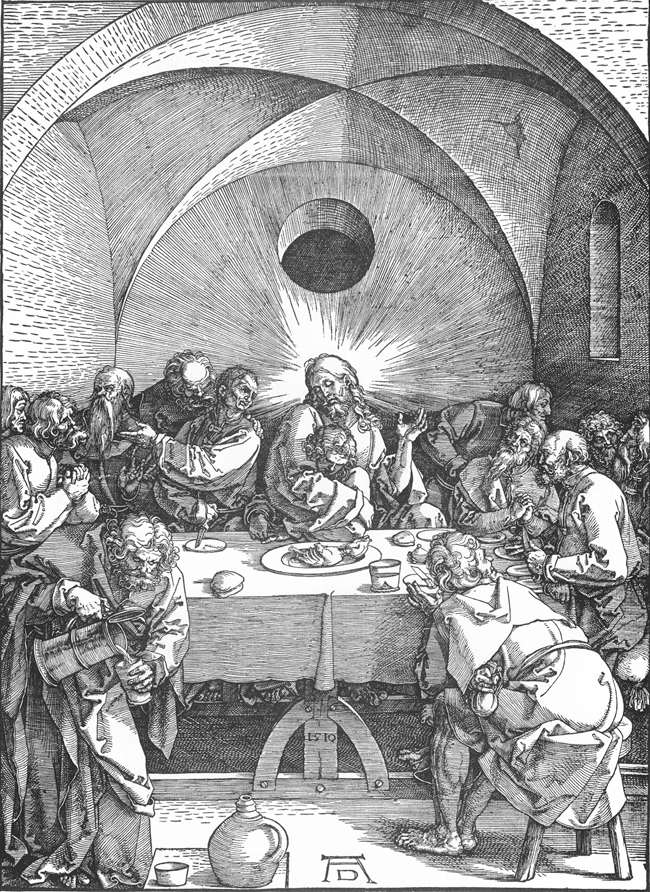

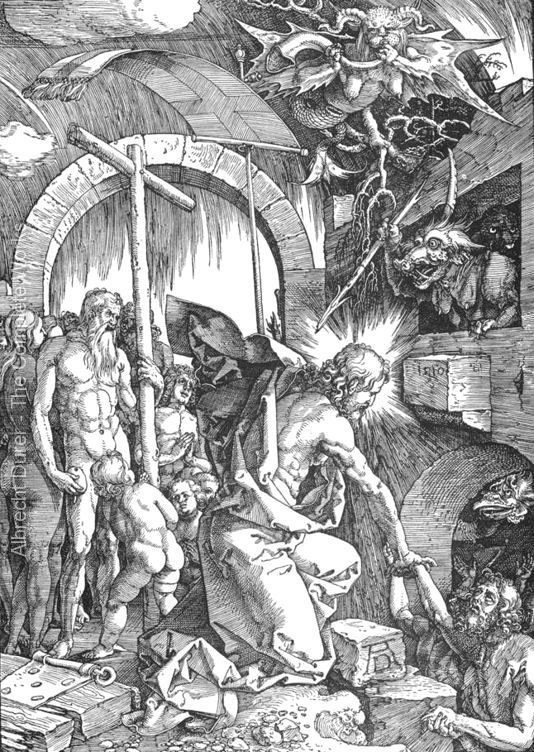

Between the Fury engraved by Caraglio in 1524, that appeared in Rome following the fame of the Florentine Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil engraved by Agostino Veneziano in 1518, and the unfinished majestic Battle of the Romans and the Sabines begun by Caraglio early in 1527 in anticipation of the arrival of the armies of Charles V at the walls of Rome on 6 May 1527, Rosso composed twenty-nine disegni di stampe for one of the most exquisite collections of engravings ever made.1

Rosso was thirty-three when he fled the Sack probably when it reached a short reprieve during an outbreak of the plague in July that could have allowed Rosso to escape, meaning to reach Borgo Sansepolcre where Bishop Tournabuoi would receive him.

His stay in Rome had lasted a little over three years and had ended with as full an understanding of the possibilities of Roman art as that possessed by any of his contemporaries. The nature of that understanding, complete as it was, did not, however, require a full identification with it. Even as points were made in his art that he could be Michelangelesque or Raphaelesque, or antique in appearance, so, too, did the art show that his inventions were exclusively his own. For throughout his years in Rome the artistic formulations of his immediately preceding years in Florence maintained their value. He went to Rome like other Florentines to seek its benefits and learn from its artistic examples, but unlike others of comparable talent (but like the younger Florentine Perino del Vaga whose young Roman education significantly distinguished his early career from Rosso’s) he stayed because he thought he could and would hold his own against the authority of its art and its artistic milieu. In Florence he had learned by necessity to modify his unusual thoughts and feelings into what seem to have been acceptable but still very individual modes of expression. In Rome his abilities, both of self-evaluation and of accommodation, allowed the Romanization of his art, but prevented at the same time his complete surrender to the social manners and the artistic manners of that city. In several ways this Romanization was the maturation of manners of expression that had been well founded in Florence. In Rome he lost his first big commission and never recovered his reputation to those whose patronage might have offered significant success. Designing prints became his major occupation and the source of his income, and created fame beyond Rome and Italy.

PERUGIA

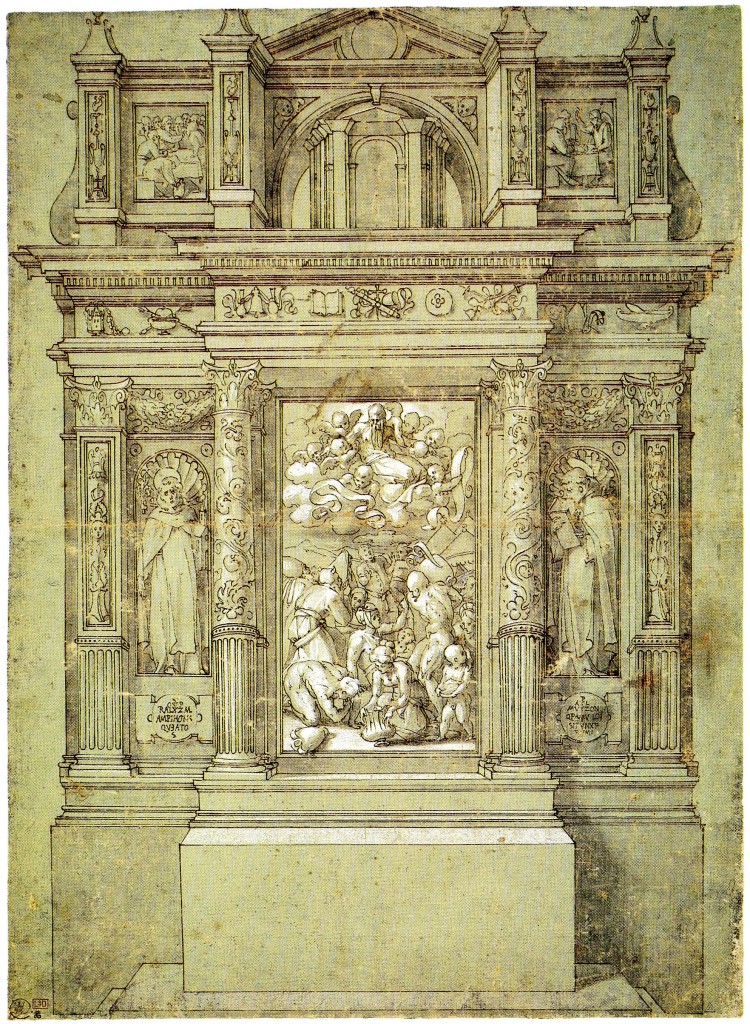

From Rome he first found his way to Perugia, a journey of about 170 kilometers. There he was cared for by Domenico Alfani whom he thanked by making “un cartone di una tavola de’ Magi”, the first of several works Rosso would do in the next three years for artists who gave him their help and their commissions. With many alternations the cartoon for Alfani was originally intended for the Adoration of the Magi formerly on the high altar of the Madonna dei Miracoli at Castel Rigone [Center in text medium size Fig.Alfani AS UNDER E.1].2

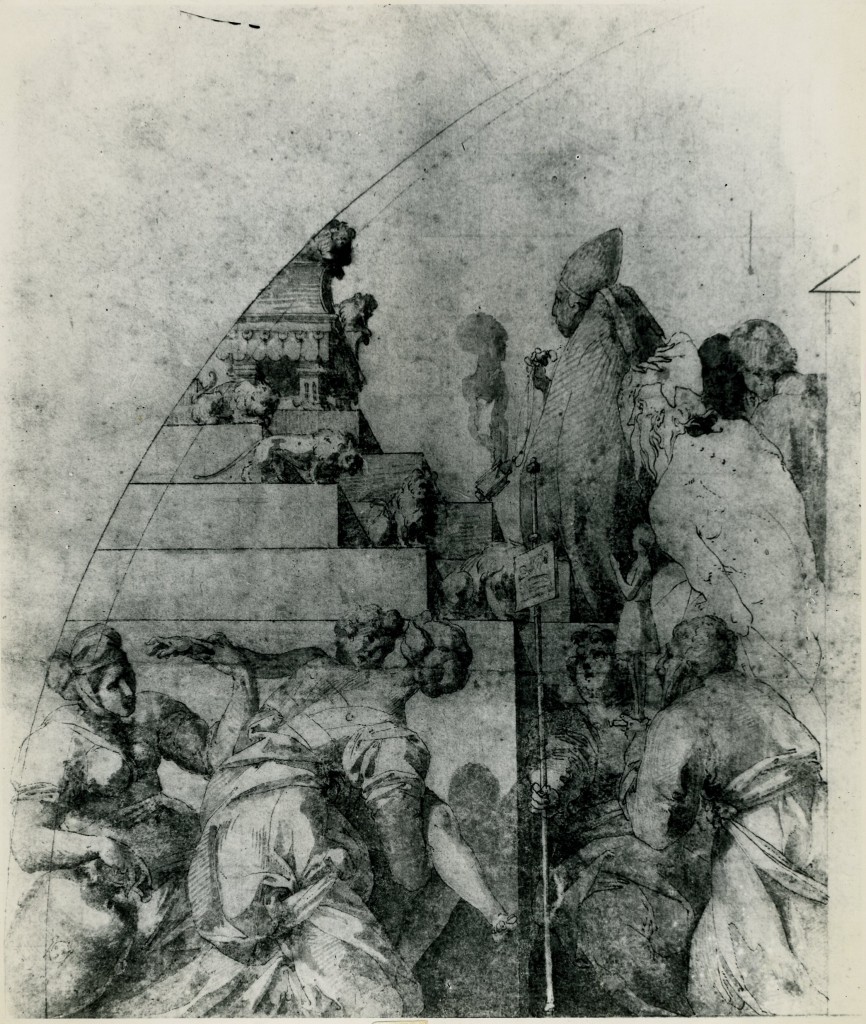

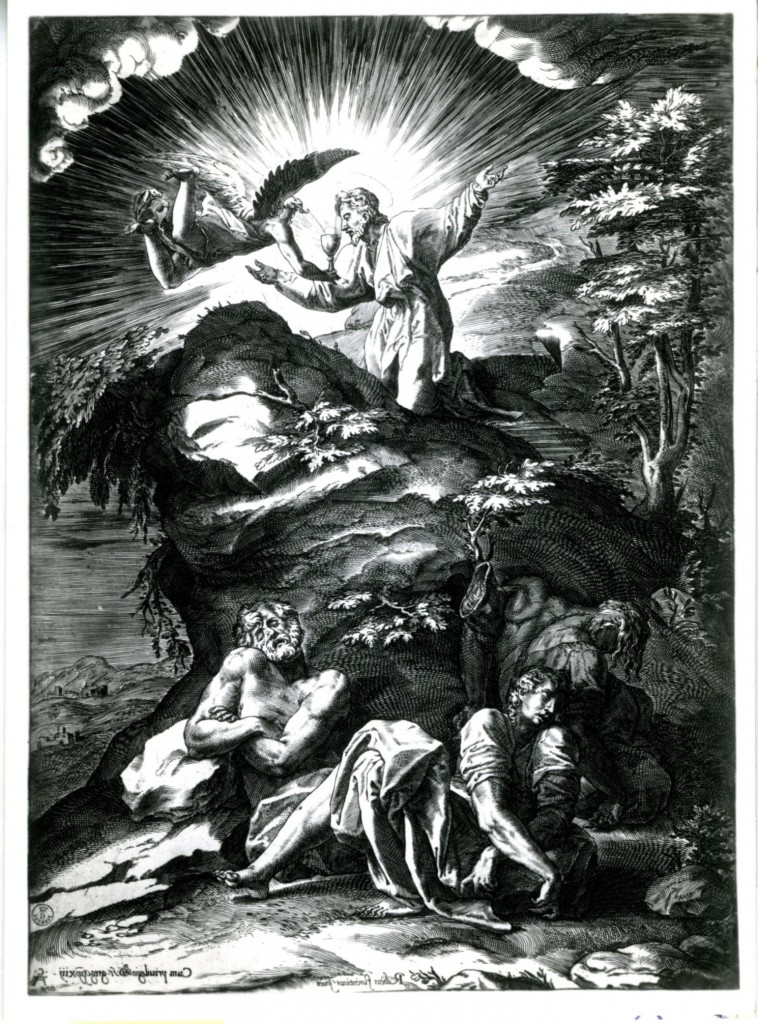

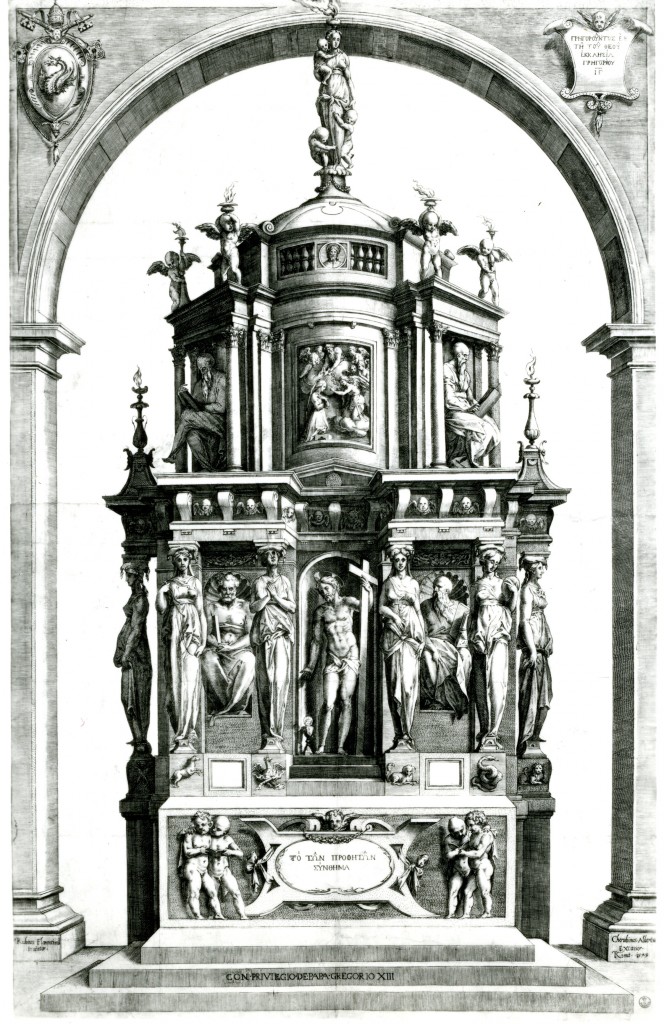

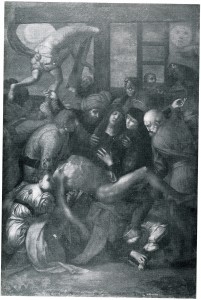

The composition of the lost cartoon is better preserved in an engraving by Cherubino Alberti done in 1574 [Center in text full size Fig.E.1]. Although reversed and likely generalized in small and distant details from what appeared in the original cartoon, Alberti’s print seems otherwise to be a good reproduction of Rosso’s design. Most details are specifically identifiable with those in the Marriage of the Virgin of 1523 and the Roman drawings of the life of Saint Roch. The print also seems to contain a couple of portraits.3

This gift to Alfani is one of the most remarkable inventions of Rosso’s career, coming after the years in Rome when he early on lost the opportunity to execute large narrative paintings. It is another of the several works, beginning with the Visitation drawing that he made for Lappoli in Arezzo on his way to Rome, that he continued to make for others in response to the help he received in the recovery of his career after his escape from the Sack of Rome. But he made this pursuit outside of Florence, which it now appears he had abandoned when he left it in 1524.

The number of figures in Rosso’s Adoration, the crowding of them especially at the left, and the disposition of them within a large architectural setting, bring to mind the just preceding Battle of the Romans and the Sabines. But the spatial organization of the Adoration is more closely related to that of the Saint Roch drawings, in particular the Saint Roch visiting the Plague-stricken (Fig.D.14B) with its diagonal open space leading from the foreground to the upper middle distance. In this drawing the woman bending over and seen from behind, derived from Pontormo’s Joseph sold to Potiphar (Fig.Pontormo,Potiphar), resembles the magus deeply bowing before Christ in Rosso’s composition for Alfani. This figure also resembles a magus in Pontormo’s Adoration in the Pitti (Fig.Pontormo,Adoration), a figure, however, that is not seen so much from behind, although somewhat more so than the old kneeling man he, in turn, resembles, in Pontormo’s Joseph in Egypt in London (Fig.Pontormo,Joseph in Egypt). Returning to the Joseph panel, that Rosso seems to have recalled when he did his Saint Roch Distributing his Father’s Worldly Goods (Fig.D.13), we have possibly also the source of the curving staircase in Rosso’s Adoration of the Magi and of the use of architecture to place figures high up in the scene. It is true that Rosso’s Adoration reflects none of the strange spatial relationships of Pontormo’s picture done almost ten years earlier. Instead, such relationships appear, as do similar references in the Saint Roch drawings, to have been reconsidered by a mode of invention that prefers the more normal appearance and relationships of what is described. The result in the Adoration is the most spacious composition of Rosso’s career up to this time. It is possible that both its normal aspect and its concern with space are what Rosso may have thought would please the Umbrian Domenico Alfani. However in painting his own picture from Rosso’s cartoon these characteristics were not especially heeded. This was mainly because the composition of the altarpiece was altered to give the Madonna and Child their central position in honor of the dedication of the church to the Madonna dei Miracoli and because Domenico Alfani’s talents limited his ability to appreciate the grand spatial arrangement of Rosso’s composition which instead the Umbrian artist filled with significantly more figures, including it seems several portraits than can be recognized in Alberti’s engraving.

Nevertheless, Rosso’s Adoration is more deeply understandable as an extension or elaboration of the aesthetic and expression of his Sposalizio of 1523. The Adoration is more complex and its figures may be more continuously plastic—there is no evidence in Alberti’s print of the faceting forms and surfaces in the altarpiece of 1523—but the proportions of the figures, their diversity, and the quiet but poignant drama of the scene, enriched by the light that rakes across it, are very much those of Rosso’s Marriage of the Virgin. Behind the Holy Family the architecture, partly in ruins, probably refers to the Old Testament, as the shed behind the camels at the right indicates the New. The placement of the Child on a raised block as though on an altar and being held reverently by both the Virgin and Saint Joseph, whose importance is almost equal to hers, conveys something of the same sacramental quality as the formality in the Sposalizio, with its extraordinary young and beautiful Joseph. Christ’s outstretched arms suggest his crucifixion. Looking back at Rosso’s Roman works, the Adoration seems hardly Romanized at all. Instead, one experiences what appears more like the enlargement of the possibilities of his Florentine art. In retrospect this seems, after the Loves of the Gods and the Romans and Sabines, a retreat from the demands of Roman art. At the same time, now out of Rome, the Adoration nevertheless reflects Rosso’s respect for the terms of that art as support for the more gentle aspects of his sensibility.4

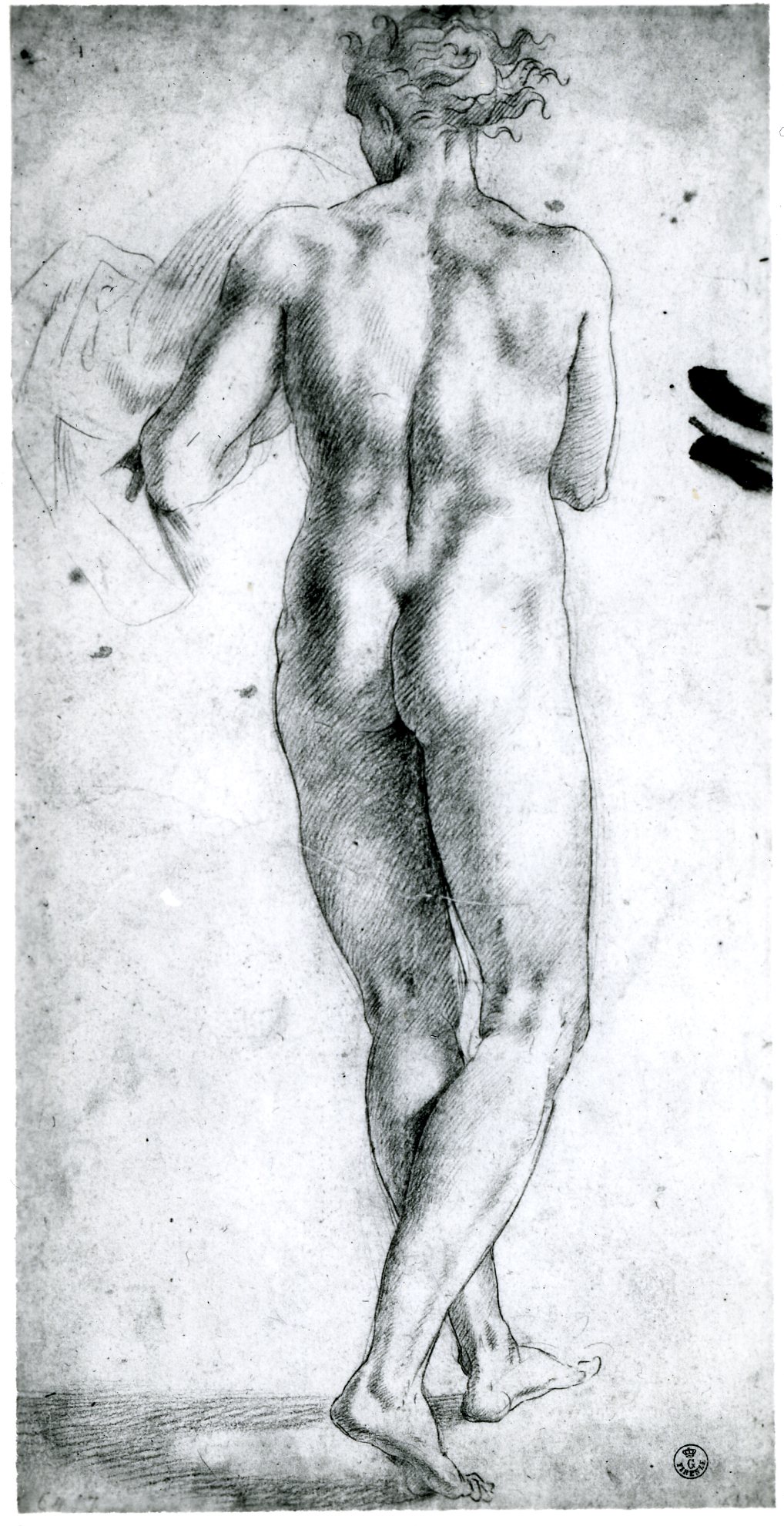

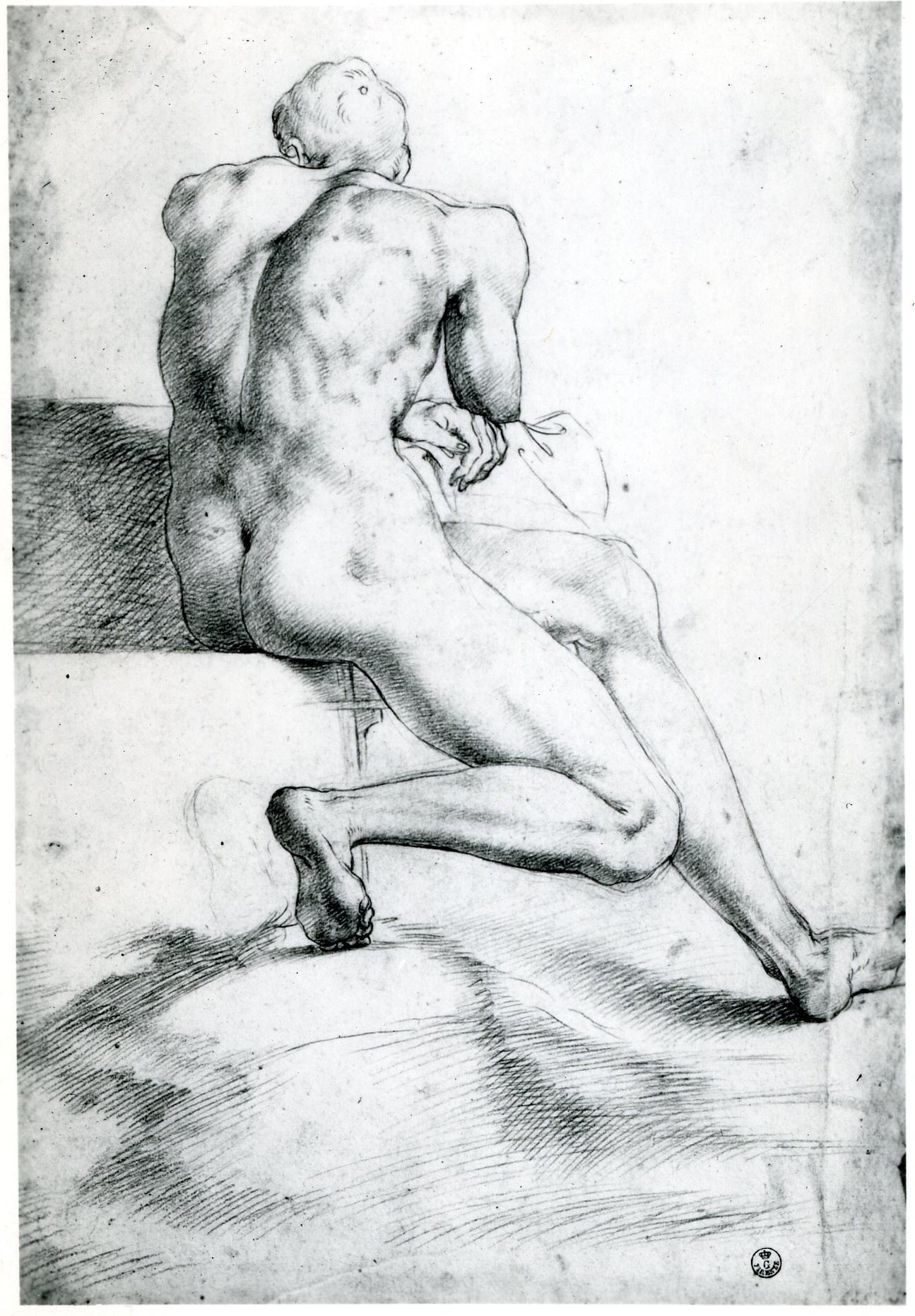

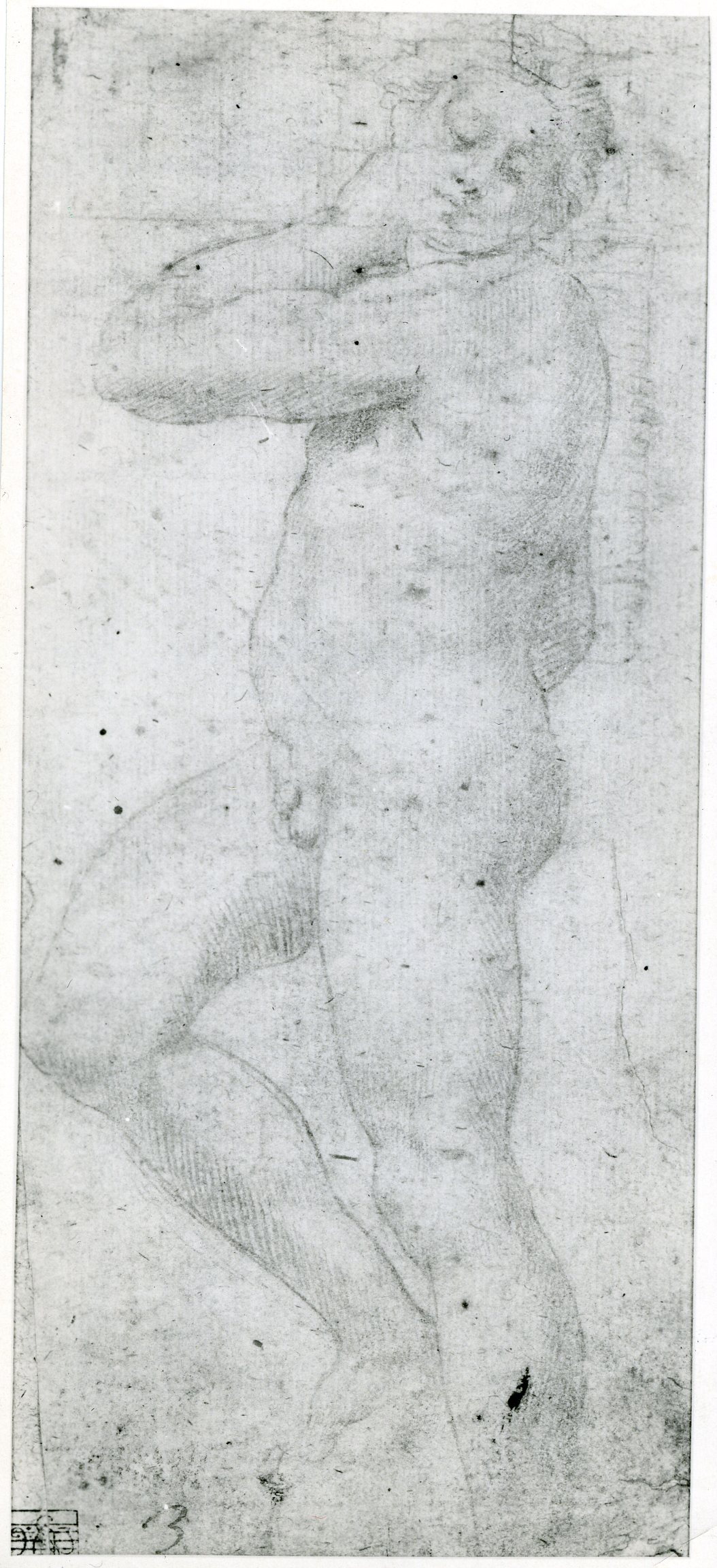

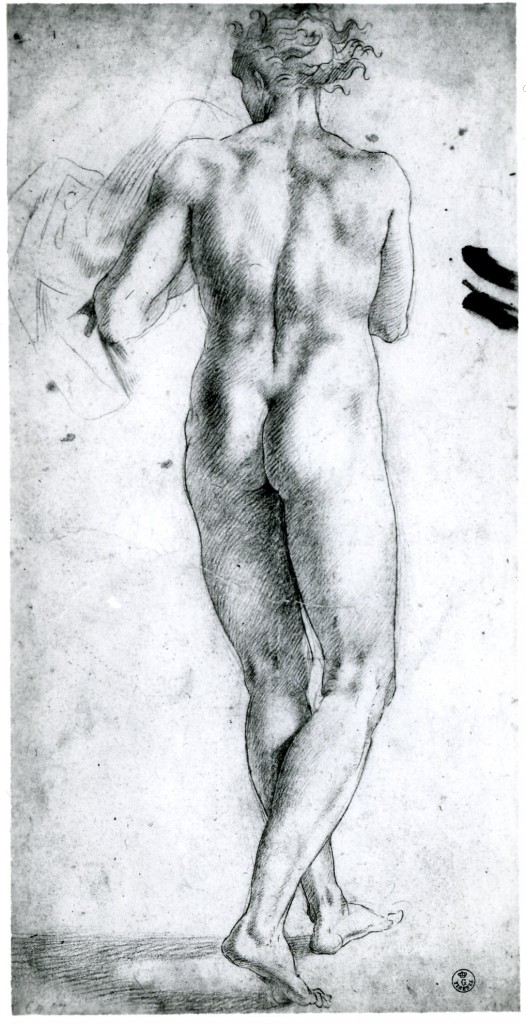

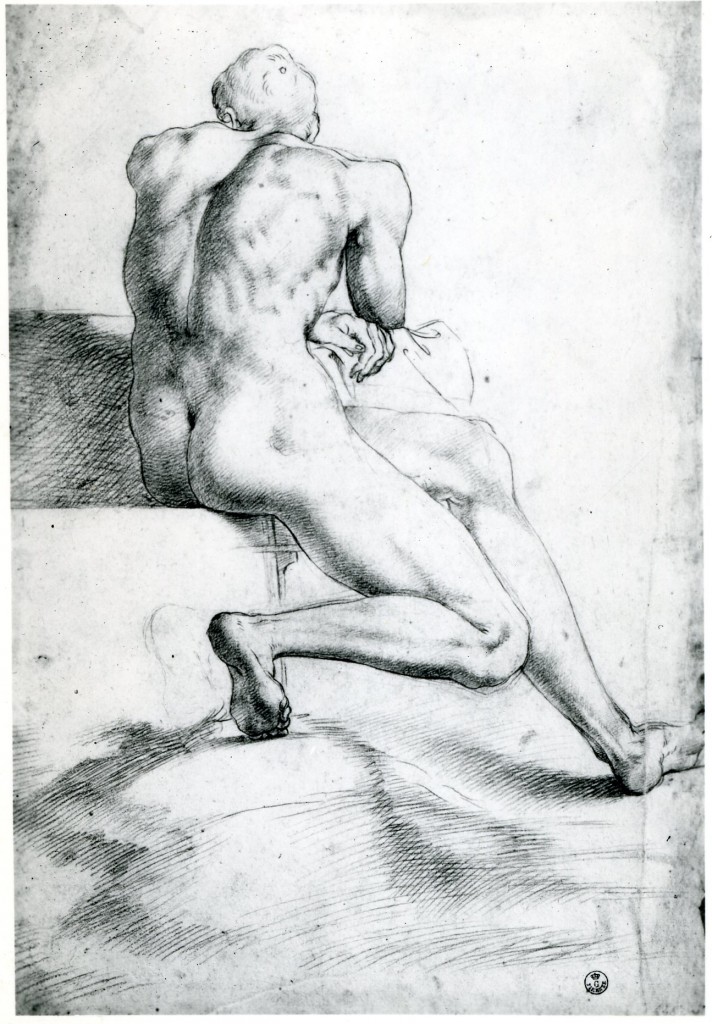

The evidence of two good copies of two lost drawings, the originals probably made as independent nude studies that Rosso was accustomed to make almost every day, as Vasari relates, and then used in the Adoration, also points to Rosso’s reflecting upon the pre-Roman character of his art. Both drawings, in the Uffizi, of nude youths seen from the back, one standing (Fig.D.21) like the clothed young man in the foreground of the Adoration, the other seated (Fig. D.22) like one of the nude figures on top of the building in this composition, are very precisely rendered; the nuances of light and shade on the surfaces of the bodies have been very carefully observed and minutely recorded in a manner that recalls his study for the figure of Saint Sebastian in the Dei Altarpiece of 1522 (Fig.D.7). and the Seated Male Nude of around 1523 (Fig.D.9). While the poses of the two figures of 1527 may suggest the experience of Roman art, the easy bearing of these two nudes presents a relaxation of the strain apparent in so many of the works of the preceding three years. But, insofar as one can judge from these copies, they indicate a certain greater continuousness of light and shade and contour than is the case in the more patchy and static Florentine drawings. This change toward a greater plastic wholeness reflects again, however subtly, an aspect of his art in Rome.

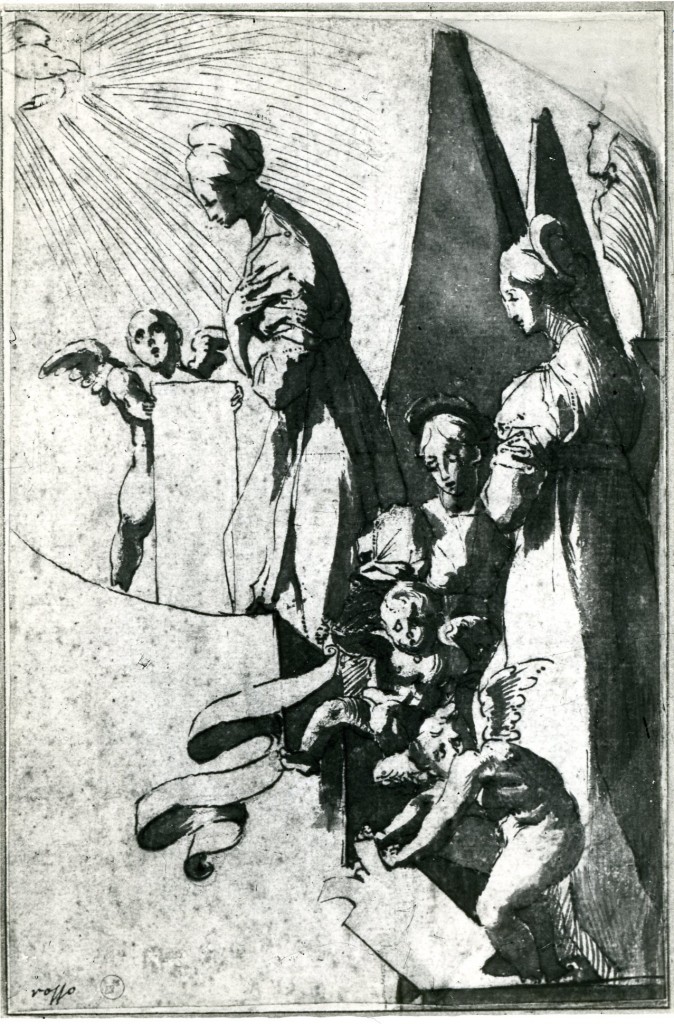

Bishop Saint Resurrecting a Youth

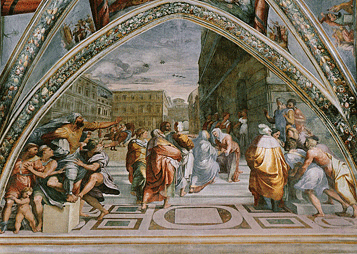

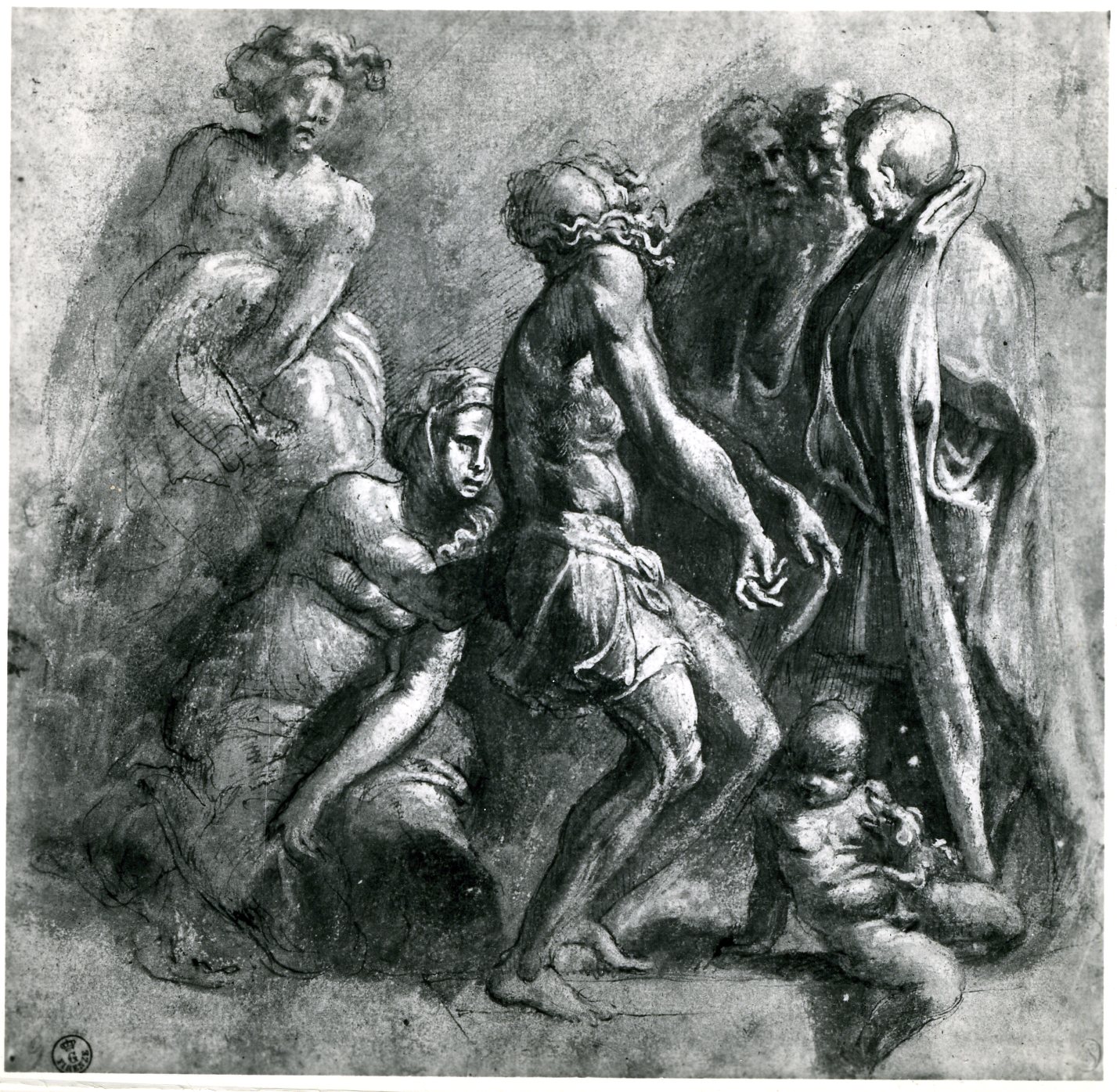

Rosso’s career in the moment immediately following his flight from Rome is likely illustrated further by a drawing in the Louvre, possibly a damaged original than a fine copy of a lost drawing, for what could have been a fresco project for the back wall of a chapel surrounding its altar and what seems to be the profile of a small tabernacle. The composition of this scene, representing a Bishop Saint Resuscitating a Youth [Center in color Fig.D.23], with its asymmetrically placed architecture and loose arrangement of figures around a central diagonal projected back into space, resembles that of the Adoration, with which it shares also the same kinds of varied but in general normal appearing figures. The miracle scene is less spacious than the Adoration with the façade simply a planar backdrop, and the arrangement of its figures tends toward a slightly greater symmetry and formality, but these differences do not suggest a different artistic mode. Instead, one recognizes in these two compositions the extent to which Rosso brought back to mind the possibilities of the clear Florentine narrative art he knew before he went to Rome. His recollections are not in the nature of precise borrowings but the Bishop Saint Resuscitating a Youth reminds one, nevertheless, of the frescoes of Sarto and Franciabigio at SS. Annunziata. Rosso’s figures are more robust and his composition is denser but the effects of quotidian experience that surround the miracle, while not unprecedented in Roman art, as in Peruzzi’s Presentation of the Virgin in S. Maria della Pace (Fig.Peruzzi,Pace) appear more Florentine as recollections. Where these effects resemble aspects of Perino’s Roman frescoes (Fig.Perino,Visitation) they do so because both are Florentine in origin. Like the Adoration drawing for Domenico Alfani, the Lourve drawing may have been made for another artist to execute and Rosso’s drawing may in its clear narrative mode accommodate its style to this circumstance, perhaps still in Perugia where two of its three patron saints were bishops.

BORGO SANSEPOLCRO

Pietà

The composition of the Bishop Saint Resuscitating a Youth in the Louvre presents several similarities with Rosso’s Pietà in Borgo Sansepolcro, commissioned 23 September 1527 and probably completed by March of the following year [Fig.P.19a]. Rosso went to Borgo Sansepolcro probably in the late summer of 1527 to join Bishop Tornabuoni, for whom he had painted in Rome the Dead Christ in Boston. Given the similarity of the Louvre drawing to the Adoration designed for Alfani and to Rosso’s Pietà, it seems likely that the Bishop Saint resuscitating a Youth was done just a short while before the compositionally similar Pietà. But whereas the miracle scene is reasonably clear, formally and narratively, the Pietà appears extraordinarily complex, more so than any earlier work by Rosso.

The commission of this altarpiece for Santa Croce, compagnia di Battuti, according to Vasari, had been given for a small price to Raffaello da Colle, who, out of affection, now refused it wishing that it be given to Rosso so that a work by him would be in Borgo Sansepolcro. Here, however, it was not a matter of Rosso making a drawing that would be executed as an altarpiece by Raffaello, but a work solely by the newly arrived artist. Rosso was not, as with Alfani in Perugia, conceiving an altarpiece to accommodate another artist and his ambiance. Vasari named the altarpiece a Descent from the Cross as details in the background indicate, but the deeply pathetic appearance of Christ’s stretched out dark lavender body on the lap of the collapsed Virgin is what the worshiper first experiences as a Pietà. However it is in the moment in which Christ is still separated from his Mother to bear alone the meaning of the Eucharist. The Virgin, with long outstretched arms, the right arm held up at the wrist by Joseph of Arimathea wearing a bright red turban, his left arm in a black sleeve crossing his body and holding her arm lower down. The Virgin’s other is arm isolated in the dark at the far right behind the head of Saint John but is supported by Saint Scholastica, the twin sister of Saint Benedict,5 and one of the Maries whose left hand is pressed against the torso of the Mother of Christ. The Virgin’s arms are difficult to discover but are forcibly held back within the crowd of figures so that she cannot touch her Son, suggesting at first glance that Christ’s body is being taken from her lap. In the very center of the dark background rises the empty cross with extraordinarily wide horizontal arms, the top edges of which are not visible, hence suggesting a Tau cross as in the Deposition in Volterra. There, however, the chapel in which this painting was placed was dedicated to the Holy Cross. In Borgo Sansepolcro, the dedication was to the Corpus Christi and the cross was more darkly presented leaving Christ’s body as the primary focus of the altarpiece.

In its complexity it is not merely that the picture is dark “per avere osservato ne’ colori un certo che tenebroso, per lo eclisse che fu nella morte di Cristo,” but that the parts of the picture appear so tangled, even illegible such as that extended arm in black, the details so rich, and the highlights so scattered. It is true that there is much in the Pietà that recalls the Sposalizio of 1523, but that picture is largely legible (but for the crowd scenes in the shadowed background) as the later work is not. No earlier picture by Rosso is so complicated as this Pietà.

There is a figural denseness in the lower half of the Romans and Sabines composition but the compression of the forms and the spatial obscurities of the Pietà are not only so much greater than in the Roman composition, they also seem to rise from quite different aesthetic and expressive intentions. Suggestions for many of the elements in this altarpiece can be found throughout Rosso’s earlier oeuvre, from the Assumption at the Annunziata until after his flight from Rome. It is, therefore, possible also to see the Pietà of 1527–1528 as a composite of a large number of the terms of his earlier works brought together here to achieve, by their accumulation, a new kind of aesthetic and emotional significance.

It is likely that the impulse to shape a new artistic mode in the Pietà was stimulated by a visit to his native city from which he had been absent for over three years. We know from a document of 22 January 1528 (DOC. 11) that Rosso, in Borgo Sansepolcro, employed a Florentine attorney for any legal issues that might arise in Florence and elsewhere, suggesting, if nothing else, that he had recently the need to make arrangements in Florence.6 There is, furthermore, a drawing attributable to him done from Michelangelo’s David-Apollo [Fig.D.24] that could only have been executed in front of Michelangelo’s statue. The attribution of this drawing and the date of Michelangelo’s statue are controversial. But the point of view from which this statue was drawn has created an image the planarity of which across the viewer’s line of sight resembles the general disposition of forms in the Sansepolcro Pietà, and the handling of the drawing strongly indicates Rosso. It is likely also that Rosso’s Ideal Bust of a Woman in New York [Fig.D.25a] was done at this same time in Florence directly under the influence again of Michelangelo’s teste divine drawings7 or immediately thereafter in Sansepolcro when Rosso was working on the Pietà. The character of this head and the draftsmanship of it suggest that Rosso had access to Michelangelo’s drawings. The David-Apollo drawing would indicate that Rosso had access to his studio. It should also be recalled that Rosso’s pen drawing in the Albertina [Fig.D.26A] for the figure of Christ in the Sansepolcro Pietà is sufficiently Michelangelesque to have been seriously considered for a long time to be by Michelangelo himself. There is no earlier drawing by Rosso that appears as imitative of Michelangelo. Only the contemporary Ideal Bust of a Woman in New York appears comparably inspired, though by a different aspect of Michelangelo’s art.

While the pose of the figure of Christ in Rosso’s painting recalls Michelangelo’s Christ of his Pietà in Saint Peter’s,8 the emphasis on the anatomy of Rosso’s figure seems to owe more to the nudes of the Medici Chapel. The out spread pose of Rosso’s Christ recalls the Evening and Dawn. An imitation of these figures certainly is not to be recognized, but the significance of Christ’s body as conceived by Rosso in terms of an explicit description of its physical appearance resembles that aspect of Michelangelo’s Florentine figures more than the graceful body of Christ in Rome. In Rosso’s own art, such explicitness had been the case in many of his Roman works, and to some extent also, though more abstractly, in his Moses and Eliezer. The torso of the nude at the lower right of the latter painting resembles in fact Christ’s in Rosso’s Pietà altarpiece of 1527–1528. There is, however, a distinction here between the Sansepolcro Christ by Rosso and most of his earlier nude figures, including the nude Christ in his Roman Dead Christ: Christ’s anatomy in the Sansepolcro altarpiece, while carefully observed and finely described, appears objectified to an extent that almost prevents a sympathetic emotional response to it. The figures in his Disputation of 1517 come to mind. But there is also present something of the forbidding physicalness of Michelangelo’s Medici allegories. It is possible that both the appearance of Rosso’s Christ and the grand drama of his Pietà are also inspired by the grandness and the ethos of Michelangelo’s art. A wilfulness in the style of Rosso’s Pietà even suggests a response to the challenge of Michelangelo’s art, even though in Borgo Sansepolcro Rosso’s reaction would not have been recognized by many beyond Sansepolcro as an aspect of this achievement. Something similar had also been the situation in Volterra in 1521.

If Rosso’s picture is inspired by the grandness of Michelangelo’s art, it is simultaneously influenced by the small and exquisite ornament of his teste divine drawings. While in Michelangelo’s art fine detail is held in equilibrium with the large forms of his figures, in Rosso’s painting one senses an equivocal relationship between them. The skin-tight garment worn by the young man at the left in the Pietà, that recalls the garments worn by the men in Pontormo’s Entombment at S. Felicita of around 1526–1527 [Fig.Pontormo,Deposition], is, unlike Pontormo’s garments, covered with a pattern that tends to reduce the appearance of wholeness of the body of the figure. In the foreground the women, the posture of the Magdalen at the right resembling that of the simply dressed Magdalen in Fra Bartolommeo’s Pietà in the Pitti (Frate,Pietà), wear such elaborate dresses and have such complicatedly plaited hair that their larger formal significance, as well as their emotional value, are hard to appreciate dramatically. The bright highlights of the picture against a generally dark background, similar to those in Sarto’s slightly earlier and approximately contemporary works in Florence, are so scattered as again to disperse one’s attention from what might have been a more fully illuminated center of interest.

Vasari pointed out, writing at mid-century, how the picture was admired per avare osservato ne’colori un certo che tenebroso, per lo eclisse che fu nella morte di Cristo: per essere stata lavorata con grandissima diligenza. Rosso’s interest in an extaordinary kind of illumination in this Pietà recalls the moonlit Deposition in Volterra. In that picture the planarity of the figures bore, in its abstraction, a complementary relation to the unusual light in the picture. The light in the altarpiece at Borgo Sansepolcro is even more unusual. But the fine execution of the details in the picture, which belongs to the second part of Vasari’s praise, does not appear, in its brittle precision, to create a kind of equivalent to the strange illumination. Instead, in their artificiality, the details seem distant from any kind of natural phenomenon at all. On the one hand the painting effects one by its artificiality, on the other by its optical veracity to nature, which should be mutually exclusive. Here, however, they co-exist in a tense alliance with each other.

Looking back to the Volterra Deposition of 1521, details of which re-appear in the Sansepolcro altarpiece, it must strike the spectator how direct is the emotion of the earlier painting and how oblique, restrained, and concealed is that of the later altarpiece. In the Deposition the forms, while not large, are broadly and simply defined, in the Pietà everything is particularized. But this particularization instead of appearing, as it does in the Sposalizio of 1523, derived from the ways things can actually look when illuminated in a special way, is now of a kind that resembles finely wrought jewelry, such as that worn on the back of the woman at the lower left. The glittering details in the general darkness of the Pietà enhance its gem-like character, as does also the extraordinarily rich coloring of the picture. Unlike the Volterra Deposition, the Sansepolcro Pietà must be slowly observed, slowly discovered, and gradually absorbed as a presentation of the Christ as the Eucharist. Each detail complements another, their effect accumulating reciprocally around the head of the Virgin, and in sequences that move both inward and outward. The closed hand of Christ is set against the outspread hand immediately above it that supports the Virgin’s body. The two hands of Santa Scholastica, whose head is, to the viewer, at the right of the Virgin’s, support her under her arms, forming a triangle with the hands of one of the Maries beneath the Virgin’s breasts, but at the same time appearing as the thematic counterparts to the Virgin’s partly closed and raised hands farther out. However, the breadth of the gesture of the Virgin’s outstretched arms is obstructed by the heads of the two men—the one at the right probably Nicodemus9—who support Christ’s body so that it is only after careful investigation that one comes to understand the relationships of these details. At the far left and far right two pairs of hands, one, of a wailing woman, closed and held out, the other more open but placed against the face of the red-haired Saint John—as in the Volterra Deposition—respond, as it were, to the nearby hands of the Virgin. The larger gestures and postures of the figures similarly react across the height and breadth of the picture, and within its depth. As in the Sposalizio the symmetry of the Pietà gives cohesion to its detail. But the planarity of the Pietà and the elaboration of its details affect its symmetry to be less suggestive of actual emotion than of a ritualistic significance. This kind of meaning is part of every part of the altarpiece. It continuously enriches the picture at the same time, however, that it keeps the painting remote from us as the pictorial equivalent of an actual human event. Already in the Moses the emblematic premise of the Sansepolcro Pietà had been unequivocably defined. After his years in Rome the composition of this altarpiece could be even more elaborately and more complexly articulated, and yet also less exclusively as the sole artistic basis of his picture.

While the picture is very dark it is also very colorful but in a manner that lies deeply in the chiaroscuro context of the scene. In a black-and-white photograph the scattered highlights of the altarpiece so dominate that everything else in the picture seems to recede. In front of the picture, however, some of the colors in the shadows penetrate that obscurity to counterbalance the highlights. The large red-orange turban worn by Joseph of Arimathea10 to the viewer’s left of the Virgin is a very bright passage of color equal in its attraction to the light on the face and drapery of Saint Scholastica at the viewer’s right of the Virgin. For this red-orange turban is adjacent to the bright green of his garment and to the deep green dress of the Virgin. Furthermore, the most illuminated portions of the picture are not all brightly white. The drapery of the figure at the upper left is orange in the light, though dark olive-green in the shadow. Other highlighted areas are of colors that are not themselves intense. The youth behind Christ’s head wears a gray-cream garment with a tan pattern. The sleeves of the woman’s dress at the lower left are orange, but this color recedes into the shadow leaving her garment basically a monochromatic bluish green going white in the light and green in the shadows; the length of material falling over her thigh is a dark yellow-brown. The skirt of the Magdalen at the lower right is red-orange, but it is largely in shadow, and though the back of her blouse is yellow-white, the sleeves are gray, with orange bands. There is also a tendency for colors to change to other colors as the forms to which they belong turn from the light into shadow. Consequently, the color of the picture appears to have a kind of contrapuntal relationship to the chiaroscuro at the same time that it supports and is supported by its values. The over-all effects are of “un certo che tenebroso per l’eclisse the fu nella morte di Cristo” and of a circumstance in which a life has been spent.

The altarpiece was painted for the church of the Confraternity of S. Croce in Borgo Sansepolcro, called the Compagnia di Battuti by Vasari. Although a flagellant confraternity and one with a hospital that cared for plague victims,11 it cannot be said that the picture specifically addresses these interests. Christ body, while splayed out and lavender in tone, shows no signs of torture or disease. With the cross and the ladders in the background and one man still on the ladder at the left there are references to the Deposition from the Cross responding to the title of the confraternity and to the subject it requested.

“….on behalf of the said Society and its succeeding members, they [i.e., the officials listed previously] have supplied and leased a painting workshop and panel belonging to the said Society, which should be painted to decorate the larger altar of the aforesaid place, to Master Rubeo Iacopi Gasparis of the city of Florence, painter, respectfully present and receiving on contract, on his own behalf and that of his heirs, etc., the aforesaid panel for the said Society, for the purpose of painting it and creating a noble and appropriate picture. In the painting on this panel he should respectfully paint the body or image of our Lord, that is, when it was taken down from the Cross, together with other figures and forms that arrive and take part in the mystery and the aforesaid deposition, and the whole mystery should be painted with fine colors and other appropriate decorations.[fol. 182r]”12

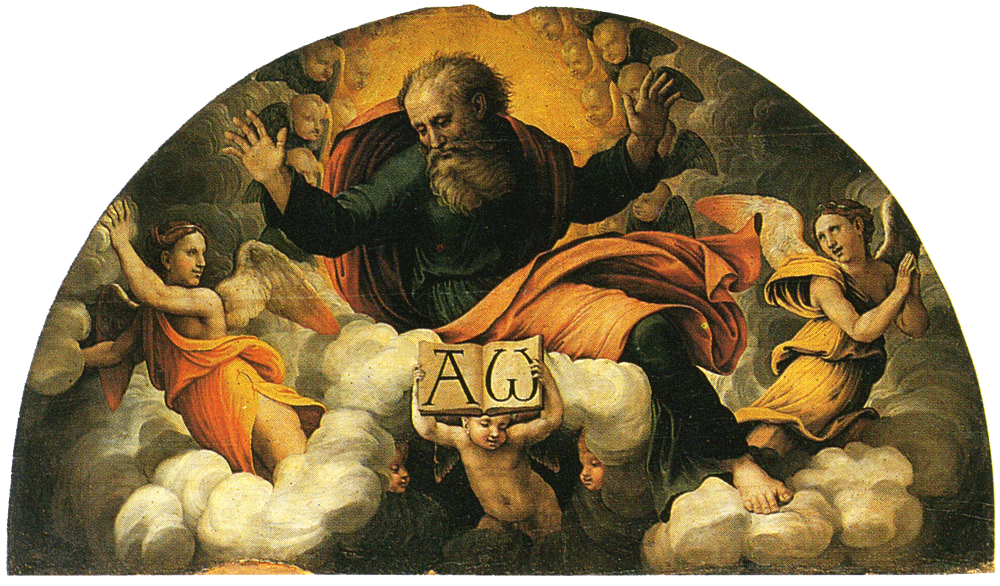

The suggestion of a Deposition is also made by the support of Christ by two men at his head and foot who would have just lowered him upon the Virgin’s lap although the body, at once heavy in appearance and weightless at the same time, as yet barely touches her legs. The men who carry Christ seem not to strain against their load. The Virgin does not hold him as her arms are flung back in a gesture that tells of her agony and seems to reflect Christ’s arms on the cross, the horizontal bar of which is visible above her. She is dressed in green rather than the traditional blue, referring probably to the green of the cross on the garment worn by the members of the Confraternity of S. Croce.13 In the background and slightly to the right of center is a hideous figure with a spear resting on one shoulder and a shield held up at his other side. He has no nose, his eyes are crossed, and his mouth bears an expression, with the teeth visible, that could be interpreted as a cruel smile. His shield and spear would seem to indicate that he is one of the executioners. But the physiognomy that Rosso has given this figure is not required for the description of a Roman soldier. This figure may represent Satan whose ultimate success would seem to have been achieved with the death of Christ. The emphatically deathly depiction of Christ’s body, so unlike that in his earlier pictures in Volterra and Boston, reinforces, in an almost macabre manner, the finality of Christ’s life. But above Rosso’s altarpiece in a lunette [Fig.Raffaellino del Colle, God-the-Father and Angels AS IN P.19 AND PLACED ABOVE A FIG. OF ANOTHER IMAGE OF THE PIETÀ] painted by Raffaellino del Colle who had ceded the commission of the Pietà to Rosso when he came to Borgo Sansepolcro—”acciochè in quella città rimanesse qualche reliquia di suo“—there is a full-length figure of God the-Father looking down toward Christ. Beneath him is an angel holding open a book that bears a large alpha and a large omega. The design of this lunette, which is similar to that above Raffaellino’s Annunciation in the Pinacoteca in Città di Castello,14 is clearly Raffaellino’s and was either made to fit with Rosso’s picture or belongs to Raffaellino’s original commission, the subject and size of which Rosso had to accept, along with the newly designed altar and choir to which it belonged, that included the frame of the picture and its lunette, one would suppose. For if the devil of Rosso’s painting is about his supposed victory, the message of the lunette reveals to the worshipper the falseness of that supposition.15 The role of this startling figure in the Sansepolcro altarpiece is not unlike that of the young and handsome Saint Joseph in the Sposalizio of 1523. The youth of this bridegroom, as mentioned before, may have been intended to deceive the devil as to the paternity of Mary’s forthcoming child. A comparable kind of deception may be meant in the later Pietà, and therefore there may also be intended a meaning related, tangentially, to that of the Disputation of 1517. What is presented, in other words, is a significance that is by intention oblique and obscure, requiring for discovery an investigation into the appearance of things that tends to remove one from a too immediate experience of visual and emotional values. This had already been an aspect of Rosso’s somewhat difficult to comprehend Assumption of 1513–1514.

In several respects the Pietà reflects knowledge of Pontormo’s Deposition in S. Felicita in Florence at the same time that Rosso’s painting is conceived in fundamentally different stylistic terms [PAIR Fig.P.19a and Pontormo, Deposition]. The skintight garment of the young man at the left is new to Rosso’s art but is found, though undecorated, in Pontormo’s altarpiece. More important, however, is what appears to be a kind of correspondence in these two pictures, in spite of their slightly different subjects, of the thematic relationship between the Virgin and Christ’s body and between them and the attendant figures. One group of figures cares for and attends to Christ’s body; another group supports the swooning Virgin. Through this separation the figure of Christ, though still associated with the Virgin’s sorrow, maintains also an autonomous value for the spectator. Placed above the altar immediately before one at mass, that body is for the spectator the Corpus Christi of the Eucharist, that Corpus sive immago Domini nostri that the altarpiece was to honor. Here there is a similarity to the Roman Dead Christ, painted for Leonardo Tornabuoni, the bishop of Borgo Sansepoclcro, who would seem to have been influential upon Rosso receiving the confraternity’s commission, and who had a special interest in the Eucharist, in the administration of the sacraments, and in lay fraternities.16 But in the differences of the presentation of Christ’s body to us we can begin to know the almost opposite attitudes of Pontormo and Rosso. In the S. Felicita Deposition Christ’s body is brought toward us, to the altar;17 in Rosso’s Pietà the body is inert and stretched out in front of us, above the altar for this moment of the drama. Its forms are particularized and angular. Pontormo’s Christ is supple, even sensual, and appears as though he could be merely asleep. This too had been his appearance in Rosso’s Deposition of 1521. But in the Pietà he is decidedly dead. Pontormo’s figures are broadly and consistently rotund and they are so turned within the composition as to generate a sense of all-pervading feeling of numbness and of a suspension of actual mass by the figures’ grief.

Several of the major figures in Rosso’s altarpiece are seen in profile and almost all are so clearly balanced one across from the other such that the scene appears static and emblematic rather than immediately moving. The complicatedness and darkness of the Pietà are also opposed to the clarity of Pontormo’s Deposition. It is as though the two pictures presented two poles of artistic expression in Tuscany in the middle of the 152os. This is not wholly true only because Rosso’s picture is to some extent dependent upon Pontormo’s, but because they both also share an interest, albeit of different kinds, in Michelangelo’s art. Furthermore, there is the relationship of Rosso’s picture to Sarto’s contemporary style with its steadfast adherence to the terms of his earlier art carried to a point that might almost be considered dogmatic. While this aspect of Sarto’s art, as represented by the Gambassi Altar [Fig.Gambassi Altar] and the Passerini Assunta [Fig.Passerini Assunta MAKE A PAIR OF THESE TWO PAINTINGS], is not obviously related to Pontormo’s, it is reflected in Rosso’s. The Sansepolcro Pietà has the severe symmetry and hard brilliance of Sarto’s paintings but at the same time it exhibits remarkable elaborations upon them. The extent to which these elaborations carry Rosso’s image beyond Andrea’s matter-of-factness can be identified with the extraordinariness of Pontormo’s Deposition. But Pontormo’s expression is deeply about human feeling, suffering, loss; Rosso’s largely is not. For him there is a kind of meaning that is other than that conveyed by the representation of emotion alone. There is the fact of death itself, and in his Pietà, the ritualistic attendance to it. In the background of this scene, immediately to the left of the cross, appears Rosso himself [Fig.P.19e,Pietà,Self-portrait ADD ALSO TO CAT. P.19] 18 as Pontormo appears in his altarpiece in S. Felicita. Also, Rosso’s Christ has bright red hair and beard, brighter than in the Volterra Deposition. Although the appearance of Christ with reddish hair is not uniquely Rosso’s conception, the degree to which it is red in this picture is unusual. One cannot avoid the suggestion, made also by Darragon in 1983, that Rosso identified himself with his dead Christ.

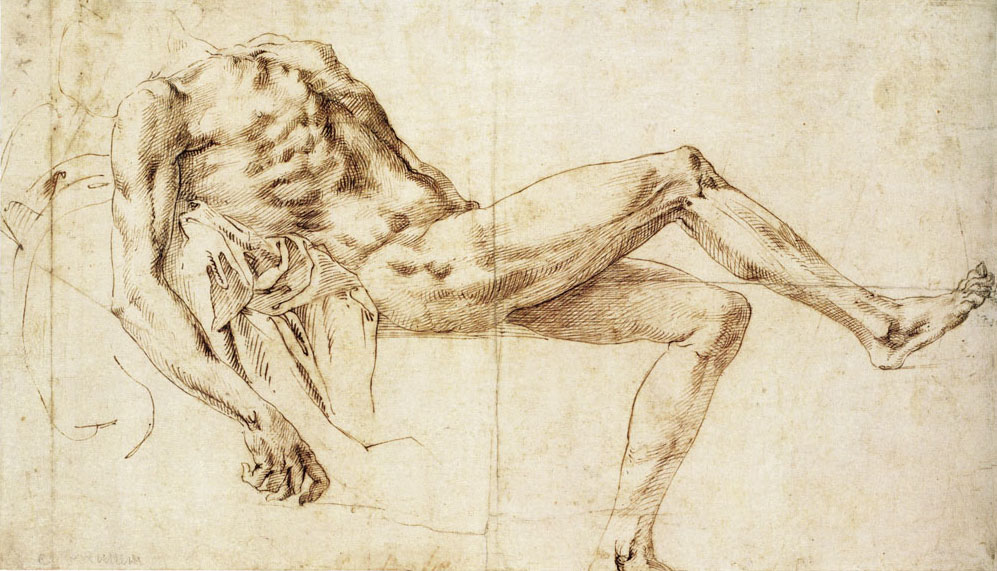

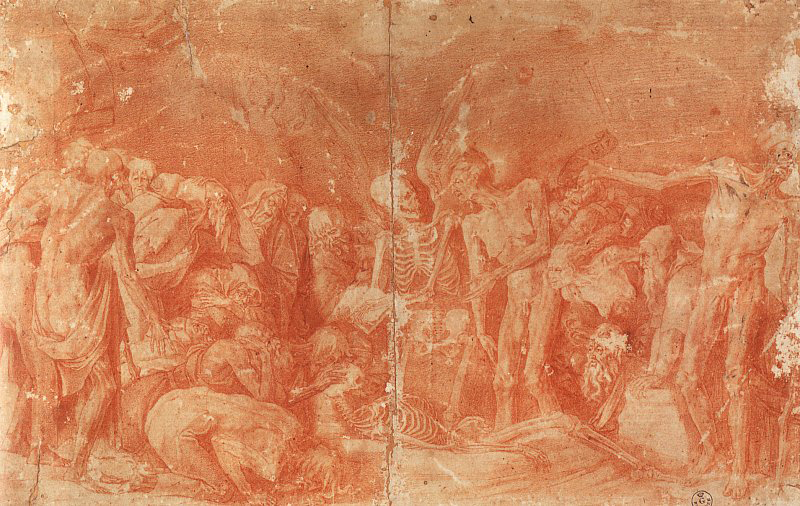

The Michelangelesque pen drawing in the Albertina for the figure of Christ in the Borgo Sanspolcro altarpiece [CENTER Fig.D.26 REPLACE IN COLOR] was carefully drawn from life and from a slender, broad-chested model of a type frequently found in Rosso’s art. His torso and right leg have been propped up, and this pose has been almost exactly repeated in the painting although the body there appears supported by two figures. However, the placement of the old man’s hand under Christ’s right thigh in the painting seems little more than a gesture. For the right leg of Christ seems to have no weight, and the fall of the lower half of the leg does not accord with the support described in the painting. Consequently, while the figure from one aspect looks explicitly realistic, from another, in terms of its functioning as a dead body, it is not. The pose in the drawing has been slightly altered in the painting so that the forms are more nearly parallel to each other. Similarly the anatomy of the figure has been regularized from its more natural appearance in the drawing. To some extent the same was true of the transfer of the red chalk drawing of a nude in the Uffizi [Fig.D.7] into the figure of Saint Sebastian of the Dei Altarpiece. But the underlying anatomy of the figure of Christ is emphatically exposed like that of the Roman Fury and it is similarly patterned to make of its realistic data a spectacle that goes beyond mere verisimilitude.19

Given when the Sanspolcro altarpiece was done and the extensive literature on it, only Franklin mentioned the Sack of Rome in relation to Rosso’s painting by commenting that the simian-like soldier holding a shield perhaps personifies the artist’s attitude toward soldiers following his brutal treatment by them during that horrendous catastrophe that the artist has personally experienced. The evil aspect of this figure has often been noted by others but only in relation to the content of the picture. Chastel wrote of the picture in his extensive account of the Sack, and yet without mentioning this monstrous figure: “A simple, almost rudimentary symbolism has been used here to blend a personal view of bereavement or actual melancholy into a traditional and pious representation of death,” writing of all of Rosso’s works of these years as “disjointed and muddled to the point of revealing an uncontrolled nervousness and a strange lack of technique.” This is hardly the only way that the Sansepolcro altarpiece can be experienced as Rosso’s first painting begun only two months after his flight from that hell that Rome had become. And “lack of technique” seems a strange observation of a picture that is masterfully painted.

The scene takes place on Golgotha in a darkness that Vasari noted as the tenebroso of an eclipse of the sun, leaving the light of the moon to shine upon the foreground figures. All the major figures of a deposition are there but the lowering of Christ’s body, that is the event of the Volterra altarpiece, has already taken place and the somber gray-lavender corpse appears at the moment of its placement upon the Virgin’s lap. She has fainted and her arms are held widely open to accommodate her son’s body. Within its gloom the scene becomes remarkably splendid around the dark body, such that the historical narrative is itself displaced by the presentation of Christ’s body, dead but not disfigured, and without the expression that he has in the earlier Deposition. The elaborateness of the costumes and coiffures, the variety of the colors, the fine execution of the details, are all in the service of the presentation of that sacred body and appropriate to the mystery of the deposition that the artist was charged to create. That mystery here approaches the aspect of a relic in a splendid reliquary. It should be recalled that the picture would be set in the design of a new altar and choir, replacing a Crucifix that had been on the high altar.

It is possible that the central image of death and of the collapse of the Virgin, set against the gloom of the background that penetrates the spaces between the closely placed figures in the foreground, in which that monstrous simian face of evil is a detail, is, as the altarpiece it also was, Rosso’s votive to the miracle of his surviving the Sack of Rome. There is no other picture by Rosso that matches the brilliance of this altarpiece until the Pietà in the Lourve [CENTER MEDIUM SIZE Fig.P.23a], painted for the chapel of the Connétable Anne de Montmorency at Écouen, that shows a concentrated recollection of the Sansepolcro painting. The posture of Christ and the depiction of eaglettes on the pillows under him approximate the coat-of-arms of Montmorency that appears several times on the vaults of the chapel, indicating a personal identity with the Connétable. Here, in the Louvre painting, the site is not Golgotha but the area before the cave in which Christ’s body would be placed. Again, however, it is not clear that this body had just been placed on the Virgin’s lap or that it is about to be removed for burial. The open wide and entirely visible arms of the Virgin make both interpretations possible.

Rosso’s Ideal Bust of a Woman in New York [ CENTER LARGE Fig.D.25a] shows the influence of Michelangelo’s teste divine drawings to be largely one of motif than of structure. The kind of headdress with a pair of ram’s horns worn by Rosso’s woman, suggesting that she is Venus, is very similar to that of Michelangelo’s testa divina drawing in the British Museum, the fine but almost impersonal handling of which closely resembles Rosso’s [CENTER MEDIUM SIZE Fig.Michelangelo, Testa Divina].20 The handling of the waves over the forehead is so similar in both drawings as virtually to document Rosso’s closest study of Michelangelo’s drawings. This seems also indicated by the pen drawing in the Albertina for the figure of Christ in the Sanspolcro altarpiece, but there it is the study of another kind of Michelangelo’s draftsmanship. Compared, however, to Michelangelo’s bold and integral conception, Rosso’s ornamental head seems merely the summation of its decorative details. Unlike Michelangelo’s head, Rosso’s Ideal Woman, seen partly from the back but with her head turned slightly forward beyond a strict profile, appears, however anachronistic, merely fashionable and almost coy. The austere richness of Michelangelo’s head has been replaced by what seems more like decoration in Rosso’s art. The head, however, recalls Rosso’s earlier flirtatious Phylira, but hardly at all his Roman Head of a Woman in the Fogg Art Museum.

If the Sansepolcro Pietà presents a dogmatic tightening of Rosso’s style in terms both of the composition of the picture as well as the explicit description of its details, then the next work we have by him indicates a broadening of this manner. It is not an autograph painting nor even a good copy in the ordinary sense. It is rather a damaged but recently finely restored altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi by Giovanni Antonio Lappoli for which Rosso provided the design (L.21), probably early in 1528 when the Aretine artist visited Rosso in Borgo Sansepolcro. The picture was painted for the high altar of the church of S. Francesco in Arezzo.

[CENTER LARGE see COLOR L.21 Fig. Lappoli Magi b]

Except for a few similar motifs, and a similar importance given to Joseph, Lappoli’s Adoration differs significantly from the composition of the same subject that Rosso designed less than a year earlier for Domenico Alfani in Perugia. Lappoli’s picture is not simply a narrative scene, for with the appearance of Saint Francis and Saint Anthony of Padua in the foreground it takes on also something of the character of a sacra conversazione. There is, therefore, a certain correspondence between this altarpiece and Rosso’s Marriage of the Virgin of 1523 as well as his design of Lappoli’s Visitation of 1524 where Mary Magdalen and King David appear in the foreground [CENTER MEDIUM SIZE COLOR Fig.Lappoli,Visitation]. But the later Adoration for Lappoli is much grander and more formal in its conception than is either of these earlier altarpieces. Its greater formality suggests the composition of the Sansepolcro Pietà and yet with significant changes to the plan of that picture. The Pietà is very densely composed with the figures placed very close to each other, both side by side and in layers within the depth of the picture. The Adoration has fewer figures, and also far fewer than in the very fully populated composition designed for Alfani. The figures are relatively widely spaced so that most of them overlap very little, and they are arranged not so much in layers back into space but rather with one figure above the other and matched with its varied counterpart across from it. The figures are broadly defined and although this is undoubtedly partly due to Lappoli’s limited abilities as a painter it also accords with the broader compositional properties of the picture. The two saints in the foreground and the Virgin in the center form a very clear pyramid; the other figures are arranged symmetrically at either side in postures that indicate their roles as magi and attendants. But even the deeply bowed posture of the magus at the right or the reciprocating Child and Joseph to the left do not hinder the large formal effect of the picture. One is reminded of the severe order of Sarto’s approximately contemporary Gambassi Altarpiece. But in the postures and placement of some of the figures and in the degree and ease of variation within its pyramidal formality Rosso’s design also recalls Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi of 1481. Rosso had studied this picture earlier, as shown by his Disputation drawing of 1517, but it is possible that he studied it again in Florence late in 1527. But now Leonardo’s Adoration was not seen so much in terms of the multiplicity of effects within its composition but in terms of the larger components of the design itself.

As with the cartoon for Alfani, that Rosso seems to have used for his drawing for Lappoli, figure studies were made independently of any composition in mind. A copy in Rennes shows very detailed studies of feet and a left hand [Fig.D.26] that were utilized by Rosso for the figure of Saint Francis, giving some idea of how specific the lost drawing for Alfani’s altarpiece was. It is possible that Lappoli also knew Rosso’s other individual studies that were used for this altarpiece drawing.

AREZZO

At some time between late March and 20 April 1528 Rosso went to Arezzo.21 There is some likelihood that this visit was only a stop on another trip to or from Florence, the experiences of which may be reflected in his immediately subsequent works. When he was in Arezzo he met the young Vasari and obtained for him the commission of a Resurrection from the Aretine Canon Lorenzo Gamurrini on 20 April. He also supplied Vasari with a drawing for it that has been lost (L.22), as has Vasari’s painting. While the specific nature of this contact between Rosso and Vasari cannot be judged, there is no doubt that this early work like most of Vasari’s earliest surviving works showed the unmistakable imprint of Rosso’s style.

CITTÀ DI CASTELLO

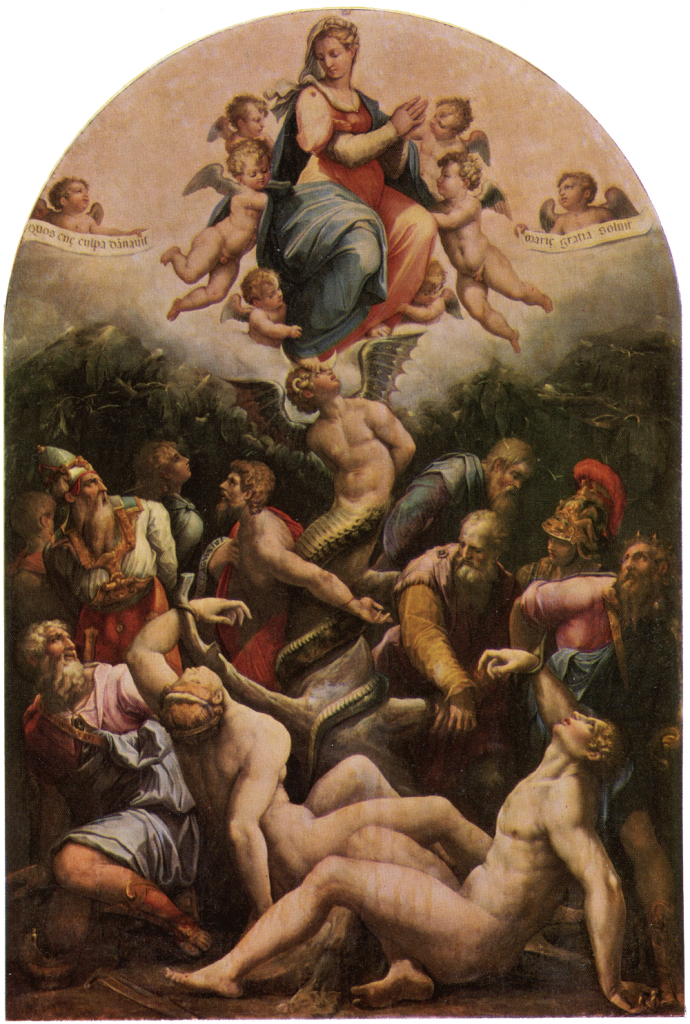

Possibly through the aid of Bishop Leonardo Tornabuoni, who was appointed governor of Città di Castello in 1527, Rosso received on 1 July 1528 the commission for an altarpiece from the Compagnia del Corpus Domini of that city (Fig.P.20a). Not painted until the end of 1529 and the early months of 1530 it was, however, first planned in the summer of 1528 in Città del Castello. From that time three drawings, an original and two copies, indicate that the painting was at first conceived somewhat differently from its final appearance. The evidence of these drawings also suggests very recent contact with Florentine art and a response to it noticeably different from what seems to have been the response earlier in the Sansepolcro Pietà and in the drawings approximately contemporary with that altarpiece.

The contract of 1528 called for an altarpiece con la figura de uno Cristo resuscitato e glorioso con la figura de la Nostra Donna a con la figura de Sancta Anna, con la figura de Sancta Maria Madalena e con la figura de Sancta Maria Emptiana [Egiziaca], a de basso in dicta tavola più e diverse figure che denotino e representino el populo, con quelli Angeli che a lui parera de acomodarre; … Here is prescribed the composition on two levels of the executed painting, as well as the saints and populo that appear there without, however, the Angeli that were requested. Basically the first composition of this altarpiece was the same as that of the finished altarpiece with an upper and lower part, but the postures, disposition and garments of some of the figures were changed, giving to the bottom half of the picture, at least, a slightly less rigid and formal appearance than that of the completed painting. The four female saints at the top seem all to have been originally thought of as less clothed.

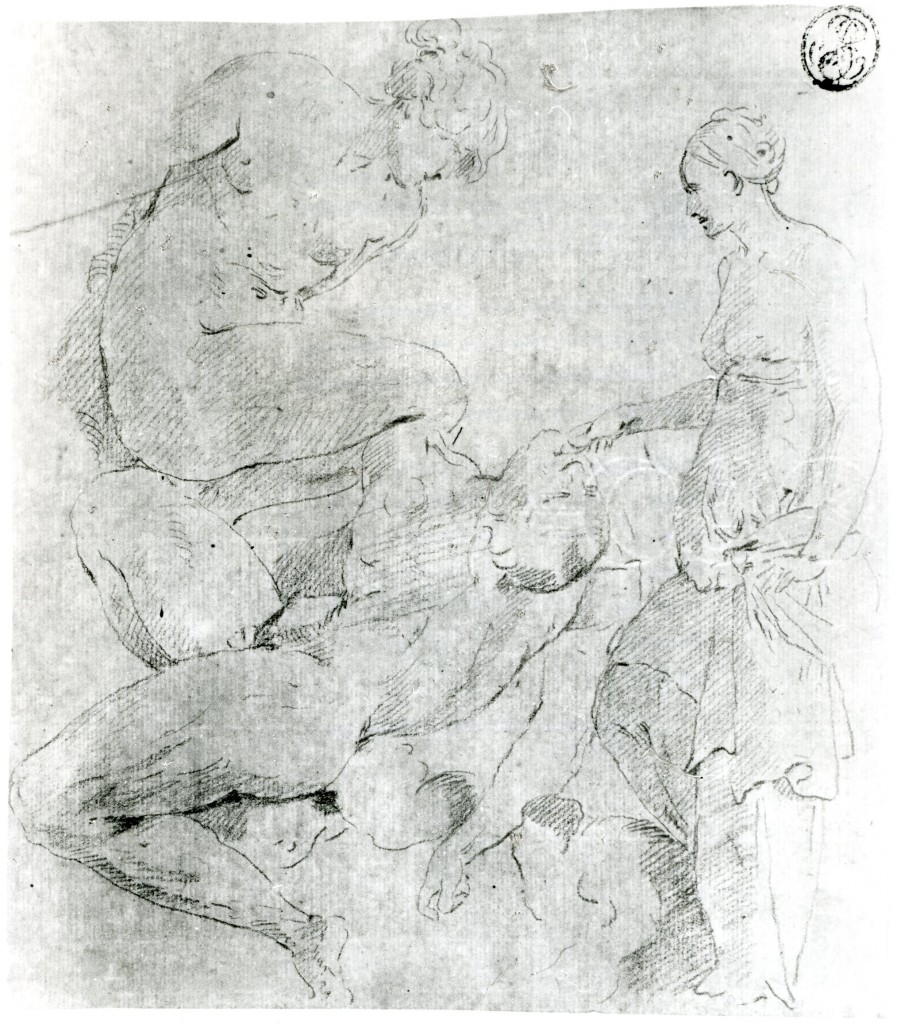

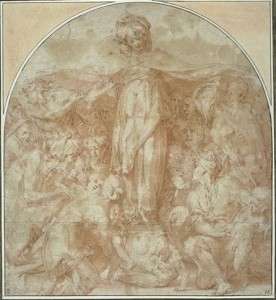

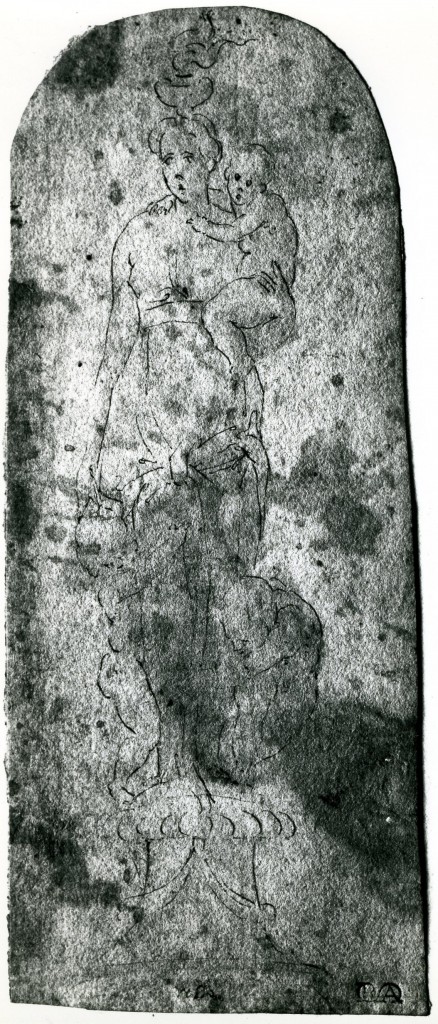

A poor and altered copy of a drawing by Rosso in the Louvre [Center Fig.D.27A] gives his early conception of these four female saints, showing the central two directly facing each other. The space between this pair that would show the figure of the risen Christ has been eliminated (although we do not know the placement of these figures in relationship to Christ in the lost original drawing). While this omission is confusing it is very likely that the drawing is otherwise a fairly accurate record of the appearance of these four women in the lost drawing. Two of the four women, one of them occupying the position of the Virgin in the painting, are nude above the waist. Saint Anne, whose head and shoulders are covered, has bare arms and possibly a bare torso. Only the fourth saint at the far left is amply covered, although her nipples are indicated through her dress. Both of the Virgin’s arms and hands are clearly visible in the drawing while in the painting her left arm is only barely seen and her left hand not at all. The folds of all the drapery of the figures are less complex than in the painting.

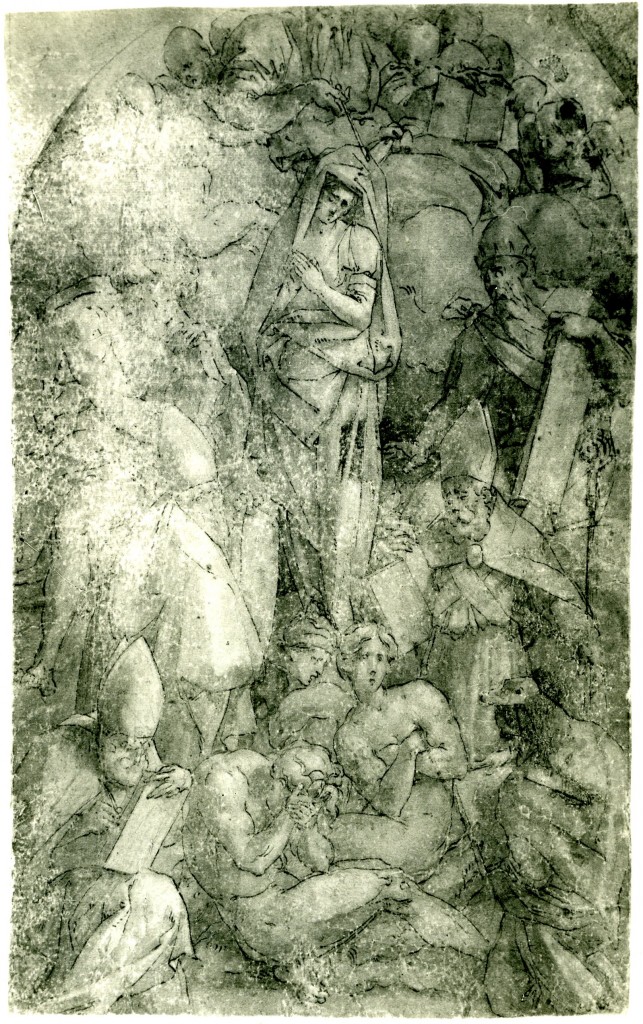

The early composition of the bottom of the picture is represented by two drawings, one a spirited copy in the Uffizi [Fig.D.28], the other a fine drawing in the Gabinetto Nazionale in Rome [Fig.D.29] PLACE THESE TWO IMAGES LARGE ABOVE EACH OTHER IN THE CENTER. The drawing in Florence must copy an earlier drawing, and like the drawing in the Louvre it shows some of the figures less clothed than they are in the painting. The drawing in Rome and the Uffizi drawing indicate that originally the center of the lower scene was conceived to show a seated or kneeling woman facing forward and looking up and gesturing with her right hand toward a man who stands before her. He was turned away from the spectator but with his arms extended toward the viewer and downward in the direction of a child with a dog seated on a step at the lower right. This child and dog are identical, though reversed, to the group at the lower left of the Bishop Resuscitating a Youth. Three men are at the right instead of two as in the altarpiece. At the left is a man, behind the seated women, facing forward and holding a bundle of drapery. He is the figure who wears a helmet in the very center of the finished picture. The drawing in Rome shows the same figures, but only two men at the right and not the man to the left holding a bundle of drapery although a vacant space appears where he could be placed. The standing man in the center is more fully clothed and the position of his arms is slightly changed so that they are not seen directed toward the child, who is here only lightly sketched, but rather toward the viewer. All of the figures are also broader and more robust in appearance. Furthermore, in the drawing in Rome there appears the woman and child at the left who are almost identical to those in the finished altarpiece. This group is similar to one in the foreground of the Romans and Sabines engraving.

From the two drawings in Rome and Florence it is possible to have a rather clear picture of what Rosso originally intended for the lower half of the altarpiece. If the drawing in Rome presents the full breadth of the composition, which seems to be the case, then it was flanked by a standing figure at each side and had a playful child in each corner. The center was occupied by three figures, a seated woman nude from the waist up, a standing man before her with his back toward us, and behind the woman, a man leaning forward, also nude from the waist up, as he is in the painting, clutching a bundle of drapery. It seems also that the outward diagonal gesture of the foremost man continued the similar recommending gesture of the Virgin at the top of the picture.

This remarkably mobile arrangement of plastic forms in space, including the way they relate the top of the picture to the bottom, recalls Raphael’s Transfiguration, the subject of which is similar to that of Rosso’s picture. But if Raphael’s painting was recalled by Rosso it was only in the most general terms as no specific motifs suggest any greater dependence. What Rosso’s design more clearly indicates is the study of Pontormo’s recent paintings and a more profound concern with them than is suggested by the merely Pontormesque incidents in the Sansepolcro Pietà. The heads of the two women in the Rome drawing are very much like the two immediately to the left of the Virgin’s head in Pontormo’s Entombment in S. Felicita, and the smooth and full forms of Rosso’s figures resemble Pontormo’s. But in addition to these specific similarities there is also the compositional relation of Rosso’s central figures that is Pontormesque. As in Pontormo’s Entombment Rosso’s figures turn obliquely into the space of the picture and in a revolving contrapuntal manner in respect to each other. No one figure fixes the center of the composition of the lower half of Rosso’s early conception for his picture as none does in Pontormo’s altarpiece. The figure with his back to us may have been inspired by the woman turning toward the Virgin in Pontormo’s Entombment, although the swing of his body and limbs looks even more like that of the foremost figure in Pontormo’s Legend of the Ten Thousand Martyrs in the Pitti [Fig.Pontormo,Legend]. If this association between Rosso’s drawings and Pontormo’s small picture in the Pitti is true then the latter would have to have been designed by mid-1528. The painting itself is generally dated a year or two and even three years later on the basis partly of Vasari’s testimony, although it has also been dated around 1528–1529.22 What, however, is also likely, rather than any specific dependence of Rosso’s design upon Pontormo’s Legend of the Ten Thousand Martyrs, is Rosso’s independent renewed exploration of Michelangelo’s art stimulated by Pontormo’s Michelangelism in his Entombment. Rosso’s figure turning into the composition is actually a more evolved version of a similar Michelangelesque figure that appears, clothed, in his early Assumption, and as Adam in his Roman Temptation of Adam and Eve of 1524. But there is no earlier figure that is so rhythmically complex and supple as the one in the foreground of the drawing in Rome. While Rosso seems to have studied Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel figures, or drawings from them, as suggested by the poses of the two outer saints in the Louvre copy of a lost drawing for the Christ in Glory, it is very probable that he also gave serious attention once again to the Battle of Cascina, or to a copy of it. The poses of the three central figures of the lower half of the early projected Christ in Glory suggest individually, and in relation to each other, those of several figures in that grand composition by Michelangelo. The static density of the Sansepolcro Pietà has been replaced by an openness in the relationship of forms, as already appeared in Rosso’s design for Lappoli’s Adoration, and by the most knowing, flexible, and controlled movement of the human body thus far visible in Rosso’s art. This kind of Michelangelesque movement and grand corporealness was to a large extent abandoned when the Christ in Glory was re-designed and executed a year later. But Rosso’s concern with these qualities was not immediately given up as can be seen in his next few works.

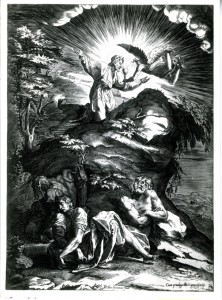

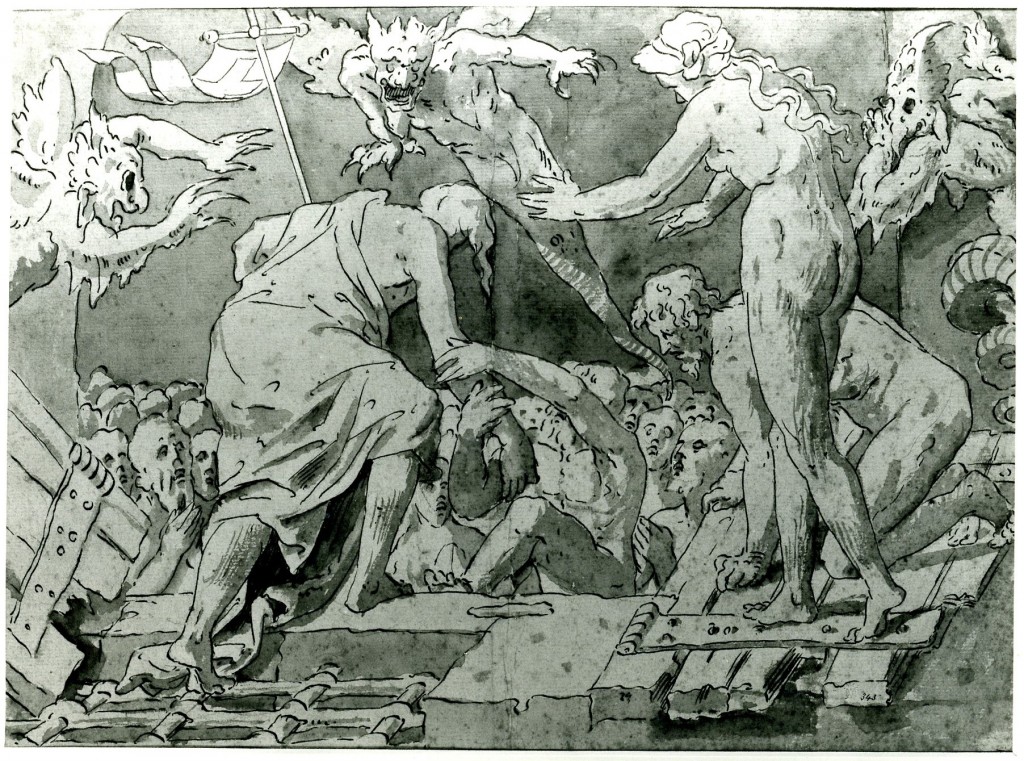

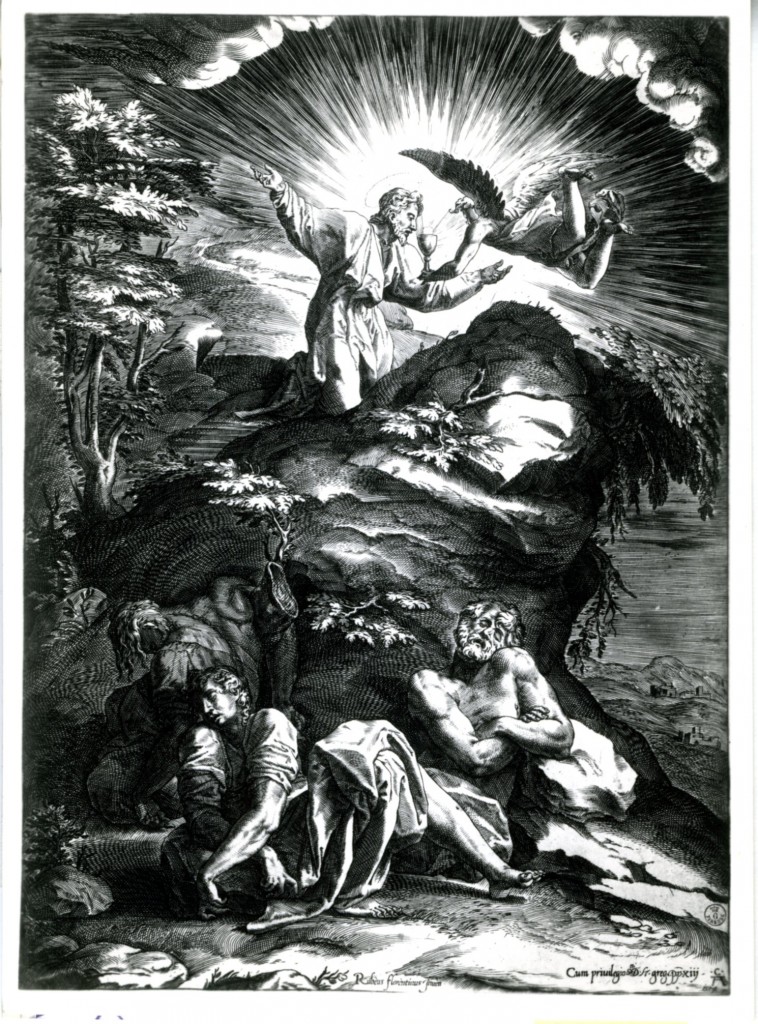

BORGO SAN SEPOLCRO & PIEVE SANTO STEFANO

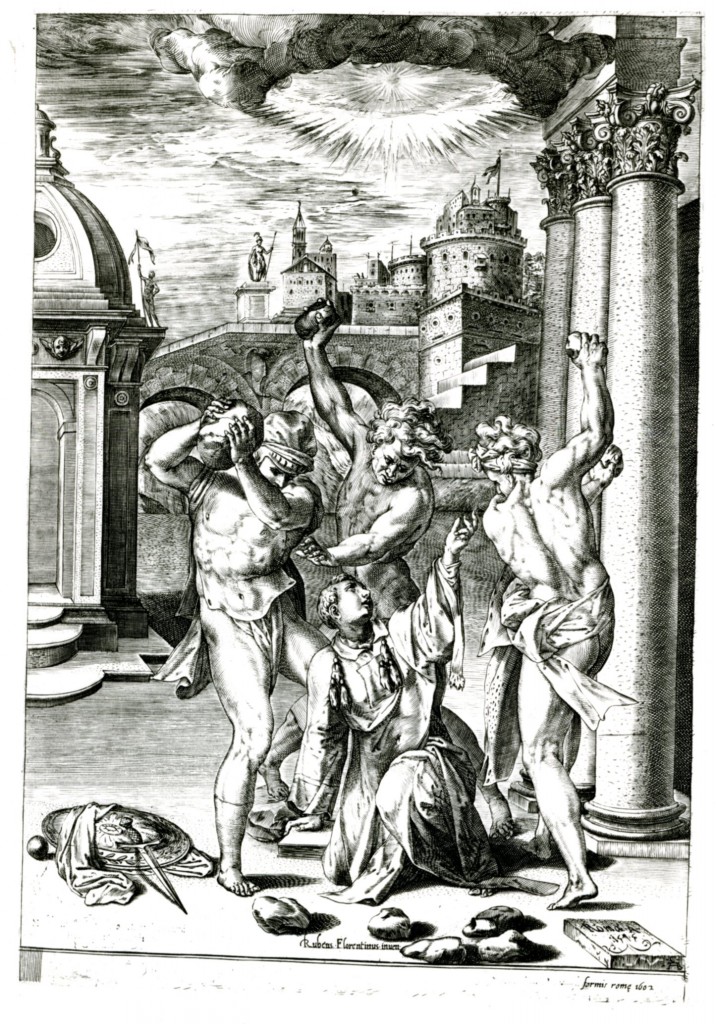

The accident—the collapse of a roof, according to Vasari—that destroyed the first panel for Rosso’s altarpiece was, it seems, followed by “un mal di febbre sì bestiale, che [Rosso] ne fu quasi per morire,” whereupon he left Città di Castello for Borgo Sansepolcro. Vasari came to visit him there, accompanied by Cristofano Gherardi to whom Rosso gave some of his beautiful drawings that the sixteen year old artist carefully studied.23 “Seguitando quel male con la quartana, [Rosso] si transferì poi alla Pieve a Santo Stefano a pigliare aria;…” This would probably have taken place late in the summer or in the early autumn of 1528. No work is known to have been done at this particular time but it is possible that the Stoning of Saint Stephen engraved in reverse by Cherubino Alberti in 1575 and inscribed with Rosso’s name [CENTER LARGE Fig, E.2] was designed while Rosso was recuperating only a short distance from Borgo Sansepolcro at Pieve di S. Stefano. As elsewhere at other times he created drawings in gratitude for the help he received although in this instance no artist is mentioned who might have done a painting from Rosso’s drawing. The setting, showing early Christian Rome with the Castel Sant’Angelo and Old Saint Peter’s and foreground details of imperial Rome, were added by Alberti to accompany this first century martyr whose execution, however, took place in Jerusalem (Acts 6:5–15 and Acts 7:55–60).

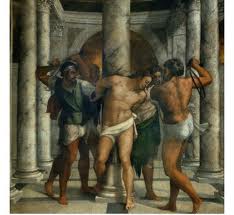

The composition of the figures in this scene bears the closest resemblance to the central part of the lower half of the early project of the Christ in Glory for the Città di Castello. [CENTER FULL SIZE Fig. E.2c NEW CROPPED SCENE OF FIGURES ONLY (ALSO ADDED TO THE CATALOGUE ENTRY) & here in text below it SMALLER Fig.D.29] As in the drawing in Rome for the Christ in Glory, the muscular and freely moving figures in the Stoning of Saint Stephen are Michelangelesque in their inspiration. The figures in the drawing recall to some extent those in Sebastiano del Piombo’s Flagellation in S. Pietro in Montorio [Fig. Sebastiano del Piombo, Flagellation,Rome]; a resemblance is even closer to the figures in the copy attributed to Giulio Clovio, at Windsor Castle, of Michelangelo’s lost drawing for this painting [Fig.Flagellation,Windsor Castle].24 Not only does the placement of Rosso’s figures define the space of this composition the postures and gestures of the figures also elaborate the drama of the event in a continuous spatial manner. The upraised arm, lowered shoulder, and downward glance of the executioner at the right is complemented by the supplicating pose of the saint set against the swinging pose of the forward facing stoner at the back. The line of his left arm is continued by the line of the left arm of the figure at the left, whose torso, right leg, and glance reciprocate those of the figure at the right. Each form in Rosso’s design has its precise spatial relationship to the other forms in the composition, and each posture and gesture finds its counterpart in some other posture or gesture. But the order of this picture is not that dense, almost suffocating, symmetry of the Sansepolcro Pietà, nor the rigid system of Sarto’s contemporary works mentioned above. Rosso’s order strikes one as that of an earlier moment in the history of Central Italian painting, recalling the order of Sebastiano’s Flagellation and Raphael’s Galatea [Fig.Raphael,Galatea], however without their spatial amplitude. Looking at Alberti’s print in conjunction with Rosso’s drawing in Rome for the Christ in Glory the precise description of Rosso’s figures—their anatomy, their wavy hair and their drapery—and the nature of their poses that suggest, though only slightly, a strain beyond what would be natural postures, differentiate Rosso’s figures from Sebastiano’s and Raphael’s. This may well be independent of the effect of Alberti’s translation of Rosso’s lost drawing. But Rosso’s figures are not so different from Michelangelo’s contemporary figures in the Medici Chapel. Even the correspondences of Rosso’s figures in the Stoning of Saint Stephen suggest the manner of the design of the Medici tombs.

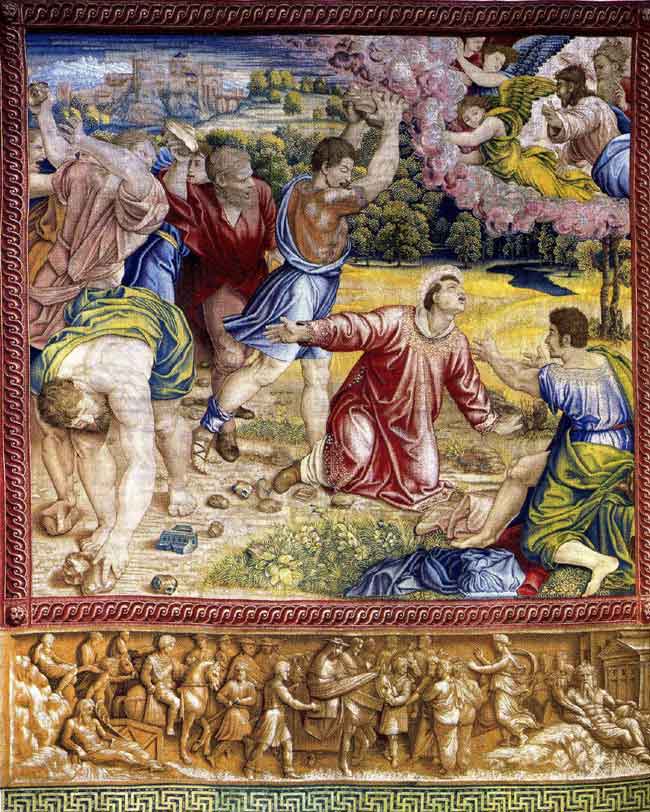

The correspondences of the figures in Rosso’s scene are, however, sufficiently emphasized to suggest something of the ritualistic quality of the Sansepolcro Pietà. In spite of the physical activity that is depicted, Rosso’s scene of Saint Stephen’s martyrdom does not possess the feeling of exalted, even heroic, passions of Raphael’s tapestry of the same subject [Fig.Raphael,Saint Stephen]. Nor is the characterization of Rosso’s saint of the kind of Giulio Romano’s in his altarpiece of the same subject in Genoa [Fig.Giulio Romano,Saint Stephen]. In Raphael’s and Giulio’s scenes the saint looks up toward Christ and God-the-Father. Neither appears in Rosso’s Stoning of Saint Stephen. Athough Alberti could have altered Rosso’s figural composition the print seems in all its details—note especially the wavy hair of two of the flagellators—a faithful reproduction of Rosso’s conception of that part of the scene. The fallen saint, who supports himself with his right hand upon a book, the Bible, looks up and gestures with his left hand (the right in Rosso’s lost drawing), seems to be directing his attention upward in the direction of his raised hand as though in supplication to something beyond the limits of the area between the two executioners at the right and beyond the limits of the scene of the killing. In the Acts of the Apostles (7: 60) it is written that at his stoning Saint Stephen “kneeled down, and cried with a loud voice, ‘Lord, lay not this sin to their charge.’ ” Rosso may show Saint Stephen praying for the deliverance of his persecutors.

AREZZO

After his stay at Pieve di Santo Stefano, Rosso moved to Arezzo “dove fu tenuto in casa da Benedetto Spadari,” the pupil of Guglielmo da Marcilla as reported by Vasari. He had settled in Arezzo certainly by 24 November 1528, the day that he received the commission to do a series of frescoes for the church of the Compagnia della S. Maria delle Lagrime, of which Benedetto Spadari was a member and a witness to the contract. This series included an Allegory of the Immaculate Conception, which will be discussed later. The same subject was represented somewhat differently twice again by Rosso in the couple of years before he left for France. It is likely that one of them known from a drawing in the Galerie Hans in Hamburg (D.30) was created at just about the time as the first design for the Christ in Glory and the Stoning of Saint Stephen, or, more likely, only slightly later at the beginning of his work on the Lagrime frescoes in Arezzo.

PLACE CENTER LARGE [Fig.D.30]

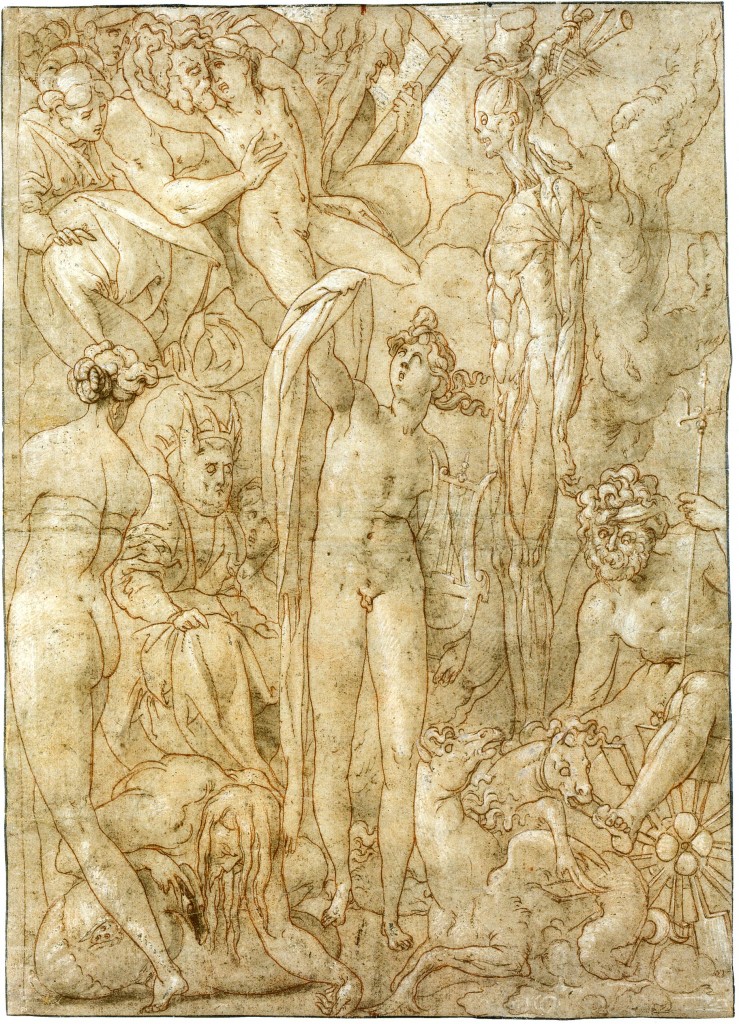

The allegory of Franciscan origin, newly elaborated out of sources that have a long tradition, shows God-the-Father touching the Virgin with a scepter as Ahasuerus had touched Esther saying: “This law was made for all human beings but not for you.” The Virgin stands with her foot on the head of Satan, as prescribed in Genesis. At her sides are David with his harp and Moses with the Tablets of the Law. Below Adam and Eve stand before the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, Eve holding a piece of fruit in her right hand while she gestures toward the tree as Adam reacts to what she is saying to him. They are flanked by three bishops, two the Latin Fathers, Saint Ambrose and Saint Augustine, the third, one of the Doctors of the Church, Saint Anselm, and by the largely nude Saint Jerome, another Latin Father, as a penitent.25 The design of this altarpiece could have been intended for the church of San Francesco in Arezzo, either as a commission Rosso sought or possibly to be executed by another artist, perhaps an alternative to Lappoli’s Adoration of the Magi.

The composition is related to the symmetrical positioning of the figures in the Adoration of the Magi that Rosso made for Lappoli’s altarpiece for the high altar of S. Francesco in Arezzo, which similarly has its figures clearly presented in shallow space across the height and breadth of the composition. At the same time the Allegory also appears related to his early design for the Christ in Glory. The two seated figures of David and Moses with their Michelangelesque postures are quite like the seated female saints represented in the Louvre drawing related to the upper part of the the Città di Castello picture. It is probable that the relation of these women to Christ, who is not copied in the Louvre drawing, was originally more or less as it is in the finished altarpiece and this arrangement is similar to that of the standing Virgin and the seated figures flanking her in the Hamburg drawing. But in spite of its grand formality, the symmetry of Rosso’s Immaculate Conception is remarkably flexible, and again in a Michelangelesque manner, suggesting the figures of the Medici tombs. The sideward slung figure of God-the-Father, adapted from Rosso’s Creation of Eve in S. Maria delle Pace but made much more supple in its pose, balances the postures of Adam and Saint Jerome which are inclined in the other direction; God-the-Father’s outstretched left arm matches Eve’s. In the center of the drawing the relatively informal and spatially complex relationships of Adam and Eve resemble those of the central figures in the lower half of the design for the Christ in Glory. Both of these compositions appear, even as one must know them in fragmentary and not altogether autograph terms, to be concerned with very similar artistic issues that introduce into Rosso’s art not simply a new kind of heroic order but also at this particular time a new kind of Michelangelesque involvement of forms that stems from what, it seems, Rosso had recently seen in Florence.

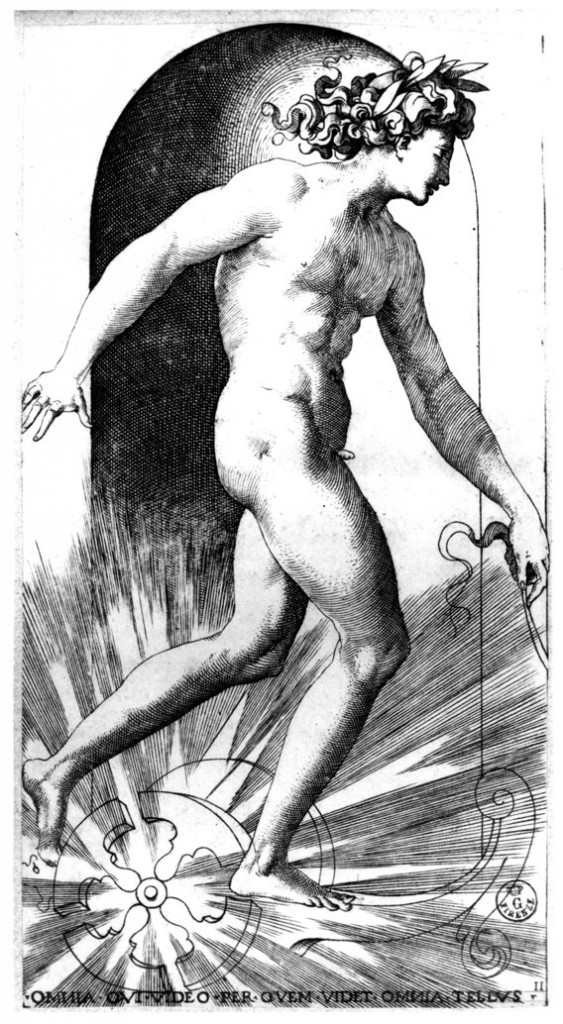

The basic theme of the Allegory is the same as that of one of the compositions for a half-lunette fresco that Rosso planned for the church of S. Maria delle Lagrime, and as they also share certain stylistic features it is very probable that they were both invented about the same time. The subject of these compositions and those of the other Lagrime designs will occupy us later, but it has to be recognized from the start that, traditional as their iconographical sources are, they are also unusually treated, revealing new modes of expression in Rosso’s art. The S. Maria delle Lagrime Allegory of the Immaculate Conception, known from a copy of a lost drawing in the Louvre (D.31) and from an original drawing in the Uffizi (D.32), is simpler in its iconographical program than the Hamburg drawing, in part, no doubt, because it was planned as part of a series of frescoes rather than as an altarpiece. But it is also more unusual in showing the pagan Apollo and Diana as allegorical attributes of the Virgin dressed in the Sun and the Moon. There is also a grand expansiveness to this composition that distinguishes it from the more compact designs of the other Allegory of the Immaculate Conception and the earlier Christ in Glory and that makes the fresco design one of the most profoundly Michelangelesque invention of Rosso’s career.

The only earlier work by Rosso comparable to the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception that he designed for the S. Maria delle Lagrime is the pair of frescoes above the entrance to the Cesi Chapel in Rome. Here, too, the picture areas are each a half lunette, and the subjects of these frescoes also deal with the nude figures of Adam and Eve. It is clear from the poses and gestures of the Michelangelesque nudes in the Immaculate Conception drawings that Rosso brought his Roman frescoes to mind here. Given the subject of the later composition and the shape of the area to be frescoed in Arezzo this recollection, one might have to assume, was inevitable. But no other Roman design by Rosso appears reflected in this allegorical composition nor does any other later Roman work by him suggest the modifications of Rosso’s Michelangelesque manner of the Cesi Chapel frescoes that might significantly account for the different Michelangelesque manner of the Aretine work. The huge, lumbering bodies of the Roman frescoes, that were so ambitiously derived from the nudes of the Sistine Ceiling, have been reconsidered in the light of Michelangelo’s later Florentine figures, and with a concern with Michelangelo’s conceptions that is more fully and deeply understood by Rosso. In the earlier drawing in the Louvre knowledge of Michelangelo’s conception for his Night is evident. Anatomically Rosso’s figures in his allegory, as seen especially in the later of the two drawings in the Uffizi are more finely described than those of the Cesi Chapel and recall more precisely his Florentine figures. But the anatomy of the later figures done in Arezzo appears now more functional and at the same time more imaginatively explored. The Eve of the second drawing moves expansively beyond the compactness of the earlier Michelangelesque figure. The poses and gestures of his figures express states of being and feelings that are complex but at the same time are not idiosyncratic or bizzare as are many of his earlier figures. They are emotionally moving in a grand manner as they slowly turn, fall, rise and float in the narrow space around the straight-standing Virgin. The figures of Adam and Eve convey something of the same feeling of drifting loss as do the figures in Pontormo’s Entombment. There is also in Rosso’s scene an accomodation of the figures to the half-lunette shape in which they are placed that is both eloquent and graceful, evoking a quality of meaning that is beyond mere representation. In spite of its thematic dogma, the allegorical aspects of Rosso’s composition are carried stylistically by forms that are not rigid. They are rich and complex, but in a manner appropriate to the nature and value of the religious idea they illustrate without, however, over defining them.

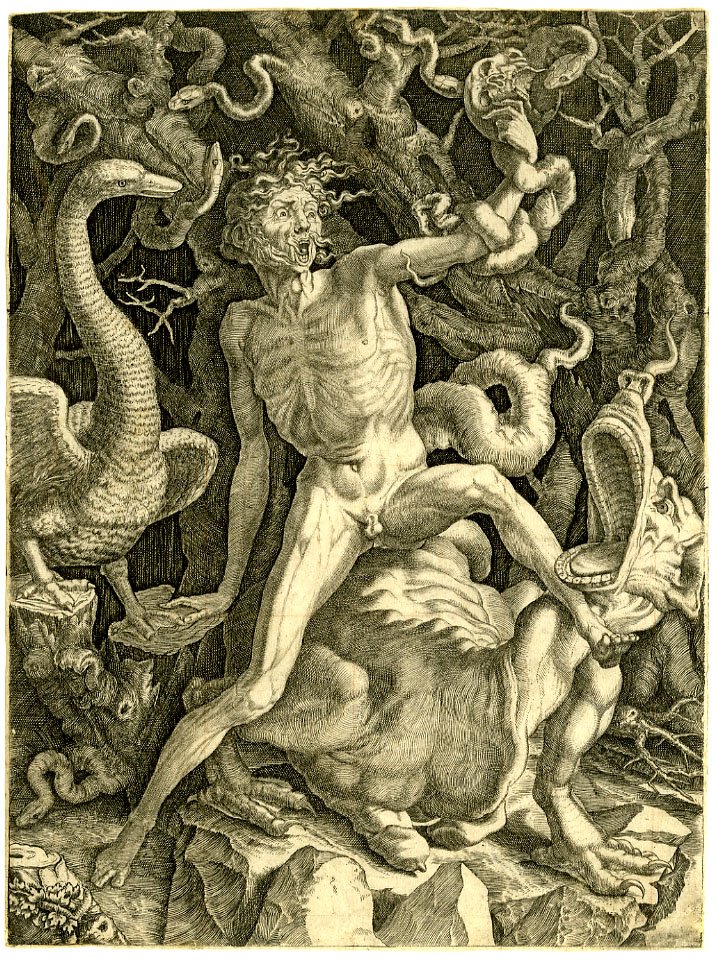

Vasari declared that the iconography of this Allegory of the Immaculate Conception was devised by the “bello ingegno di messer Giovanni Pollastra, canonico aretino ed amico del Rosso,” along with that of the other frescoes planned for S. Maria delle Lagrime. In spite of some of the unusual subjects of Rosso’s earlier works none of them, with the exception of the Christ in Glory before Rosso settled in Arezzo and the similar Allegory drawing in Hamburg that is elaborated with the figures of God-the-Father, David, Moses, three Fathers of the Church, and Saint Anselm, is iconographically so oblique as the scenes planned for S. Maria della Lagrime. This is not simply a case of Rosso’s very individual depiction of the subjects given to him, or of the receipt or use by him of a very special aspect of his subjects. Bizarre as the early Florentine Disputation (Fig.D.1b) appears to be, its references are directly to death and what is represented is a straightforward discussion. The personification of Fury (Fig.E.18a) surrounded by symbolic animals and other details in the Roman print of 1524 is also, both intellectually and visually, immediate in its horrifying effect. In Rosso’s Sposalizio and in the Visitation and Adoration of the Magi that he designed for Lappoli, the principle subjects of the pictures are contemplated or acknowledged by particular figures in the foreground that do not belong to the narratives. Such witnesses, suggesting the context of the sacra conversazione, are not new here to Italian art. There is, however, a demonstrativeness about these figures in the pictures that Rosso designed for Lappoli, beyond what appears in the Sposalizio, that makes a point of the subjects of these pictures as having some special theological meaning. Nevertheless, the narratives themselves are easily understood. In Rosso’s Moses and Eliezer the narrative subjects of the pictures appear transformed into grand emblematic statements without, however, overtly employing symbolic material.

The Christ in Glory, commissioned on 1 July 1528 and first designed immediately thereafter, is the earliest work by Rosso the iconography of which has the aspect of a fabrication that mystifies. Rosso was commissioned to paint not a narrative subject but the figure of Christ “resuscitato a glorioso” with the Virgin, Saint Anne, the Magdalen, and Saint Mary the Egyptian, with, below, “più e diverse figure the denotino e representino el populo,” and “con quelli Angelic che a lui [Rosso] parerà de accomodarre.” In the finished picture, and most probably in the first version of it as well, the Virgin to Christ’s right recommends the “populo” to him who looks at the figures below with both his arms raised. The difficulty or remoteness of this large image lies in the reticence of the Virgin’s gesture that retards our recognition of the dramatic possibilities of the subjects of this picture, and in the hieratic appearance of the picture, as known from the finished altarpiece at least, that one senses holds meaning in symbolic terms beyond the picture’s implied narrative suggestions. The figure of Christ above his people can be seen as the symbol of life after death as well as the benevolent Pantocrator. We do not know if Rosso took any role in the original formulation of the iconography of this picture but he did not included any angels that the contract allowed. It was, in any case, the first time that he had to give pictorial form to such a largely symbolic scheme as this and left to choose the members of the populo.

We also do not know if Rosso had any part in the only slightly later iconographical scheme of the frescoes planned for the new atrium of S. Maria dells Lagrime in Arezzo (also dedicated to the SS. Annunziata), the program of which was devised by the humanist Giovanni Pollastra, according to Vasari as noted above. The document of 24 November 1528 commissioning this work called for the painting of the “voltam … super altare prefate Marie Virginis gloriose” with “tres mezi tondi con tre finestre in dicti mezi tondi, et cum imaginibus Beate Marie semper et eius istoriis.” What the subjects of the pictures were to be is not dictated in this document. The commission to fresco the vault and upper wails of the atrium, the construction of which had been completed in 1523, first went to Niccolo Soggi on 24 May 1527 with subjects that were to be supplied by the syndics of the Compagnia della Madonna delle Lagrime. After the completion of one scene Soggi’s work was to be judged and the remainder of the project granted or denied to him on the basis of this judgment. Soggi’s Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl [Center above each other Fig.Soggi,Arezzo & Soggi,Arezzo,Lunette] was deemed unsatisfactory on 22 March 1528 and the remainder of the project was taken from him. About this time, after 1 March but before 24 April, Rosso was briefly in Arezzo, where he designed a Resurrection for Vasari. It is possible, as suggested much later by Vasari, that Rosso’s presence in Arezzo may have been partly responsible for Soggi losing the commission recalling Rosso’s commission of the Borgo Sanseplocro Pietà that was given up by Raffaello da Colle. The commission to Rosso in November of 1528 was for the same wall areas that Soggi would have painted. Vasari said that Rosso was to complete the project begun by Soggi which would seem to indicate that his fresco was not to be destroyed. It is therefore possible that the iconographical program for Rosso’s frescoes had already been devised by Pollastra for Soggi’s project. What, however, we can be sure of is that Rosso’s handling of the thematic material supplied by Pollastra would give to it meanings quite different from what Soggi could have invented for it, as evident in the stiff, matter-of-fact, and uninspired depiction of his Augustus and the Sibyl.26

Although Rosso made a model of the entire project (L.23) Vasari said he completed only four cartoons “in una stanza che gli avevano consegnata in un luogo detto Murello“. He described, however, only three, and visual evidence for three survives for the areas of “mezi tondi”. “In uno fece i primi parenti legati allo albero del peccato, a la Nostra Donna the cava il peccato, di bocca, figurato per quel pomo, e sotto i piedi il serpente, e nell’aria (volendo figurare ch’era vestita del sole a della luna) fece Febo a Diana ignudi.” This is the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception known from a partially unfinished original drawing in the Uffizi (D.32) and a copy of another slightly earlier drawing in the Louvre (D.31) [PLACE ABOVE EACH OTHER, LARGE, CENTER: Fig.D.31 & Fig.D.32].

“Nell’altra, quando l’Arca foederis è portata da Mosè, figurata per la Nostra Donna da cinque Virtù circondata.” The five virtues mentioned in this description may make it possible to identify this composition with a drawing clearly copying Rosso’s drawing style in the British Museum [CENTER Fig.D.33A], provided one interprets the drawing as showing the stairway leading to the Ark of the Covenant rather than the ark itself. “In un altro è il trono di Salamone, pure figurato per la medesima, a cui si porgono voti, per significaro quei che ricorrono a lei per grazie.” Rosso’s drawing in Bayonne [CENTER Fig.D.34] is specifically related to this description. Vasari also said that in addition to “un bellissimo modello di tutta l’opera” (see above) Rosso made “uno studio d’ignudi per quell’opera, che è cosa rarissima (L.25).” But “andò temporeggiando in fare i cartoni per farla finire a Raffaello dal Borgo ed altri, tanto ch’ella non si fece.” Rosso’s model is lost as well as his “studio d’ignudi,” but his project can be partially known from the drawings that survive. Raffaello dal Borgo was the same artist who gave up his commission so that Rosso could paint the Borgo San Selpolcro Pietà.

Vasari’s descriptions of the three scenes suggest that he knew the nature of their subjects not only from Rosso’s drawings and cartoons but also from verbal or written account of them. For none of the three scenes, although theologically canonical, is of a common subject, and the one subject that is less unusual, the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception, is depicted in an unprecedented manner. The subject of the Throne of Solomon would not have been immediately recognizable by many. And the allegory of the Virgin in terms of the Ark of the Covenant, as detailed by Vasari and visualized by Rosso, is even more recondite at this time. Lettering on the plaques and the banderole in it would have clarified its meaning. In the context of these scenes Soggi’s fresco looks simple indeed, although its subject is also not a common one.

[CENTERED: PHOTOGRAPH(S) OF ATRIUM]