1539 or 1540

London, British Museum, no. Pp. 5-132.

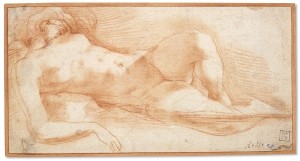

Red chalk, over traces of black chalk lines on and near the right thigh, 12.6 x 24.4; laid down; wm.? There is a hole in the lower left corner, the lower right corner is missing, and the drawing is slightly soiled, especially at the left. Inscribed in ink at the lower right: Rosso.1

PROVENANCE: Sir Joshua Reynolds (Lugt 2364); at the right of the inscription there may be another collector’s mark in ink, possibly reading l.s, and not in Lugt. R. Payne Knight Bequest to the British Museum, 1824.

LITERATURE:

W. H. Carpenter, Manuscript catalogue of the Richard Payne Knight Collection, Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum, 1845, as Rosso.

Berenson, 1903, no. 2444, as Rosso.

Kusenberg, 1931, 136, 142, no. 51, as doubtful as Rosso.

Berenson, 1938, no. 2444, as Rosso.

Barocchi, 1950, 226-227, n. 3, mentioned but not discussed.

Berenson, 1961, no. 2444, as Rosso.

Carroll, 1964 (1976), I, Bk. I, 254, 256-259, II, Bk. II, 423-427, D.51, III, Fig. 130.

Carroll, 1966, 176-180, Fig. 9, as Rosso and as probably datable after 1536-1538, and as possibly related to the sleeping woman in the Loss of Perpetual Youth in the Gallery of Francis I, but in her pose like the figure of St. John in the Los Angeles picture.

Béguin, 1970, 9, 82, Pl. IX, as Rosso, from his French period.

Béguin, in EdF, 1972, 182, Fig., 185, no. 207, and in Fontainebleau, 1973, I, 42, Fig. 247, II, 64, no. 207, as Rosso, from his French period.

Béguin and Pressouyre, 1972, 128, as Rosso.

Carroll, 1973, 74, Fig. Raggio, 1974, 74, as Rosso, and perhaps for the Gallery of Francis I.

Carroll, 1975, 25, 27, Fig. 14, 28, as Rosso, and a late drawing.

Carroll, 1978, 25, 30, Fig. 10, 36, as Rosso, around 1538-1540.

Lévêque, 1984, 150, Fig.

Turner, 1986, 154, no. 111 and Color Pl., as Rosso, in France.

Carroll, 1987, 368 and Fig., 369, as Rosso in 1539 or 1540.

Béguin, in Delay, 1987, 76, 208, 211, Color Pl., as recalling the figures of Michelangelo’s Medici Tombs and of his Leda.

Béguin, 1992 (1987), 89, as a free study for the reclining woman in the Lost Youth fresco in the Gallery of Francis I.

The posture of this reclining and slumbering nude woman is reminiscent of that of the sleeping nude in Rosso’s Loss of Perpetual Youth in the Gallery of Francis I (Fig.P.22, II S d) and of that of the young St. John the Baptist asleep in the lower left corner of Rosso’s picture in Los Angeles (Fig.P.24a). In its Michelangelesque aspects, recalling the figures in the Medici Chapel, the Reclining Nude Woman is also similar to the nudes that frame the Death of Adonis in the gallery (Fig.P.22, III S c). In her proportions she is especially similar to the nude in the lower left corner of this wall, a figure whose pose is inspired by Michelangelo’s Leda. While the pose of the Reclining Nude Woman is not like that of the Leda, the erotic implications of the British Museum drawing may well be dependent on Michelangelo’s image. Given these associations, the drawing is wholly understandable as an invention by Rosso, not only because it is closely related to other figures certainly by him but also because it shows an interpretation of Michelangelo’s figures similar to that found elsewhere in Rosso’s art.

The handling of the light in the drawing is very characteristic of Rosso. It boldly rakes across the figure quite as it does in Rosso’s study for the figure of St. Sebastian (Fig.D.7) in the Dei Altarpiece, in the Louvre Pietà (Fig.P.23a), and in the painting in Los Angeles. Some of the shadows on the figures in all of these works, instead of casting the figures into relief, emphasize, by contrast, certain passages of light that bring attention to the surface of the figures. Also, in all of these works, the light creates diagonally cast shadows across the bodies of figures.

Although more loosely executed than the study for St. Sebastian, the Madonna della Misericordia (Fig.D.35a), and the Martyrdom of Sts. Marcus and Marcellinus (Fig.D.70a), the Reclining Nude Woman does resemble them in the almost total suppression of line in favor of light and shade. Line is used only where it is absolutely necessary to prevent the total dissolution of the limits of what is represented. The looseness of certain parts of the drawing has a certain correspondence in Rosso’s Pandora and Her Box (Fig.D.67a), but it is even more similar to what appears in his Design for a Tomb (Fig.D.81a). It is true that both of these drawings are executed in pen and ink and wash, but they do suggest, especially the latter, an extension of Rosso’s generally tight draughtsmanship in these media into a freer handling of them that appears also to be represented, but in red chalk, in the Reclining Nude Woman. As it is not possible to dissociate the draughtsmanship of that drawing from the conception that it presents – in a way that would suggest a copy – it is reasonable to conclude that the drawing is an autograph work by Rosso.

As the Reclining Nude Woman is most closely related to figures in works that Rosso created in France – and not especially to the overtly Michelangelesque figures that he did in Rome – it is most likely that it was executed after 1530. Although similar to the nude woman in the Loss of Perpetual Youth, the Reclining Nude Woman is more similar to the later figures framing the Death of Adonis in the Gallery of Francis I and to the male nudes flanking the Education of Achilles (Fig.P.22, II N a). These figures would seem not to have been done before the latter part of 1536. The Reclining Nude Woman is also similar to the Seated Male Nude in the British Museum (Fig.D.68a), probably done around 1536. But there is a degree of compositional enclosure and self-containment about these figures that is not found in the more open and sprawling Reclining Nude Woman. In these respects, she is more like the fainting woman at the bottom of the Martyrdom of Sts. Marcus and Marcellinus, a drawing that may have been done around 1537, as suggested by its apparent compositional and dramatic extensions of what is found in the Scene of Sacrifice that was designed for the gallery late in 1536 (Fig.P.22, VII N a). But the British Museum figure is not only more freely drawn than the woman in the Martyrdom drawing, it is also grander in its conception. That grandness and the ease with which it is accomplished suggest that the Reclining Nude Woman may be an even later drawing, done about the time of the Design for a Tomb and the painting in Los Angeles. That painting may very well date from the last year of Rosso’s life and the drawing at the same time, or perhaps in 1538. Grouped with these works, the Reclining Nude Woman would date from 1539 or 1540 and is probably approximately contemporary with Rosso’s Holy Family with St. Anne known from the good copy in Milan (Fig.D.82).