Early 1527

Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, no. 1979.67.

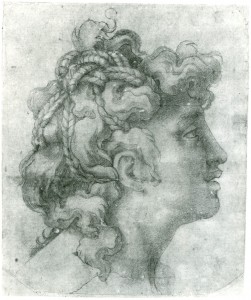

Black chalk, squared with a stylus, 17.9 x 14.1, the lower corners and upper right corner cut and filled, a tear at the bottom center, several holes and worn spots, lightly stained, and a horizontal streak of white pigment in the center across the left half of the drawing through the lower part of the ear; laid down; wm.? According to the museum’s file, inscribed on the verso (of mount?) in pencil: Pisa styl DOS 7 69A 1635 “Beau bri sans colori w.e. / beau bris sans col”. Some lines in the hair, and around the iris and the lips, may have been gone over.

PROVENANCE: Philip Hofer; Frances L. Hofer; bequeathed to the museum in 1979.

LITERATURE:

Michael Miller, in Master Drawings and Watercolors. The Hofer Collection, ed. Konrad Oberhuber and William W. Robinson, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Mass., 1984, 18, no. 4, 78, Fig. 4, as 17.8 x 14.1, and as attributed to Rosso by Konrad Oberhuber, and perhaps an early study for the head of the Virgin in the Christ in Glory.

Carroll, 1987, 23, 138-139, no. 46, with Fig., as Rosso, 1527, and as possibly a study for the head of Salome or Herodias in Rosso’s lost Beheading of St. John the Baptist.

Franklin, 1988, 325, 328, Fig. 88, as a “teste divina,” as difficult to imagine as Salome in Rosso’s lost Beheading of St. John the Baptist, and as similar to the head of St. John the Evangelist in Rosso’s Sansepolcro Deposition of 1527-1528.

Costamagna, 1991, 54, Fig. 8, 60, n. 18, as Rosso.

Gilbert, 1992, 217, Fig. 3, as Rosso, and related to Michelangelo’s teste divine.

Miller, 1992, 112, questioned the dating of the drawing in the Roman years to the exclusion of the period in Arezzo, although he found its relation to Caraglio’s prints significant.

Franklin, 1994, 146, Pl. 109, 155, 241, as Rosso, implying a Roman date, its relation to Rosso’s lost Beheading of St. John the Baptist not verified.

This profile head closely resembles the heads of the angels in the foreground at left and right in Rosso’s Dead Christ of 1525 or 1526 in Boston (Fig.P.18a; Fig.P.18c). The large locks of hair, the heavy-lidded eye with a rather pronounced and fleshy lower lid, the full lips, and the flat-topped ear are very similar to these details of the angel at the right. The head is also similar to Apollo’s in the Apollo in a Niche engraved after Rosso’s drawing by Caraglio in 1526 (Fig.E.36). The kind of coiffure of this figure appears in many works by Rosso including the Sposalizio of 1523 (Fig.P.13a), the slightly later Moses and Eliezer pictures (Fig.P.14e; Fig.P.15c), and the post Roman altarpieces in Borgo Sansepolcro (Fig.P.19c) and Città di Castello (Fig.P.20c). But the largeness of the locks, their broad waviness, and their being intertwined with braids are most similar to the same details of Proserpina’s hair in Rosso’s Pluto and Proserpina, designed by Rosso and engraved by Caraglio early in 1527 (Fig.E.46a).

The draughtsmanship of the drawing, especially the fine shading and the wavy lines outlining the patterns of the locks of the hair, is very much like that of Rosso’s study of 1524 (Fig.D.10) for the figure of Eve in the Cesi Chapel Fall of Adam and Eve. It is also like that of the St. Roch Distributing His Inheritance to the Poor of later the same year (Fig.D.13). However, there is a largeness about the forms of this profile head that is most like the profiles in the Pluto and Proserpina. The profile of the Fogg head is also similar to those of some of the women in profile in the first state of the Romans and Sabines print of early 1527 (Fig.E.48, Paris). Therefore, in spite of the fact that the drawing can be related to a variety of works of the mid-1520s, it is most similar to works done in Rome and to those done in 1527.

Although the drawing resembles Michelangelo’s teste divine drawings and Rosso’s own such later drawing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig.D.25a), without beads and ribbons or horns as in the New York drawing, the image in Cambridge does not look quite elaborate enough to be itself an independent testa divina. Furthermore, the open mouth and the slightly upward tilt of the head, which gives a decided direction to its glance, suggest that the drawing was made for a composition. The squaring of the drawing indicates this, too. It is just possible that the drawing was made for the head of Salome or Herodias in a Beheading of St. John the Baptist for which Rosso, according to Vasari, had made a “bozza” at the very end of his Roman period (see L.19). If this is true then it would mean that Rosso had actually begun work on, or at least made studies for, a large altarpiece, of which the lost oil sketch was a model. Work on the final painting might have been prevented, or stopped, because of the Sack of Rome.

Franklin questioned a relationship to Rosso’s lost “bozza” but did not take into account that the drawing is squared and that I thought the drawing not a study for a small bozza but for the large picture that I supposed would have been made from the oil sketch. The female profile does resemble the head of St. John in Rosso’s Sansepolcro altarpiece, but that painting was made only shortly after he had done the lost Beheading and the similarity of the heads need not mean an absolute chronological identity. I should again like to emphasize that the Fogg drawing is squared.

The drawing was kindly brought to my attention by Innis Shoemaker.