good evidence of his personal expression and individual execution around 1519. Perhaps unfinished or only a thinly painted sketch, the Holy Family makes an interesting comparison with Rosso’s altarpiece of 1518. Many of the brushstrokes of the small picture in Baltimore are long and fluid and quite different from the shorter blunt strokes of much of the earlier picture. Furthermore, the contours of the forms are more continuous in the Holy Family. The initial drawing on the panel is visible in many places and is quite unlike the handling of any earlier work. Only the St. Paul the Hermit shows something of the same pliable extended line in Rosso’s painting. This penchant for slender and angular forms and shapes in the altarpiece are not missing from the smaller and slightly later picture, but these are now less rigid and juxtaposed. Instead of the chiseled facets of the drapery of St. John in the altarpiece of 1518 (Fig.P.5d) the straight lines and planes of the Virgin’s drapery in the later picture turn through sharply bent curves. The stiffness of Rosso’s earlier saints has been relaxed and a quality of pliancy has been introduced. Some forms, such as the Virgin’s head and hand, have been elongated and exhibit a new elegance. A coordination of broad planes and long smooth contours, and not the consistent use of chiaroscuro that had been introduced by Leonardo, around 1500, suggest fullness and continuity as seen, for example, in the description of the left leg of the child. Whereas Rosso’s earlier works could fascinate by the diversity and unusualness of their invention, none has that element of poignant grace that is so touching in this small picture and that modulates its strangeness. There is even in this Holy Family a degree of humor, a sign, perhaps, of a humanity that is less anxious than it appears in his earlier works, a humanity that may already be visible in the St. Paul the Hermit. The small painting shows a degree of change that Rosso’s style has undergone since the year before. The modesty of the painting and its unambitious and unfinished character reveal, within the work’s small dimensions, a new but already accomplished draftsmanship and fluid modeling. There is little special interest in color. The monochromatic tonality of the painting is composed of tan-ochre with areas of generally dark green shading. The Holy Family is little more than a sketch but the handling of line and shape and form is deft and secure. So is its use of a somewhat new figural vocabulary.

The little St. John the Baptist is clothed in the simplest brown garment (an animal skin?) without a sleeve that reveals his chubby and muscular arm. He wears a wreath of small grape leaves. These references to Bacchus, current in representations of the saint in other Florentine painting of around the same time, is accompanied by a gesture of prayer toward Christ along with, what seems indicated by his widely open mouth, a loud sound of joy. A cross made of reeds suggests the rustic origins of St. John that is shared with the implications of the grapes leaves related to the rites of ancient Bacchic festivals. A relationship to the pagan past is also an aspect of the humanistic reconciliation of it to the worship of the new Christian God.4 While he stands on a tasseled pillow to indicate his royal status5 he grasps his mother in fear of the implied approach of what lies beyond. Old St. Joseph, with unkempt white hair, moustache, and beard merely watches the reaction of Christ. The Virgin, with an elongated and emphatically upright head, protects her child by her own regal bearing and by her left arm and hand reaching around her son. In the very center of the small painting her left nipple, evident through her garment, indicates the source of nourishment to the infant Christ. Although small and minimally executed Rosso’s Holy Family shows the fullness of the Rosso’s knowledge of what would be sought in a small devotional picture in Florence around 1519 by educated patrons who would have been aware of the special emotional and devotional aspects of this modest painting.6

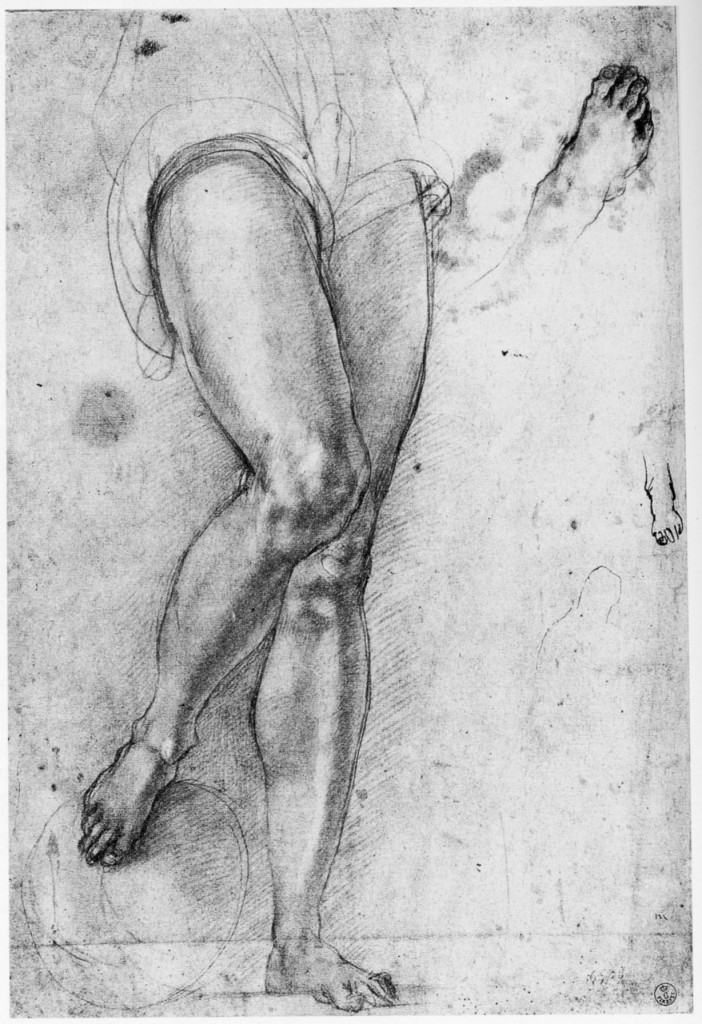

This new vocabulary of fuller, more rounded forms, and of heads with large round eyes is clearly derived from Pontormo. The regular swelling contours of Rosso’s figures, the smooth surfaces of their bodies and the long pointed fingers of the Virgin closely imitate Pontormo’s draftsmanship of around 1519, as in his study for the legs of St. Michael from Pontorme (Fig.Pontormo,Empoli, and Fig.Pontormo,Florence, 6506F) and in the Study for a Pietà, also in the Uffizi (Fig.Pontormo,Florence, 300F recto).7 Although this manner of drawing is already indicated in Pontormo’s slightly earlier painting of Joseph in Egypt (Fig.Pontormo, Joseph in Egypt), for which survives only three rather rough sketches.8 The precise kind of draftsmanship that appears in the immediately subsequent drawings of around 1519 was also new to Pontormo just then, although there are some indications of it in his own earlier drawings. The effect of this draftsmanship is of a supple, subtle and sensuous pliancy that is ultimately derived from Michelangelo. It is neither so fluid nor so emotionally and compositionally forceful in Rosso’s small paintings but, insofar as it has been adopted by him, especially in the Holy Family it has transformed the terms of his rather static and angular style into a much more pliant artistic mode. In retrospect it seems possible to observe that the grandness or largeness of Rosso’s style as seen in his Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter was an end point in the pursuit of the terms of Rosso’s early art. Recognizing the value of certain aspects of Pontormo’s art at this moment and utilizing them sympathetically by putting aside, it would seem, his “opinione contraria” and argumentativeness, Rosso’s art began to achieve, around 1519, its first maturity. If this is too large a conclusion to be drawn from Rosso’s St. Paul the Hermit and from the small picture in Baltimore, it can be further supported by the style of a remarkable contemporary drawing, the Study for an Altarpiece (Fig.D.4).

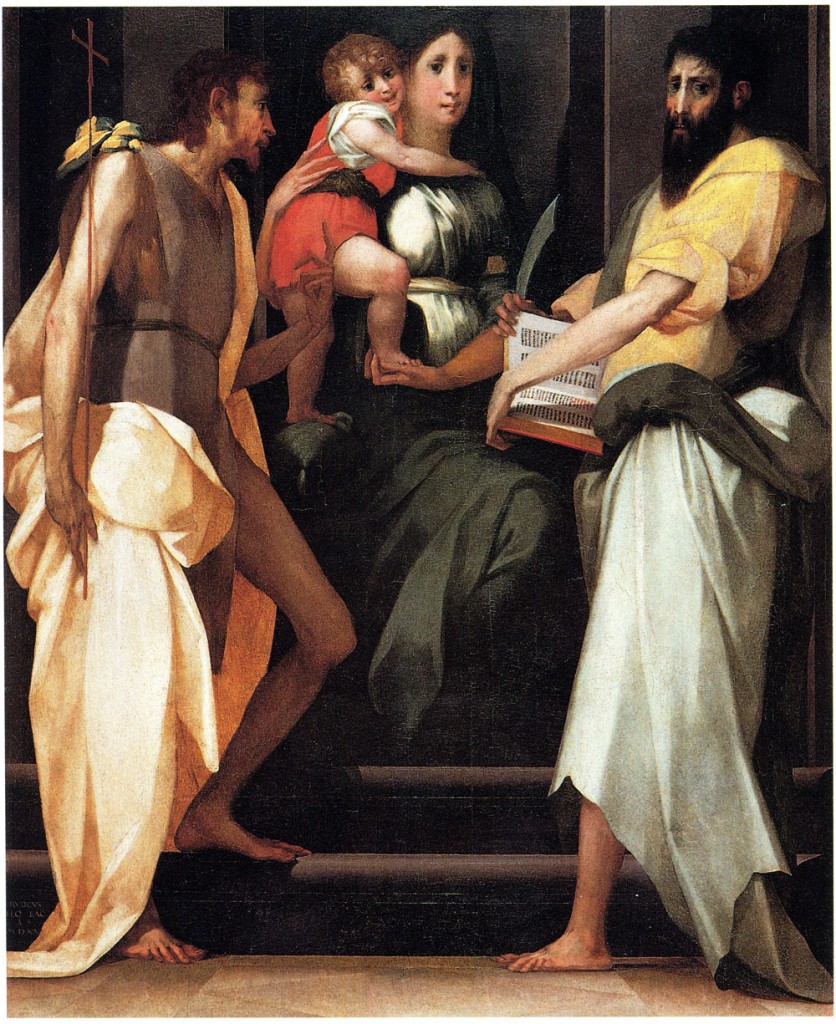

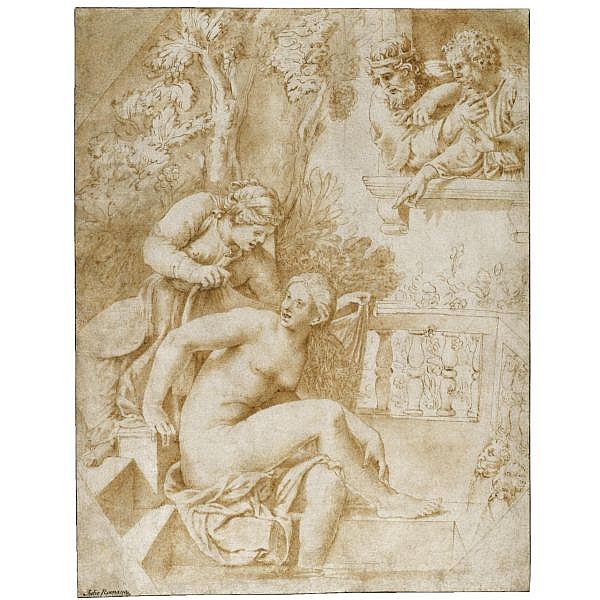

Executed in black chalk, but having the appearance of gray, and on paper with a slight mat texture, the drawing has a degree of finish that is characteristic of almost all of Rosso’s surviving drawings. Compared, however, with the dark Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil (Fig.D.1a), the Study for an Altarpiece appears very light, almost transparent in places. Broad areas of highlight give to the figures a brightness and weightlessness transcending the limits of natural appearance that is generally the descriptive function of light and shade. This kind of tonality is already found in the figure of St. John the Baptist in the altarpiece of 1518 (Fig.P.5d), and in the St. Peter the Hermit (Fig.D.3) of 1518–1519. It becomes even more extraordinary in 1519, resembling Pontormo’s two panels from Pontorme (Fig.Pontormo,Evangelist and Fig.Pontormo,Empoli).9 But it is quite likely that it was Rosso’s art that set the precedent for the submission of chiaroscuro to color and color values, only fully realized by him in the pictures of 1521.

Compared with the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece the slightly later Study for an Altarpiece appears almost like a re-invention of that picture stimulated by an interest in a new set of artistic possibilities. The rigid symmetry of the altarpiece has been subtly broken by the more varied postures of the figures and by the quick shift of physical and psychological expressions across, or rather around, the not very strongly indicated central axis of the composition. St. John the Baptist is seated at the left, the saints at the right are standing. St. John’s almost nude body turns in a manner that complements the posture and movement of St. Sebastian, also almost nude. St. Margaret’s kneeling posture and rich folds of drapery form a counterpoint to the postures and nudity of the two young male saints, and to the broad St. Joseph who is seen standing and largely from the front reading from a book. The postures and gestures of the figures are so interrelated by a tense but pliant grace that one senses here not the argumentative tone of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece but instead a sense of mutual emotion among the saints. Theirs seems not a reaction to the discussion of a point of religious doctrine. Instead the saints seem to be responding to what Joseph is reading from a large book, towards which St. John the Baptist glances and the Virgin, closer to her spouse, seems to look at the text itself within the book. The Christ Child, with one hand touching his mother’s breast, turns his head away and slightly down in the direction of the Baptist’s gesture and of St. Margaret who holds a small book and kneels upon the horned and bat-winged dragon that had swallowed her but from which she escaped though the cross she carried with her that irritated the beast’s stomach. There is an aspect of revelation, suggested by the books, that is further indicated by the bright light that flitters across the figures from the left. These characteristics, as well as details of poses and gestures that give the aspect of a dramatic event, almost certainly indicate that Rosso has been stimulated by Pontormo’s Visdomini altarpiece of 1518 (Fig.Pontormo,Visdomini). But in 1519 Pontomro’s style had also changed from that of his altarpiece, and Rosso was already seeing the Visdomini altarpiece with Pontormo’s more recent art in mind. Pontormo’s St. John the Evangelist and St. Michael are very closely related to Rosso’s figures in the Uffizi drawing that was conceived around the same time.

So thorough does Rosso’s conversion to Pontormo’s style appear to have been at this moment that one might all too easily recognize Rosso’s style in this drawing as merely Pontormesque. In fact, many aspects of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece survive in this drawing: the proportions of the Virgin’s head, the Sartesque flex of a wrist or finger, the interest in emaciated anatomy, the faceted drapery, the arrangement of the figures within a shallow space. Seeing these and other close similarities to his own altarpiece Rosso’s drawing would never actually be mistaken as Pontormo’s. What instead is recognizable, visible also in the Baltimore picture, is the extraordinary maturation of Rosso’s own ability to inflect more precisely the nature of his own sensibility. Given that this sensibility had first been shaped by many of the same sources that lay behind Pontormo’s art it is not altogether surprising that the latter’s art should be so well understood by Rosso. The reverse was also certainly true. What is especially interesting is the use of this understanding beginning possibly at the end of 1518 and fully utilized by Rosso in 1519.

Rosso had known Pontormo at least since around 1512 when, it was reported to Vasari, they worked together on the predella of Sarto’s San Gallo Annunciation. If true, their styles at this very early moment in their careers would probably have been sufficiently similar to Sarto’s style to make it possible for them to work together on this predella. We may know the extent of Rosso’s attachment to Sarto’s art from the style of the Portrait of a Young Woman as Mary Magdalen in the Uffizi (Fig.P.1a). From that time on his and Pontormo’s styles and careers proceeded independently except between 1513 and 1516 when they did adjacent frescoes in the atrium of SS. Annunziata under the patronage of Fra’ Jacopo. By 1518 their styles were quite different as shown by the individual manners of the S. Maria Nuova and Visdomini altarpieces. Still, such differences as there are were derived from very similar sources, a circumstance that all the more points up the extraordinariness of the appearance of these two large but dissimilar works in Florence in the same year. What is also extraordinary is that such different styles in 1518 should have resolved themselves into such similar ones no more than a year later. This may have occurred to some extent because both Rosso and Pontormo recognized the special circumstance of Florentine painting at this moment.

With the death of Fra Bartolommeo in October of 1517 and Sarto’s departure for France in June 1518 Florentine art was without its leading masters.10 It had instead two young but, already at twenty-four, mature rivals for the prestigious position Andrea held. Rather than contending for this position Rosso and Pontormo seem to have supported each other in their individual artistic intentions. Given what Rosso seems to have known of Pontormo’s works of around 1519, such as his drawings and the panels painted for Pontorme, it may be suggested that just at this time Rosso frequented Pontormo’s studio. Knowledge of the publicly exhibited Visdomini altarpiece is not sufficient to explain all the Pontormesque aspects of Rosso’s art around 1519. But why this sudden and exclusive response to Pontormo’s art? It has been suggested that about this time Pontormo made a trip to Rome where he was especially impressed by the Sistine Ceiling.11 No such trip is actually recorded, nor is the evidence for it sufficiently explicit to require this conclusion. It is also possible that Pontormo’s friendship with Michelangelo himself seriously began around 1519 in Florence and that this relationship made possible access to Michelangelo’s drawings. There is no reason to believe they would otherwise have been available to him. In either case it may well have been Pontormo’s direct knowledge of Michelangelo’s Roman works that drew Rosso at this particular moment to Pontormo’s studio. Rosso’s own works do not reveal a close independent study of Michelangelo’s art and one may wonder if his “opinione contraria” may not again have had something to do with his reluctance to gain access to what Pontormo seems to have sought and obtained. For while the suppleness of the bodies in Rosso’s Study for an Altarpiece is Michelangelesque, these bodies are without the physicalness of Michelangelo’s but instead with the appearance of how Pontormo had already subtracted it.

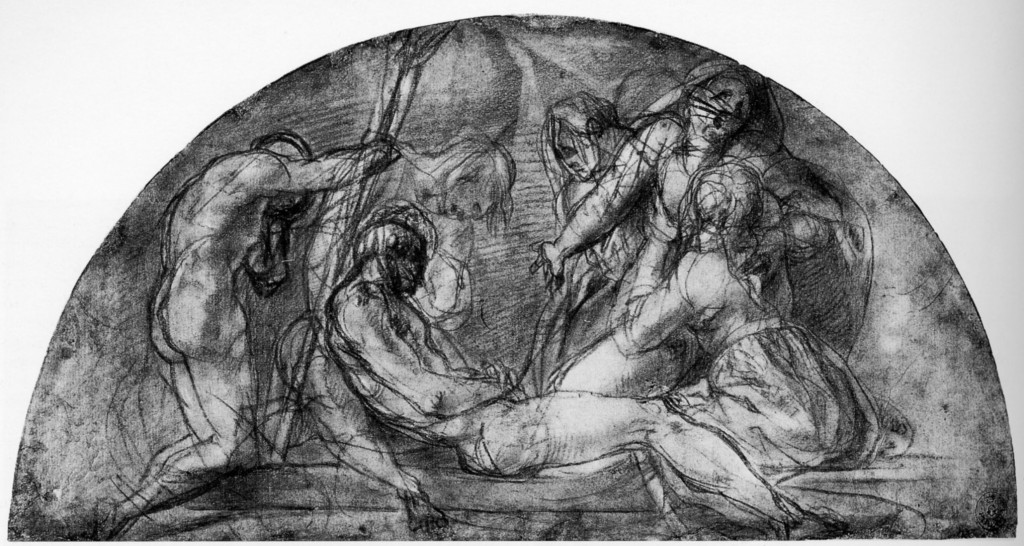

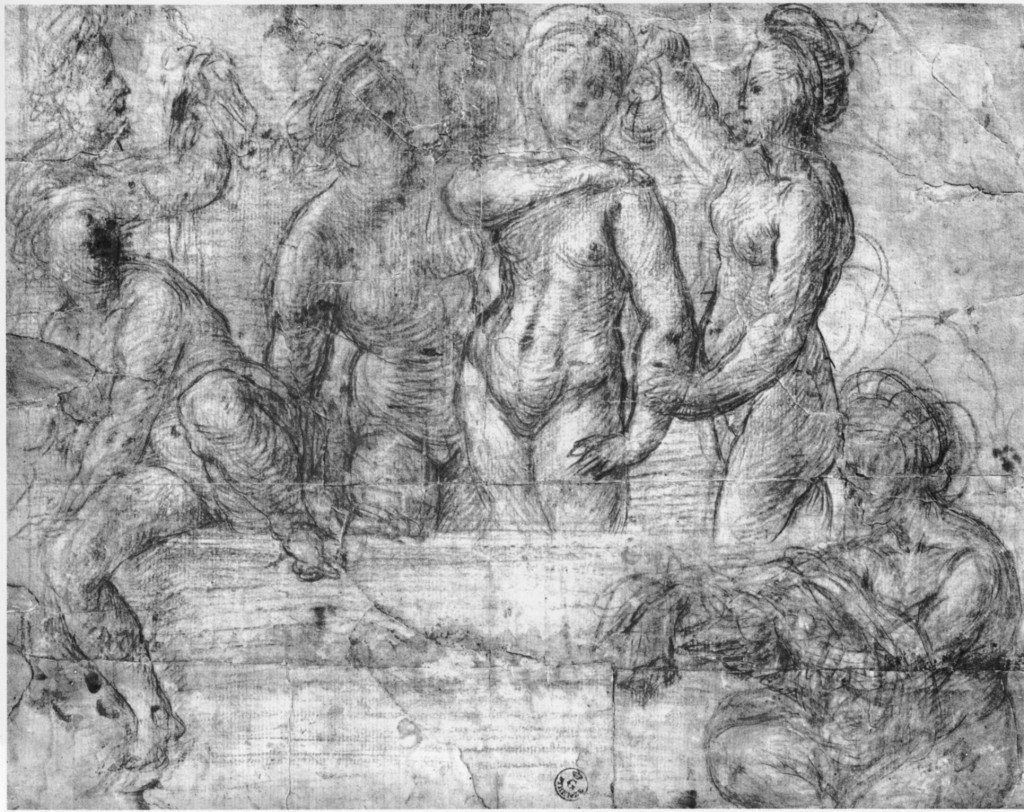

Unlike Pontormo’s Michelangelesque drawings of this moment, such as the Study for St. Michael’s Legs (Fig.Pontormo,Florence, 6506F) and the Study for a Pietà in the Uffizi (Fig.Pontormo,Florence, 300F),12 Rosso’s drawing does not suggest the record of actual observation. The drawing approximates in black chalk the appearance of a finished painting, like Pontormo’s two saints from Pontorme. While individual drawings from models may have been made prior to the execution of this very finished compositional drawing, the drawing itself contains contradictory evidence in regard to the role that such preparatory drawings, if in fact there were any, may have had for Rosso. The figures of St. John and St. Sebastian could first have been studied from life. But the figure of St. Margaret presents another kind of invention. The pose of this woman seen from the back yet turning toward the front is derived, it would seem, from the pose of Michelangelo’s Libyan Sibyl (Fig.Libyan Sibyl). The ornamental character of the drawing, as seen, for example, in the turn of the Virgin’s drapery over her legs, also suggests Michelangelo. Nevertheless, Rosso’s St. Margaret, with its very Bartolommesque head, gives no evidence that Rosso had actually seen Michelangelo’s grand sibyl. Rosso may have had knowledge of it through Pontormo whose Study for a Pietà contains a figure that is dependent on it. Furthemore, the invention of Rosso’s young female saint is very little, if at all, derived from a real understanding of the relation and coordination of the parts of the body in such a kneeling position. The folds of her dress conceal rather than clarify the placement of her limbs. It comes, in fact, as something of a surprise to see her right foot come out from under her skirt. That it has any connection to a leg, knee, and thigh under her garment is little more than a surmise. The same can be said of the turn of her torso that can hardly be perceived at all. The knotting of the large piece of drapery at her back is made more explicit than the turn of the actual substance of her body. Whereas the grace of Michelangelo’s sibyl is an aspect of the density of her body, the grace of Rosso’s saint is little more than the effect made by her lovely garment. At first we hardly notice this, so delighted are we by the dress with its richly faceted folds that are so exquisitely delineated and shaded. The apparent bend of her body seems to give a direction to the planes of her drapery, but in fact once the intricate subtlety of them is appreciated the extent of our interest in the figure is both defined and satisfied. This now seems also to be true to some extent of the other figures, including the two nude youths whose bodies are largely composed of small patterns of discontinuous planes of light and shade bound together by fine and tensely curved contour lines. The head of St. Joseph is composed almost completely of small patches of shadow and large areas of white that make a kind of fixed system out of the vigorous planar draftsmanship of some of Pontormo’s studies for the Visdomini altarpiece.13 But while in that altarpiece and in Pontormo’s drawings for it shadow, and very dark shadow, excavates the forms leaving their most salient features exposed to the light—rather as a figure by Michelangelo is released from a quarried block—in Rosso’s drawing and in Pontormo’s two standing saints from Pontorme light (and color) reduce shadow, making luminous even the darkest areas, and transforms the image from the suggestion of a sudden revelation to the indication of sustained emotion in figures of transcendent form. There is already some aspect of this in the figure of St. John in Rosso’s altarpiece of 1518 and in his Disputation between Two Old Men. The partial suspension of the figures from the facts of corporeal matter leads to a certain attenuation of our belief in them, but what remains of this belief has a special poignancy. On the one hand matter seems to have been surpassed; on the other, however, the success of rendering such beautiful superficiality appears to displace a more profound reality. If it is true that the character of these works by Pontormo and Rosso is to a significant extent dependent on the stimulus of Michelangelo’s art, there was sufficient substance in his figures to support the transformation of it wrought by the two young and admiring compatriots.

So finished a drawing suggests that Rosso had the prospect of an altarpiece in mind. The four figures across the back of the altarpiece compose a Holy Family with an adult St. John the Baptist instead of the infant St. John as in the Baltimore painting. The drama of these figures has become more austere and grander in the implication of impending tragedy, as the Christian worshiper would be prepared to experience. Although, the appearance of these figures might be used in the altarpiece of almost any church or chapel in Florence accompanied by subsidiary saints in the foreground related to the names or the interests of patrons or the site. St. Margaret of Antioch makes a rare showing kneeling atop a dragon that had swallowed her but, by the ill effects of the crucifix she carried, was regurgitated. She is also depicted with a book here, likely the smaller New Testament as distinct from, most likely, the Hebrew bible held by Joseph. (As an afterthought Rosso added the thin lines of a cross across the body of St. John but without any indication of how it is grasped!) St. Margaret appears, again kneeling, in Piero di Cosimo’s altarpiece of the Incarnation, now in the Uffizi (Fig.Incarnation), but painted in 1504 for the Tedaldi Chapel in the church of the Annunziata.14 She is paired with St. Catherine of Alexandria who is a patron of the Dominican Order but also revered by the Servites. More important, however, is St. Sebastian, who is shown, without arrows piercing his flesh, rushing into the scene as though too anxious to join the company of the saintly attendants on the Virgin and Her Child. In this alertness he fulfills his role as one of the saints summoned for protection against the plague, but not necessarily a particular outbreak of it. In Florence the cult of St. Sebastian was significantly established at SS. Annunziata in the Pucci Chapel, the main portal of which was at the right end of the façade, and in the ancient Compagnia di San Sebastiano behind the church, that was reconsecrated in 1516. The Pucci Chapel already had a large altarpiece, Pollaiuolo’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian of 1475, now in the National Gallery in London. The chapel of the Compagnia had, instead of an altarpiece, a reliquary tabernacle preserving a piece of the saint’s head until, in 1529–1530, it commissioned a votive image of the saint from Andrea del Sarto.15 It is possible that Rosso, informed of the reconsecration of the old chapel of the Compagnia di San Sebastiano, possibly by his clerical brother or Fra’ Jacopo, that an altarpiece was being considered for the chapel or imagining the possibility that one would, prepared this Study for an Altarpiece. The subjects of his altarpiece almost certainly indicate a relationship to this particular Compagnia at SS.Annunziata. It was at this church that he had the first commission of his career. So again, here he would start to build his reputation with an altarpiece not of diavoli but also not as a concession to the tastes for the art of Ridolfo Ghirlandaio and the like. The success of this more gracious altarpiece would, he may have hoped, eclipse the failure of his work for the spedalingo of the hospital of S. Maria Nuova.

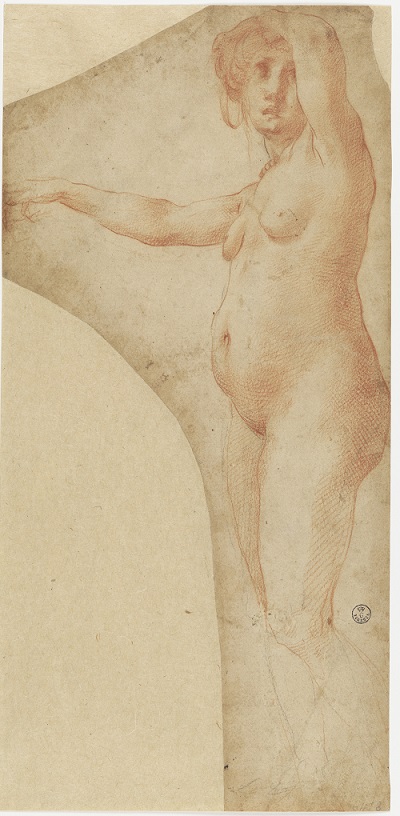

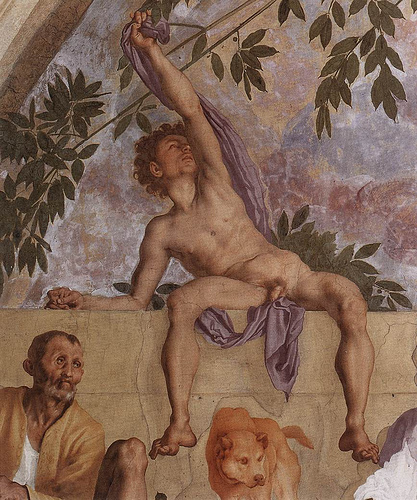

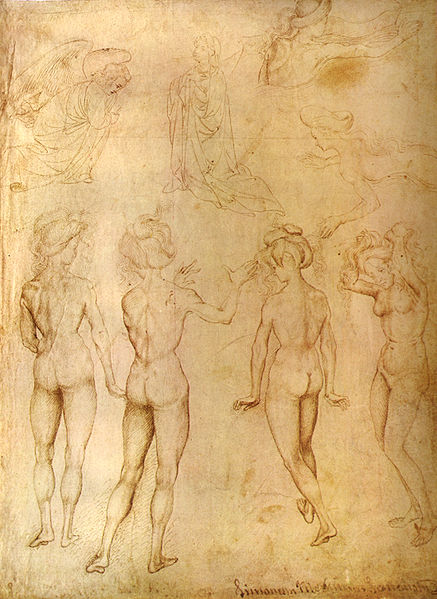

The attraction of Rosso and Pontormo to the art of Michelangelo around 1519 and 152o in Florence constitutes one of the most significant events in the lives of the two young men. The authority of Michelangelo’s art—and possibly the authority of his personality as well—was now for Rosso’s art the inspiration to a grander and graver style. At this moment Michelangelo’s art and person were not yet also the threat that they could later become for Rosso, perhaps because around 1519 its influence came largely through Pontormo. It did not, therefore, stimulate an obvious Michelangelesque manner as it would some years hence in Rome. For at this initial moment of contact Michelangelo’s art suggested an extraordinary variety of possibilities. Only later in the century would there be recognized what might be called a Michelangelesque canon. It is, therefore, very possible to see Pontormo’s St. John the Evangelist as related to Michelangelo’s St. Matthew (Fig.St.Matthew) and the former’s St. Michael as derived in part from Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (Fig.Dying Slave)16 The latter connection is further indicated by Pontormo’s study of the saint’s legs in the Uffizi. Though drawn from life the legs are posed with a recollection of those of Michelangelo’s statue, and are even rendered with a degree of finish that may emulate the surface of Michelangelo’s carved figure. The cherub at St. Michael’s feet brings to mind the concetto of the Slaves with apes similarly placed.17 While the sensuous litheness of the Dying Slave is an aspect of Pontormo’s drawing, in the painting it becomes, through the armor and drapery, a less physical and more buoyant movement that encircles the figure. Probably from the same source, Rosso created around 1520 an even more unusual figure, his Standing Nude Woman in the Uffizi (Fig.D.5). Somewhat later than the Study for an Altarpiece it is even more Pontormesque, especially the nude woman’s face. Its greater naturalism is related to Jacopo’s studies for the lunette at Poggio a Caiano that were done shortly after the saints from Pontorme, but Rosso’s drawing describes another kind of human being than what Pontormo’s drawings seek.18

No earlier work by Rosso quite prepares us for this image of a woman. Her apprehensive upward glance bears a relationship to the Virgin’s expression in the Assumption of the Virgin at SS. Annunziata, and to some extent to St. John’s in the copy at Tours of Rosso’s lost early painting. Except for the bare-breasted hag in the early Disputation drawing of 1517 in the Uffizi, there is no earlier representation of a naked woman in Rosso’s art. Interesting, then, that the Standing Nude Woman should have an expression similar to the Virgin’s in a scene that could be depicted otherwise as an astonishing miraculous event.

The naked woman’s coiffure with its trailing wisps of hair, ribbons, with one having slipped from its place, and a string of beads that falls across her forehead like the few visible beads seen at her neck, suggests a much different context. It is likely that in undressing, or being undressed by a servant, her hair and jewelry were last to be tended to. These last remnants of how she was dressed heighten the sense of her nakedness and of her awareness of the viewer to the right (her left). Her outstretched but slightly limp right arm, as though a garment had just been withdrawn along it, together with her left arm resting on the top of her head in a gesture of fatigue, that has some correspondence to Michelangelo’s Dying Slave. Perhaps hiding her face creates not only a feeling of languor but also of unease. There is here again a suggestion of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave. But there may be more resemblance to the youth who pulls aside his garment and exposes his nakedness, but no unease, in Pontormo’s Vertumnus and Pomona at Poggio a Caiano (Fig.Pontormo,Nude Youth). However, no image of a woman by Pontormo, in a drawing or a painting, and then only much later in his career, appears nude or so cautious as Rosso’s naked lady. Even the studies for the dressed women in Pontormo’s fresco were done from male models.

As a full-length image of a nude woman Rosso’s drawing of around 152o seems to be unique in the history of Italian art up to this time. While it may be presumed to be a study for an undiscovered project, only representations of the story of Bathsheba come to mind, but more because of recollections of how Rembrandt was to characterize Bathsheba (Fig.Rembrandt) than with any suggestions of its rare depiction in early sixteenth century Italy.19 What comes to mind instead is Vasari’s comment that rarely a day passed that he did not draw the nude figure “di natural.” In the inventory of his belongings that he left behind when he fled Arezzo in 1529, twenty-eight sheets of disegni ignudi (L.30) plus one other “ignudo rosso” (L.31) were listed, none of which seem to have survived or been discovered. The young Vasari would have known about these daily nude studies directly from Rosso while he was in Arezzo, the implication being, however, that this habit was not a new one. In his Florentine years he would already have established this discipline and become famous in Rome before he ever arrived there himself because of the drawings that preceded him, i quali erano tenuti meravigliosi, attesto che il Rosso divinissimamente e con gran pulitezza disegnava, as Vasari described them. The Standing Nude Woman is the earliest known drawing to which this appreciation of Rosso’s draftsmanship could be applied.

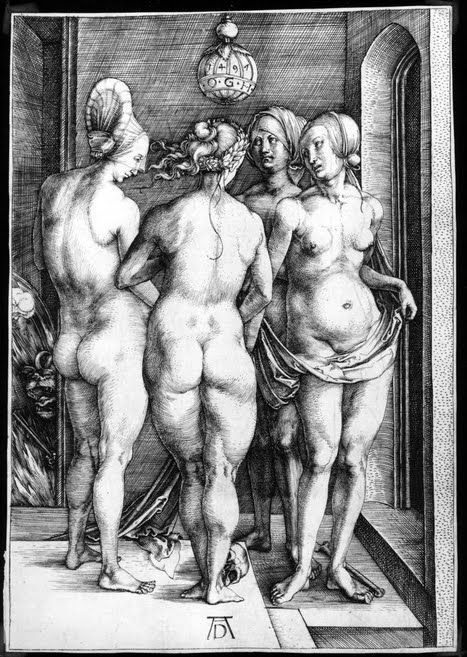

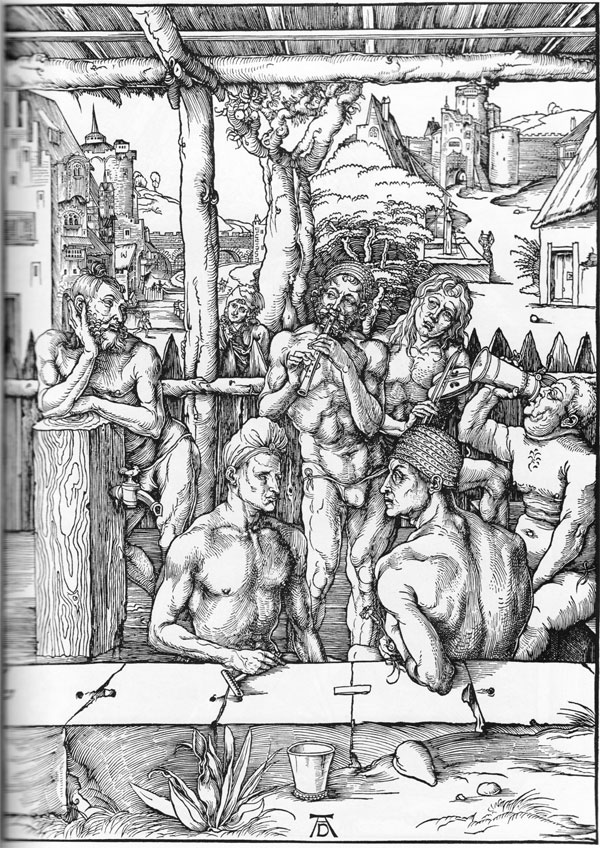

The listing in the Aretine inventory of ignudi need not necessarily refer to drawings of men only, although today’s sympathies and prejudices tend to register this conclusion. On the evidence of the Standing Nude Woman, however, it must be recognized that he also drew from the nude female. Barocchi captioned the illustration of this drawing L’incinta, adding cosidetta in the text. While this is likely not the case, the image of this woman, with her extended abdomen and small sagging breasts, evokes a particular individual and must have been drawn from a nude model that Rosso had before him. The association of a headdress and female nudity, along with the large abdomen of the woman, have their counterparts in some of Dürer’s prints (Fig.Dürer, Naked Women).20 But Dürer’s women are German idealizations that do not show the effects of age that give Rosso’s figure its pathos. This is not to discount or underrate the probable influence of Dürer’s prints. For what is ideal to Dürer was to Rosso an alternative to what was considered the ideal woman in Italian art, such as the Leda in Brussels, attributed to Sarto (Fig.Sarto,Leda)21 that also shows a nude woman with a headdress, as do Leonardo’s earlier representations of the same subject. What Rosso seems to have appreciated in Dürer’s works was their apparent fidelity to nature but not any signs of aging that follow upon the moment of youth’s greatest beauty.

What is so remarkable about the Standing Nude Woman is the absence of any sign of passion or impulsive energy in its draftsmanship that distinguishes it altogether from Pontormo’s drawings. Nor is there any sign in Rosso’s Woman of that quick mode of conceptualization that is characteristic of Sarto’s drawings. Rosso’s drawing appears painstakingly analytical as though feeling, either emotional or tactile, played almost no role in the creation of the image. But the very closeness of the observation of the figure and its graphic analogue in the fine texture of the shading and fine variation of the contours of the drawing indicate a special identification with the subject. This identification, however, seems as guarded as the draftsmanship of the figure is controlled. There is a sense of separation between the observer and what it observed and recorded. The effect of isolation of the figure from the spectator, that comes about through the woman’s pose, has something cruel about it, though this is not to deny the image its human truths regarding beauty, age, sex, and death. Forced to one kind of dramatic conclusion the implications of this drawing will have their ultimate expression in Rosso’s slightly later drawing of Virtù Vanquishing Fortune (Fig.D.6). As Rosso’s attitude of detachment visible in the Standing Nude Woman moves away from immediate experience toward abstraction, these implications will have another kind of ultimate realization, for a moment, in his Moses Killing the Egyptian and Defending the Daughters of Jethro of 1524–1524 (Fig.P.14a).

As the subject of this drawing is not obvious it is difficult to know for what kind of project it might have been done. No surviving painting by Rosso shows a figure that approaches in appearance or feeling the Standing Nude Woman. Nor does she closely resemble any figure in any other early sixteenth-century Italian picture. Most of Rosso’s surviving drawings are not related to paintings by him suggesting that some, perhaps most, of his drawings were never conceived as preparatory to pictures. At the same time this particular drawing is not merely a sketch or a record of a sudden idea. It is a studied invention and yet not altogether a finished work of art or a presentation drawing. There are drawings by Leonardo of this kind that are private in their intentions and for whom no other viewer, or at least no large number of viewers, would have been anticipated. The private concerns that are defined by Rosso’s Standing Nude Woman are of aspects of the human condition that were not part of grand and public art. The transformation of her body from the beauty of its younger form to a still not finally determined older age carries with it the appearance of a similar intermediate psychological state. Not only her upward glance but also her raised arms reveal, as Alberti and Leonardo would have prescribed, the condition of her soul. Realized in this drawing its conception would have been known to few, but one of those might well have been Pontormo. For it is in his Deposition at S. Felicita (Fig.Pontormo,Deposition) and in his Visitation at Carmignano (Fig.Pontormo,Carmignano), more even than in Rosso’s own works, that the implications of this kind of figure were to have their finest fulfillment for public display. Pontormo’s own art, beginning particularly with the panels from Pontorme, anticipated the manner of these later pictures as they also may have anticipated that of Rosso’s own drawing. But around 1520 the responsibility for the invention of this kind of art may have been a shared experience. For a moment, at least, it is just possible that Rosso saw in Pontormo’s art the possibilities of meaning that Pontormo himself then recognized in Rosso’s own works, specifically in such a drawing as this Standing Nude Woman.

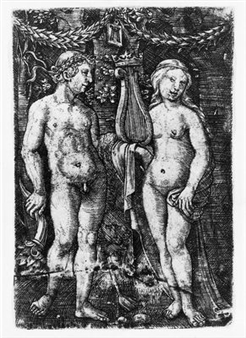

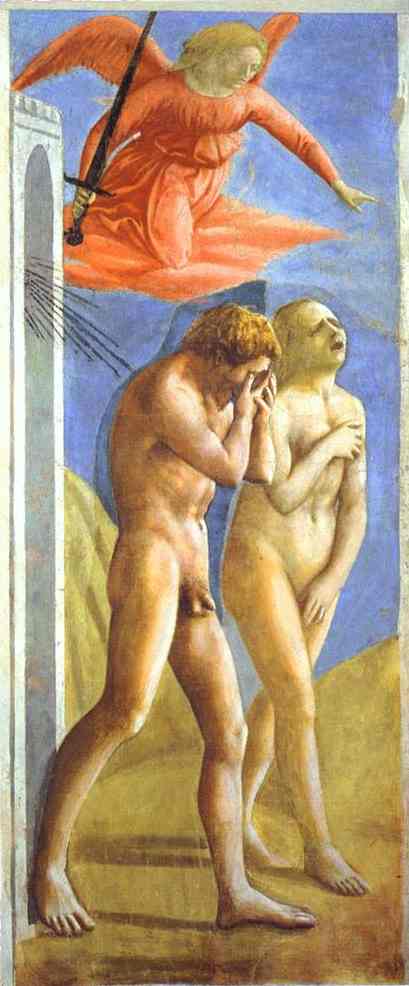

The most important question about this Standing Nude Woman may well be the actual circumstance of the making of this drawing. As it is not clear to what narrative it might be related, the drawing may have also to be considered as one of those studies of nude figures that Rosso did almost every day di naturale, as reported by Vasari. He also relates that Franciabigio in the summer drew daily from male nudes among those that he hired as “uomini salariati.”22 For these studies artists might well have posed their model in anticipation of positions that could be used in their paintings. Rosso seems to have done just this with the cartoon that he made for Domenico Alfani and the composition he composed for Giovanni Antonio Lappoli.23 There are, however, almost no drawings of the female nude by Rosso’s contemporaries in Florence around 1520, or for the next several decades. Few subjects that were painted called for a nude woman: the Creation and Fall of Adam and Eve, David and Bathsheba, and Suzanna and the Elders, for rare examples. The most startling image of female nakedness is Franciabigo’s Story of Bathsheba, dated 1523 (Fig.Franciabigo,Bathsheba), the far left scene of his panel representing the Bath of Bathsheba (Fig.Franciabigio,Bath). None of the other three companion paintings, by Pontormo and Bacchiacca, who did two commissioned for the antechamber of Giovanni Maria Benintendi in Florence, had subjects that required even a single nude women. McKillop found this episode by Franciabigio “difficult to assess, for a nude bathing scene has no precedent, as far as I know, in Florence.”24 She probably meant a female nude bathing scene as Michelangelo’s all male Cascina cartoon of an interrupted bathing scene was well known by then. Francibigio’s major source, McKillop pointed out, was Dürer’s Bath House (Fig.Bath House), known in Florence by 1514, but the great cartoon by Michelangelo must have been recalled by Franciabigio. His female bathing scene in an almost total transsexual version of these sources, small though the painting is. Something similar, as McKillop noted, is the relationship between the “woman seated on the edge of the bath, knee drawn up … to Pontormo’s male studies for the Poggio a Caiano lunette,” a relationship mentioned above.25 It is in Franciabigio’s drawing for his Bath of Bathsheba (Fig.Franciabigio,Florence,14065F) that the model for his sexual translation would likely have first been made, although there might have been individual figure studies drawn beforehand. However, there is nothing in the conception or in the details of these figures that show any individuality. All the women seem to have been invented from the same convention, that Creighton Gilbert, as told to McKillop, related to the figures of Venus and of a Muse in three prints by Albrecht Altdorfer based on Italian sources (Fig.Venus Crouching; Fig.Venus after Bath; Fig.Hercules and Muse).26 That is, Italian prints after Roman sculpture, such as Marcantonio’s Venus at Her Bath (Fig.Marcantonio,Venus), that had brought to Altdorfer the canon of ancient figures. Franciabigio would have known these Italian sources as the model of the female nudes of his Bathsheba and her attendants. Rosso’s Standing Nude Woman does not conform to this antique model. He chose instead to compose his figure from what he observed in the living model that posed for him. Herein lies one of the most important facts about Rosso’s art, one that can be related to Vasari’s comment that Rosso con pochi maestri volle stare all’arte, avendo egli una certa sua opinione contraria alle maniere di quegli. Surely there can again be seen in the Standing Nude Woman what Vasari meant in praising Rosso’s draftsmanship with the comment that he drew divinissimamente e con grand pulitezza.

With so few surviving early drawings it is difficult to know the full evolution of Rosso’s styles of drawing, to determine from his drawings the artists from whom he would have learned the various techniques his few drawings display, and to see how his ways of drawing relate to how he painted. The Standing Nude Woman seems to be Rosso’s earliest drawing that can be related to Vasari’s comments and praise of Rosso’s drawings. There are several reasons why the earliest surviving sheet, the Disputation of 1517, is so dense in its finish. It was made as a disegno di stampa and the first large drawing of this kind that he made. Looked at close-up the contours appears so concise and unbroken and the shading of various values so very tightly hatched and cross-hatched that the draftsmanship carries almost easily visible aesthetic effect of its own. But it does create the darkness of this macabre scene, which, along with the symmetry of the arrangement of the figures, unifies this composition of a large variety of figures. These aspects of the drawing, as well as the numerous details of the figures bring to mind Leonardo’s unfinished Adoration of the Magi (Fig.Leonardo,Magi).

I have not been able to find another early sixteenth-century Florentine drawing of a naked woman that gives evidence of having been done directly from life and meant to record also her particular appearance and her feelings. Pisanello’s drawing of a woman in four poses seen from four sides (Fig.Pisanello) may be closest to Rosso’s figure that I have found.27 In each drawing the woman has abundant hair piled loosely upon her head. One of Pisanello’s women is adjusting the arrangement of her locks. But she is otherwise unlike Rosso’s single Standing Nude Woman. The casualness of Pisanello’s model’s four poses and the sense of her and the viewer’s pleasure that seems to be implied in the showing off of her fine lithe body are details that are not found in Rosso’s full bodied nude with small flat breasts. She looks concerned that someone may be watching her, as though the model was told by the artist to assume the role of Bathsheba anxious over the desires and intentions of King David. Perhaps Rosso thought that he might be selected to do a scene or two for the decoration of the Benintendi antechamber. He had not the opportunity to participate in the earlier decoration of the salotto of Pier Francesco Borgherini. But presenting his drawing of a nude woman as an example of his art would not, perhaps, have won him a place in Borgherini’s artistic ambitions.

There are other important issues related to Rosso’s Standing Nude Woman. Who is this woman and how did it come about that the artist acquired her services as a model? Artists in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries used their assistants to pose for them, clothed and naked, although frequently without clothes even when the final subject was dressed, and represented a man or a woman. Pisanello’s woman might be a foreigner or person used to presenting herself unclothed, as least as the artist has her appear before him. Rosso’s woman is not so comfortable. With beads and ribbons in her hair and also wearing a necklace of beads she looks well off, or at least well kept. He may instead have added these ornaments to her in the drawing, although she could have actually worn these accessories. Does Rosso pay her for modeling when he needs to study the female figure for a picture he is contemplating? As reported above, Vasari noted that for models Franciabigio used “uomini salarati.” Or is modeling just one thing she does to satisfy Rosso who has her as his mistress? Is the emotion she shows wholly related to the subject the artist is going to paint, or is it hers because she had to stand there naked knowing that someone might come in and discover her undressed? Did Rosso direct his female model so that she would show the distress of Bathsheba who was reflecting upon the desires of King David? None of these questions can be answered. But they heighten the suggestion that one of Rosso’s contrary opinions was his study of the human figure based not only on male models but also on real women, and that his close study of both was a way of circumventing antique images of the nude. He saw his models as human beings in their appearance accompanied by emotions that were equally theirs as naturally given or as assigned by the artist. That she may be Bathsheba and yet a Bathsheba unlike the ideal woman that the soon to be widowed wife of Uriah the Hittite always presents, a Bathsheba that carries her history in the appearance of her person, sad, frightened, wary and with small, flat breasts, desirable in King David’s eyes as the artist conceives the story from the model before him.

These preferences would seem to be perfect for painting portraits but only after lengthy practice in seeing what is there and acquiring the techniques to set down on paper what is observed. Rosso’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter of 1519 presents a somewhat awkward attempt to do this. The result resembles a collage of details: his face with eyes that are not well set into the head, his wooden hands without the appearance of mobility, the white pleated shirt that creates its own white shape, and the huge brocade sleeve with its pattern of stylized leaves. The close observation of the sitter was more fully achieved in Rosso’s slightly later Portrait of a Young Man in Washington (Fig.P.8a) and gives to it more of the authority of a specific person than the London portrait. The Washington portrait is more like the Standing Nude Woman in suggesting a particular human and a person with unsettling emotions. The forms of this portrait are larger than in the Portrait of a Young Man with a Letter and its drawing is more controlled and more continuous than in the earlier portrait. The fine hatching of the brushwork of the face, so very unlike the freer and rather haphazard execution of the other portrait, resembles the shading of the Uffizi drawing. Both the largeness of the young man in the Washington portrait and the discipline that has given it its particular shapes of anatomy and costume point again to Rosso’s contact with Pontormo. His approximately contemporary St. Anthony Abbot (Fig.Anthony Abbot),28 rather than his paintings of this very moment, is the closest Florentine parallel to Rosso’s portrait in Washington. The passion of Pontormo’s saint has not, however, been given to Rosso’s young man.

Depicted to below the waist, as are Pontormo’s figures in his recent seated portraits,29 Rosso’s figure appears less close to us than the sitter in his Young Man with a Letter, although no object or activity separates the later figure from us. The strongly foreshortened arm that might lead our attention into the picture, as does the foreshortened arm of Pontormo’s St. Anthony Abbot, instead seems more to project forcefully outward as an almost defiant gesture. As a deterrent to getting too close to the sitter it is comparable to the raised left arm of the Standing Nude Woman, from behind which she glances to the right. In Sarto’s so-called Portrait of a Sculptor (Fig.Sarto,Sculptor) the back, shoulder, and arm of the sitter maintain his distance from us but the bend of his body and the turn of his head as well as the general chiaroscuro of the painting mitigate the severity of his distance. Rosso’s figure stands as straight as his arm juts out. The irregular but clear contours of his shoulders and of his projecting hat seen against the light background subtly alleviate the appearance of rigidity but only as minor variations to the regular large forms and shapes of the portrait. The results are a slightly indeterminate formality of the picture that only partially compensates for its irregularities that include the sitter’s slightly misshapen features. The thrust of his elbow is not matched by a comparably forceful expression on his face. His eyes are slightly veiled, the muscles of his brow are unmoved and his fleshy mouth is not firmly closed resulting in vagueness, even vacuity of expression. His glance indicates his awareness of us but it is not as acute as the raking light that makes him visible to us. The figure verges on appearing haughty but this is not the only effect he makes upon us, as do some later and similar portraits by Bronzino. For the implied authority of his pose and size do not altogether mask the actual flesh and form of his vulnerable individuality. The fresh, though disciplined, execution of the picture still offers the suggestion of sympathies between the sitter and the viewer.

From the limited number of paintings and drawings that have survived, it may be possible to say that Rosso did not have the kind of talent for spontaneous draftsmanship that underlies Sarto’s drawings. Nor that talent for painting, that in Andrea’s hand, is more than the equivalent to what his drawing accomplishes by the addition of a greater range of textures and chiaroscuro and color. Rosso also had not the ambition to make such drawings as Sarto’s magnificent records of what he saw and of what he wanted to get down. The action of drawing was quick and fluid, after intense but possibly quite brief concentration on his subject’s actual form and contours. The spontaneity of Sarto’s draftsmanship is what gives his subjects their life and gives to the human figure and their details, their shining sensuous surfaces. Their actions and gestures are large with comparable indications of emotion and thought, singular rather than complex. His figures are splendid examples of their kind, of beautiful women and handsome men, with fine graceful postures and gestures, dressed in costumes of ample cloth and great folds of rich colors. These compose the aesthetic dramas of his paintings. In the painting of her hair and the colorful shading of her face, Rosso’s Portrait of a Young Woman as Mary Magdalen may reflect the timid intention to imitate Sarto’s sensuous textures. The copies of his lost Madonna and Child with St. John the Evangelist show that Rosso looked elsewhere to the art of Fra Bartolommeo, perhaps to meet what he thought was the mode of a small devotional painting for a cleric, in this instance, Fra’ Jacopo. For his Assumption of 1513–1514, he had the earlier frescoes of Sarto in the atrium of SS. Annunziata to draw upon. He used the stylish young man posing in the left foreground of Sarto’s Procession of the Magi, bundled up in waves of drapery, to serve as the model for the apostles carichi molto di panni, e di troppo dovizia di essi pieni, as Vasari put it.

By the time that he created his Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil, he had learned the tight chiaroscural draftsmanhip that he thought he needed for a disegno di stampa and for the details he wished to describe and the atmosphere he desired for his setting. Again it was the example of Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi that served him here, directly and very probably through Baccio Bandinelli. It was to Rosso that Bandinelli turned to learn how to paint after he failed in his first pursuit to see the techniques and materials of oil painting by witnessing the execution of his own portrait commissioned from Andrea del Sarto sometime between 1515 and 1517. He had first gone to the older and highly successful Sarto because his painting technique was the finest that could be found in Florence. In these years Baccio, born in 1493, had already acquistato nome di grand disegnatore, Vasari tells us. Rosso, a year younger, was approached as a contemporary and, with little experience himself in oil painting, would have had less to teach Baccio. Baccio, however, in exchange, had much to teach Rosso, and the Disputation drawing most likely shows an aspect of what Rosso learned from the “great draftsman.”30

In the Disputation between Two Old Men another aspect of Bandnelli’s drawings was taken as its graphic mode, a quick and clear penmanship of sharply defined contours, of the men’s faces, with large planes of parallel hatching, of varied closeness, and cross-hatching for the darkest shadows. Hands are as sharply drawn as the gestures they described. Bandinelli, himself, never used pen and ink so masterfully nor conceived of figures so driven in their emotions. The quickly made parallel strokes to create shading in Rosso’s drawing appear as parallel strokes of his brush in the description of the angular folds of the drapery of Saints John the Baptist (Fig.P.5d) and Jerome (Fig.P.5g) in the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece of 1519. They also heighten the effect of the dialectic of the figures.

Rosso would not have learned from Bandinelli the use of wash to accompany pen and ink that appears in his St. Paul the Hermit, known from what seemed a copy but that is so surely done to appear at times autograph. Its penmanship describes the contours of the muscles and of the bones of his fingers, wrists and knees of the saint. The shading of the figure, however, is produced by washes, not by parallel pen and ink hatching and cross hatching as in Rosso’s Disputation between Two Old Men, as learned from Bandinelli. Shading was rarely used in figure drawing of the early sixteenth century although it can already be found in the previous century, and even earlier.31 Beginning in the late 1520s, it was used by Rosso in very finished large drawings, also heightened in white, and in France for the drawings made for the frescoed scenes in Gallery of Francis I. What caused Rosso to use it in the St. Paul the Hermit may well be the saint’s garment, by which he is identified, made of woven palm fronds that are always carefully depicted. Rosso gave great attention to the description of this garment as a series of squares, each with six or eight parallel lines to suggest each frond of a palm leaf, set opposite to each other to indicate the weave of the whole garment. He could not or wished not, then, to shade this garment with other parallel lines of hatching or cross-hatching. Instead he chose to use a wash, not only for the shading under each frond but also for the shading throughout the drawing, including the shadow on the rock. It is possible that this use of pen and ink and wash is newly invented here and in other lost drawings of around this time and may have some bearing on how he painted his Deposition of 1521.

The execution of the Study for an Altarpiece of around 1519 has much in common with the execution of the St. Paul the Hermit in spite of the differences of media. The musculature of the old anchorite is much like the anatomy of St. John’s arms in that altarpiece drawing and the smoothness of the shading in black chalk of the latter has much the same texture as the washes in the earlier drawing. The fine lines of the altarpiece drawing are just as thin as the pen lines that outline St. Paul the Hermit’s arms and legs. There is also the same flattening of the figures parallel to the front plane of the drawing that finds its way further explored in the Volterra Deposition. There the garments of the figures show the same lightness and transparency of the cloth that sweeps across, and knots and folds upon the Virgin and St. Margaret in the black chalk drawing. Like the special light that gives its unusual effect to the lowering of Christ’s body and to the grief of his beloved ones, so, too, an unusual light in the altarpiece drawing creates a scene of transcendence. Rosso’s Standing Nude Woman has already the form and physiognomy of the holy women in the Deposition of 1521, and emotion derived from observed and felt experience.

Vasari wrote that Rosso made for the “Signor di Piombino”, Jacopo V Appiano: “una tavola con un Cristo morto bellissimo” (L.15) and “una cappelluccia” (L.16). These two works are mentioned just before the Volterra Deposition of 1521 and immediately after the arch designed by Rosso and erected for the entry of Leo X into Florence in 1515 (L.12). Vasari was mistaken in placing the arch and, at the Annunziata, the arms of Leo X after the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece of 1518. Documents now make clear that Rosso’s “Cristo morto” and the “cappellucia” were made in 1520—begun, that is, after 22 February 1519, the date, in modern style, on the letter of the male portrait in London—and perhaps not finished until January of 1521, and that both were done in Piombino (DOC.6b; DOC. 7; DOC. 7a).

Although Vasari names Jacopo V Appiani, the Lord of Piombino, as Rosso’s patron, one of the two works and possibly both were made for the confraternity of the Corpus Christi. Its altar was located in the principal church of Piombino, the pieve of Santi Lorenzo e Antimo (much destroyed under Napoleonic rule), whose “‘juspatronatas’ was officially assigned to Jacopo V Appiani in 1517 by Pope Leo X.”32 The “Cristo morto bellissimo was noted by Vasari as a “tavola,” a panel painting. It has been suggested that its subject would have been “one of the Passion mysteries after he Crucifixion.”33 However, Vasari’s usage of the title “Cristo morto” generally refers to a picture like Rosso’s painting in Boston (Fig.P.18a).

It has been suggested that Vasari’s reference to a “cappelluccia” indicates the decoration, “probably in fresco”, although Vasari later comments that Rosso “fu sempre nemico del lavorare in fresco”, of a small chapel, perhaps in Sant’Agostino. The decoration of a chapel probably cannot be dismissed as a possibility, nor excluded even if another project with equal likelihood of being true may also be suggested, that is, a small architectural work. Such a “cappellucia” would lend some support, along with the arch of 1515, to Vasari’s remark early in his “Life” of Rosso that “Nell’architettura fu eccellentissino e straordinario”34 The panel painting of the Dead Christ could then have been the exquisite small altarpiece of this fine small chapel.35

Just as Vasari mentioned only Rosso’s employment by the Lord of Piombino so is it likely that the ambitious artist also had seen the prestige of this commission as an important reason for accepting it. In Florence he had lost his chances for success due to the lack of satisfaction that he and his work gave to those who ventured to hire him. But his talent, even genius, may still have found respect, which led the confraternity of the Corpus Christi and the Lord of Piombino to find him in their search for a fine Florentine artist who would leave Florence to work in Piombino. Contact could have been made through Fra’ Jacopo or Rosso’s brother at SS. Annunziata with the clerics at the pieve di Santi Lorenzo e Antimo in Piombino. Rosso was greatly in need of commissions and, if possible, important patronage, the confraternity in Piombino needed an artist for the works of art that a recent gift may have made possible, and Jacopo V Appiani could have recognized the value of fine works of art for the state of which he had just received confirmation and investiture from Charles V. Rosso, like St. Paul the Hermit, needed his own seclusion from those in Florence who would be aware of his professional misfortunes.

Rosso’s work at Piombino must have been sufficiently successful to warrant another commission from another religious body in Volterra, 50 or 60 kilometers northeast of Piombino and on one route that the artist could have chosen to return home. He was first recorded in Volterra on 8 April 1521, (DOC.7) just three months since he was last recorded in Piombino. He was back in Florence by 9 September (DOC.7a).

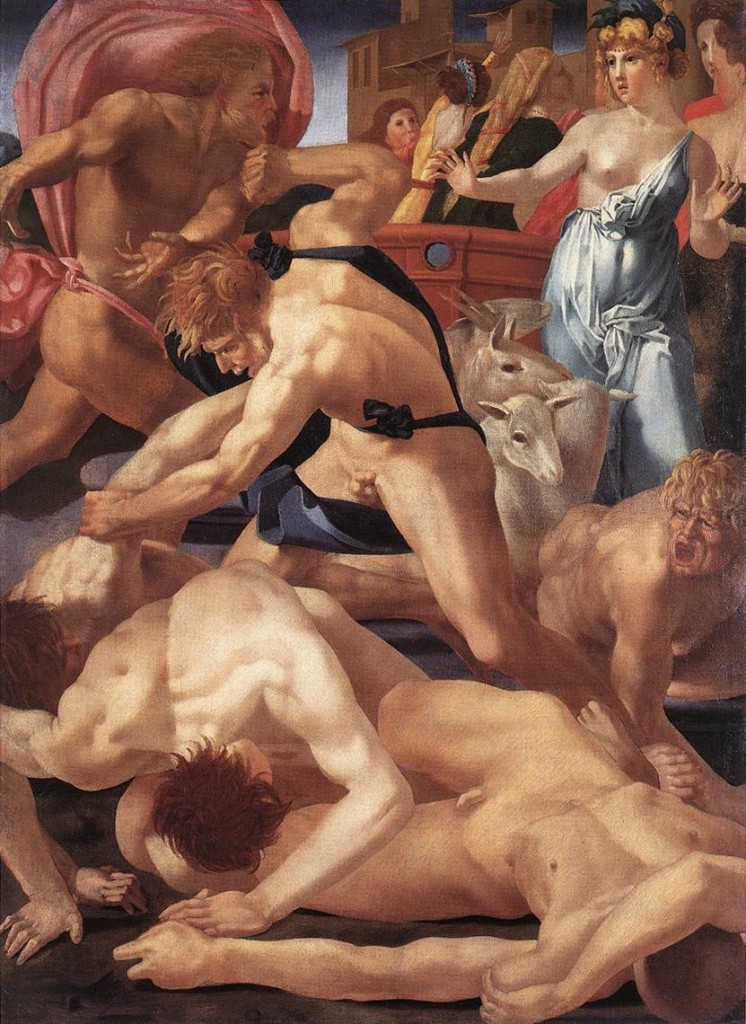

It was in the drawings and small paintings of 1519 and 1520, including the lost works that he did in Piombino, that Rosso was prepared for his largest and most expressive work to date, the Deposition of 1521 now in the Pinacoteca in Volterra (Fig.P.9). Nevertheless, it would be misleading to ignore his earlier works as also anticipating, in many ways, what we see in that extraordinary altarpiece. There is not a single preceding work that does not contain some aspect of style or feeling that appears in this Deposition. Nothing should be more likely. But it is also possible to see the Deposition as so different from most of his earlier works as to misrepresent, to some extent, the nature of its novelty. For so transformed is its appearance from that of the Assumption of 1513–1514 that it would be very hard, without other evidence, to recognize them as by the same artist. This might also be said of Pontormo’s Visitation of 1514–1516 at SS. Annunziata (Fig.Pontromo,Visitation) and his altarpiece of around 1528 of the same subject at Carmignano (Fig.Pontormo,Carmignano), though more years separate these two works. The dissimilarity of these pairs of pictures clearly indicates the changes that took place between early and only slightly later sixteenth-century Florentine art, changes that have long been recognized since the turn of the twentieth century. So much so that their stylistic similarities can now be easily overlooked. In spite of its diversity Rosso’s art can be shown to have recurrent, if not consistently recurrent, forms and expressions that are fundamental to the character of his Volterra Deposition.

It is not necessary to compare the Deposition with all of Rosso’s earlier works, but it must be looked at in relation to the only other earlier painting of comparable size, the Annunziata Assumption. The nature of the commissions of these two paintings was probably not significantly different. Both were made for established religious organizations, and both were made for public exhibition, though the later one was painted for the chapel of a confraternity attached to a large church in a small town. This isolation may have been fortunate for Rosso in 1521. In 1513–1514 quite the reverse would have been true: working in a public place in Florence should have had its advantages for the very young artist. But since the refusal of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece Rosso’s situation in Florence had changed. Speaking in the broadest terms, neither picture is thematically unusual and no especially unusual circumstances need lay behind the conception of either, though at least one particular condition can be related to an aspect of the Deposition. Both pictures meet the terms of grand invention and expression that had been determined for Florentine painting by the middle of the second decade of the sixteenth century. Although the subjects of Rosso’s pictures are different they are both subjects that contain an upper and lower event, and in both paintings this factor controls their conception in a special way. The figures below are separated from those above, physically and psychologically, and this separateness becomes an issue of meaning for Rosso. There is only a minimum of response of the apostles to the Virgin rising above them; not one of the lower figures in the Deposition gives his attention to Christ’s body that is seen still high up against the cross. The isolation of the upper event, and especially the isolation of the major figure of that event from those below who might give their full attention to it, leaves the spectator partly alone to contemplate what the picture’s meaning might be. We are not altogether witnesses either to the Virgin’s elevation to heaven or to the aftermath of Christ’s death from the same point of view as those below in these pictures who are part of the context of these scenes. In fact, our attention to and our sympathies with their reactions do not lead us to the fullest possible understanding of what is happening above their heads. But the independence of our position is not complete because of the extraordinary closeness of these figures to us. In both pictures they are so near the picture plane, marked by architectural moldings in the Assumption and by the front of a ledge in the Deposition, that details actually appear to extend in front of it. The resulting dualism of our situation is a fundamental aspect of the invention of these pictures, and one that determines and constitutes the deepest level of their meaning. As these two pictures share this dualism, so they share the meaning it creates. Where they differ stylistically they give, of course, evidence of the history of Rosso’s maturation that leads from the Assumption of 1513–1514 to the Deposition of 1521. The thin old man, here Joseph of Arimathea, that appears above the ladder in the Deposition had already become established as a type in Rosso’s art by 1518, in the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The angular poses and gestures in the Deposition are also already found in the altarpiece of 1518 and create a comparable appearance of urgent purpose and meaning in the men that lower Christ’s body and in the figure of the Magdalen. However, the precise nature of the energetic thrust of their gestures and attention is more like that in Rosso’s Disputation between Two Old Men of 1518–1519. Here the angularity of the drapery and the faceted planes of light and shade resemble, too, the drapery in the picture in Volterra. Insofar as it is possible to speak of angularity as becoming cursive it had already become so under the influence of Pontormo’s art and with a tense resiliency in the Study for a Altarpiece of around 1519 (D.4). Consequently Rosso’s forms have in turn become more connected and more corresponding, even as some are placed in opposition to one another. No earlier work by Rosso reveals its intentions so precisely. And yet, looking now at the Deposition of 1521 it is evident that the accomplishment of the earlier drawing led to an even more precise formulation of its style. The ambiguities of St. Margaret and vague conception and description of St. Joseph are nowhere to be found in the later painting. These two saints are, it is true, not part of a very dramatic situation, but even as meditative figures their appearance is still somewhat without that sense of purpose that seems to control the more active attitudes of the other figures in the drawing. The counterbalancing of outward activity and inwardly directed stillness in the Deposition achieves a sharper and more poignant effect. And where it is quiet, as in the woman at the far left and in the young man holding the ladder, the picture implies a search for understanding, as does the Standing Nude Woman, rather than a declaration of it. In a more hesitant and less stringent manner Rosso’s Assumption of eight years before also posed a comparable quest for meaning.

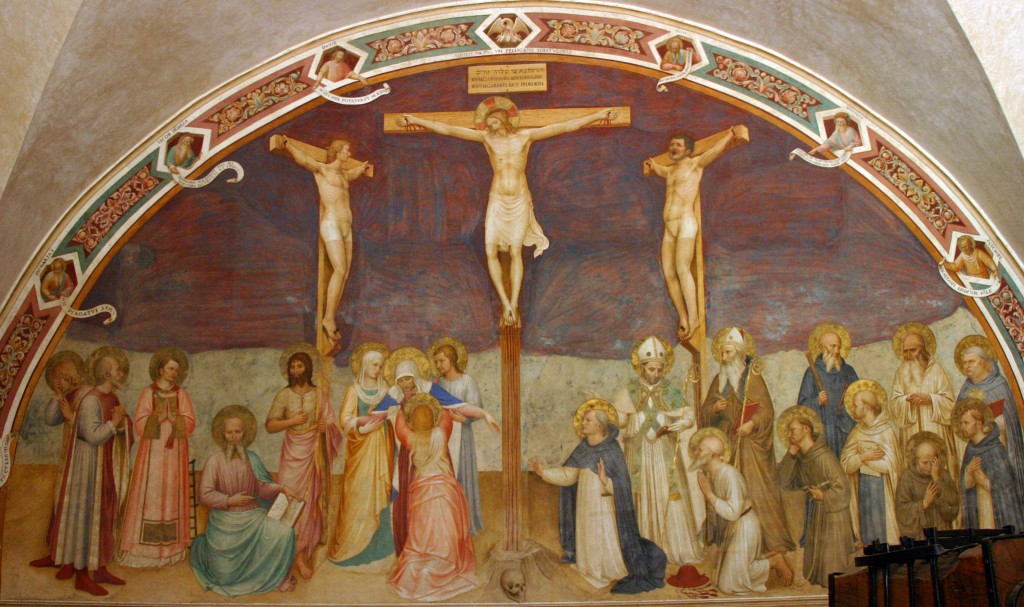

It has generally been recognized that the scene of Rosso’s painting is dependent upon the very large Deposition commissioned from Filippino Lippi in 1503 and given to Perugino to complete late in 1505 (Fig.Lippi-Perugino).36 Details of these two pictures are sufficiently similar to guarantee this relation, and the original location of the earlier painting on the high altar of SS. Annunziata provides almost certain proof that Rosso knew it. The use of ladders propped up against the cross-arms of the cross, the pose of one man on a ladder seen from the back, the old Joseph of Arimathea with a long beard high up in the picture, the energetic activity of the lowering of Christ’s body, the low horizon, the grouping of the women at the left, the relatively isolated male figure at the right, and the standing young figure at the right of the cross are all elements of the Annunziata Deposition that have some degree of correspondence in Rosso’s altarpiece. The theme of the Deposition was not so frequent to have provided Rosso with many precedents. No known Deposition other than Filippino and Perugino’s appears to be so closely related to Rosso’s own version. Upon its creation it became the most authoritative depiction of this theme. One other lost Deposition may have influenced Rosso, that by Sarto and Franciabigio on a curtain for the high altar of SS. Annunziata, but that, too, according to Vasari, was similar to the Filippino and Perugino altarpiece.37