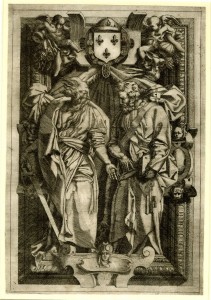

Etching by Master I.♀.V., 34.1 x 23 L (London, 1850-5-27-69). Inscribed, in dry point?, at bottom center: IR / INVEN / TEVR / IVB (barely visible and done over a half-circle decorative motif that has not been entirely scraped away to provide an irregularly shaped area for the inscription).

Fig.E.98a (London, 1850-5-27-69)

Fig.E.98b (London, 1850-5-27-69, detail, inscription)

Bartsch, XVI, 1818, 389-390, no. 33, as Anonymous, School of Fontainebleau, after Rosso. Herbet, IV, 1900, 353 (1969, 203), 17, as Master I.♀.V., after Rosso. Herbet stated that the letters IR refer to Rosso, and IVB to the etcher. Zerner, IB, 33, 1979, 310.

COLLECTIONS: London, 1850-5-27-69; W.3-145 (Prints after Rosso, fragmentary). Paris, Ba 12. Vienna, Vol. It.III.4, p.69.

LITERATURE:

Mariette, Abécédario, V, 1858-1859, 18, as anonymous after Rosso.

Kusenberg, 1931, 166, as Jean Vaquet, after Rosso.

Zerner, in EdF, 1972, 297, no. 367, with Fig. (Paris), as Master I.♀.V., after Rosso.

Colin Eisler, “Engraved Confrontation: Duvet’s ‘Moses and Peter,’” The Print Collector’s Newsletter, X, 5, 1979, 146, as after Rosso and influential on Duvet’s print.

Borea, 1980, 263, under no. 678, as Monogramist I+V, or IVB, or IVR, as after Rosso.

Carroll, 1987, 191, n. 1, under no. 62, as by Master I.♀.V.

Béguin, 1990, and Fig. 98 (Paris), as done before the engraving attributed to Boyvin.

Miller, 1992, 113, n. 9, seemed to accept Beguin’s arguments.

Béguin, 1994, 271, 277, n. 59, the figures stylistically related to those in a drawing related to the decoration of the North Cabinet of the Gallery of Francis I, and as made for Cardinal Jean de Lorraine.

This etching, in the same direction as the engraving attributed to Boyvin (Fig.E.8a), could be a copy of that print or it could have been made from the same lost model. Certain details, such as the possibly more subtle relationships of the lights and darks throughout, suggest that the etching was not made from the engraving. This may also be indicated by the fact that the etching is not in reverse of the engraving. The etching shows some slightly different details aside from the inscription on the engraving, which may not have been on a common model. At the top, a shield bearing the fleur-de-lis, surmounted by a crown, and surrounded by a ribbon decorated with scallop shells and carrying a small medallion showing St. Michael replaces the (uninscribed) Tablets of the Law in the engraving. At the bottom, a small patch bearing the faintly etched inscription given above replaces one small half-circle decorative motif in the engraving, leaving traces of it still visible. Iconographically, but also in their plasticity and placement, the tablets of the law seem more appropriate to the composition as a whole than the French royal emblem in the etching. In spite of Beguin’s argument to the contrary, the importance she recognized in the Tablets of the Law in the engraving gives that print a significance lost in the etching. Furthermore, the placement of the tablets in the print has a precision that is not found in the arrangement of the variety of details in the etching.

According to one dated etching, Master I.♀.V., named from his monogram, which, however, does not appear on this print, was active as early as 1543 (see Zerner, in EdF, 1972, 293).1 It is, therefore, possible that this etching was done before the engraving, which was, however, made independently of the etching. Zerner believed the design may have been for a relief rather than a painting.

Eisler’s suggestion that the two figures are freely based on the central ones in Raphael’s School of Athens does not seem especially cogent inasmuch as other models, such as the bronze reliefs by Donatello on the doors in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, appear more closely related (see D.2 for evidence that Rosso knew these doors).

1 Boorsch, in French Renaissance, 1994, 82-84, suggested that Master I.♀.V. may possibly be identified with Jean Viset, who was a “printmaker [graveur] and cutter of stories in copper [tailleur d’hystoires en cuivre]” living at Fontainebleau already in May 1536. If this identification is correct, then, according to Boorsch, he would be the earliest of the Fontainebleau etchers, which would account for “the unevenness of his style and the experimental, one might say self-taught, quality of his work.” Boorsch thinks that the Venus and Minerva [E.138] may be by the same etcher; she also recognized him as the etcher of the Birth of Venus [E.148]. Acton thought the Twins of Catania [E.142] probably also belongs to Master I.♀.V. It may, however, be necessary to consider why an etcher would be called a “cutter,” a term that seems more appropriate to an engraver.