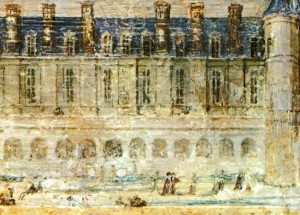

Château, Fontainebleau

c. 1531-1534

Fig.South façade center from P.22, I N

The documentation for the Gallery of Francis I and an account of Rosso’s possible participation in the design of its architecture are fully presented in P.22 and in Chapter VIII.

According to the specifications of 28 April 1528, over two years before Rosso arrived in France, the gallery was to be approximately 62.5 meters long, and six wide. There were to be casement windows in its long north and south sides. Two small cabinets, about four meters square, with windows, were to be built across from each other and projected from the middle of the long sides. At the ends of the gallery there were to be, at the east, a chapel, and at the west, another cabinet.

Before Primaticcio arrived in France early in 1532, Rosso began making plans for the decoration of the gallery. Two oval oil paintings on panel were executed for the gallery, indicating that before early 1532 a scheme had been devised for its paintings and stuccoes. While it is possible that the two oval pictures were intended for a shorter gallery set between the west cabinet and the chapel at the east, it seems more likely, given that these two end spaces are never mentioned again in the surviving documents after 1528, that by the time the oval pictures were executed the west cabinet and the chapel at the east had been eliminated.1 The elimination of the cabinet and chapel did not require major structural changes but it did lengthen the gallery and change the shape of its long walls. It is likely that the alteration of the original plan took place while Rosso was considering the decorations of the spaces that had been proposed before he arrived in France and I would suggest that the changes that were made to the architecture were the result of his decisions. While contemplating what decorations he would invent, it came to him to change the very space that he was to decorate.

Work on the decoration of the newly proportioned gallery had already begun in August 1533, possibly preparatory to the actual execution of the stuccoes and paintings in the gallery and in the north and south cabinets. The stuccoes themselves were begun in April 1534. At this very same time, on the south side facing the Cour de la Fontaine and the lake, construction was begun on a series of arches and vaults at ground level to contain six kitchens and six larders. But this masonry construction would also carry a terrace in front of and along the full length of the gallery at the level of its floor. According to Dan, this terrace was first built of wood and then replaced in stone in 1584.2 Very soon, the south cabinet was eliminated from the plan of the gallery and between April and November 1534 whatever, if any, had been built of it would have been destroyed to make way for a long terrace of equal breadth its entire length, which seems to have been largely completed by the end of 1535.

The decision to remove the south cabinet from the plan of the gallery may in the first instance have been due not only to the interest in having an exterior terrace, which could have gone around the south cabinet, but also in unifying the south façade of the gallery, facing the Cour de la Fontaine and the lake, as it appears in the small fresco under the Venus and Minerva in the gallery (Fig.P.22, I N h). The unification was further accomplished by a new design for the central recessed space flanked by narrow pilasters where the south cabinet with its window was or would have been. This arrangement continued the articulation of the façade, but because the central space, flanked by pilasters, was slightly narrower than the other recessed bays, the new space was closer to its adjacent windows than was the spacing between the broad piers elsewhere on the façade. Consequently, a more compact triad of bays gave a focus to the center of the façade that was reinforced by the peaked roof containing a dormer above it marking the center of the three matching dormers at the upper level of the gallery, as still visible in the small painted view in the gallery (Fig.P.22, I N h). In Du Cerceau’s print of 1579 (Fig.Du Cerceau Print, Gallery) the central triad has been regularized but still clearly focused by the peaked roof above containing a dormer.3

From Du Cerceau’s engraving of 1579, I assumed that this center bay showed a painted blind window. In the slightly abraded small frescoed view of the south façade, I thought I saw in the center of the south façade a slightly narrower painted window, that is as compared to the adjacent and better preserved flanking windows with which I thought it formed a triad. But recently, as stated under Summary in P.22, I noticed that in this smaller center area there appears not the painted description of a mullioned casement window but the painted image of a draped figure perhaps holding a scepter on a diagonal and seated under a light baldachin composed of tall, thin columns supporting a high dome (Fig.South façade center; Fig.P.22, I N j).4 This detail gives support to the suggestion that Rosso had a hand in the architectural shaping of the Gallery of Francis I by unifying the south façade with the elimination of the south cabinet and even further with the placement of a painted seated royal personnage, probably Francis I himself, occupying the exterior center bay and so relating now the south façade to what became a more centralized decoration within the gallery itself.

Guillaume proposed that the terrace running along the south façade, at first narrower where it went past the south cabinet5 and then, by the destruction of the south cabinet, the same width its entire length, joined another terrace running along the east front of the adjacent building. Facing the Cour de la Fontaine, this terrace led to the Pavillon des Poêles now fully under construction. There are no documents on the building of this terrace, even as many survive for the building of the gallery’s terrace, nor are there any views or plans of it. It is known only from the contract of 1558 for its destruction.6 Du Cerceau’s engravings were done two decades after its destruction and Rosso’s small painting of the Cour de la Fontaine stops just short of the west side of this space, although the very simple building at the east is fully depicted. Perhaps this west wing was still too incomplete and even its full design was not yet known. Only the Gallery of Francis I and the Porte Dorée were intended as the subjects of this “portrait” of the king’s most favored residence.

Guillaume’s interest was primarily functional in recognizing the solution to the problem of circulation at the château, that is, to get from the old building centered around the Cour Ovale to the new building under construction when the Gallery of Francis I that linked them was locked shut. With the south cabinet built as planned, this problem may already have been solved by the narrow space of the south terrace where it extended beyond the end of the south cabinet. This practical but uncomfortable and inelegant solution was majestically replaced by removing the south cabinet entirely and placing at the area it occupied a painted ceremonial image of the monarch seated under a baldachin at the center of Rosso’s now formally united south façade of the Gallery of Francis I.

As no documents or images of the west building are yet known, it is impossible to determine the appearance of this terrace or know its full purpose and the proposed extent of its use. A wooden terrace with a life-span for only as long as needed to complete the west building to which it was attached may have had little relationship with the original design and modifications of the Gallery of Francis I. For after the destruction of this second terrace the path from the Cour Ovale to the new château when the gallery was closed was its south terrace alone with its own exits into the buildings beyond the gallery at its west and the east ends, as seen in two of Du Cerceau’s prints of these sides of the Cour de la Fontaine (Fig.Gallery terrace, west exit and Fig.Gallery terrace, east exit).

On the interior, this wall, painted on the exterior with the image of the king, now gave a new central area to be decorated on the south side within the gallery. For this space Rosso planned his Nymph of Fontainebleau (Fig.E.103) in a horizontal oval frame, the only large fresco in the gallery with this shape, although it bore a relation to the upright oval oil paintings at the ends of the gallery. Instead of being cut into two halves by the entrances to two cabinets, the gallery now had a center of focus and a place, at and near the doorway of the North Cabinet, from which all the decorations in the gallery could be taken in. Above this doorway was placed a bust of Francis I, matching in its full dimensions the painted full length image of the king on the outside visible to all who used the south terrace when the gallery was not accesible and by all who were in the Cour de la Fontaine enjoying the outdoors in a variety of ways as appears in the small view of this court within the gallery.

Guillaume brings up Zerner’s observation that the stucco figures flanking the oval painting in the center south bay are done in very high relief while the stucco relief in the adjacent bays with the major subjects of Cleobis and Biton (Fig.P.22, V S a) and the Death of Adonis (Fig.P.22, III S b) is low, thus emphasizing the central position of the bay for which the Nymph of Fontainebleau was planned. This high relief also appears at the far west on the south side with the large satyrs flanking the Enlightenment of Francis I (Fig.P.22, VII S a) and the far east but on the north side with the beautiful nude young man and woman alongside the Venus and Minerva (Fig.P.22, I N a). This correspondence almost certainly indicates that the destruction of the south cabinet and the creation of the decoration for the center bay on the south side were determined very early in the scheme of the decoration of the Gallery of Francis I.

As Zerner clearly demonstrated, this scheme is remarkably complex and ingenious. Given what was offered to Rosso to decorate when he arrived in 1530, a gallery and four cabinets, it was the spaces that he first took account of. At the same time, it was their decoration that he needed to foresee. It was very likely his idea to reduce the number of four adjunct spaces—three cabinets and a chapel—to one, the north cabinet. While the foundations of the cabinets were readily built, that for the south cabinet was also part of the series of masonry arches housing the new kitchens and larders. Rosso may well have stopped the construction of the south cabinet well before it was well along, knowing quite soon that he wanted a center wall in his gallery, and at the same time saw the opportunity to unify its south façade.

The re-designing of the south façade and the concomitant changes to the scheme of the decorations of the gallery would seem to be due to Rosso. They gave to the original conception of the building, inside and out, a new symmetrical and centralized strength that cannot be attributed to Le Breton.7

The architectural role that can be suggested for Rosso in the design of the Gallery of Francis I was one of modifications to a building the construction of which had been begun and perhaps largely completed by the time that he arrived in France. But these modifications made the building significantly different from the one that Rosso first encountered. The changes involved spaces and the articulation of a façade and were hence the result of intrinsically architectural decisions.8

1 It may be that the chapel was then planned to be placed above the new Chapel of Saint Saturnin in the Cour Ovale. This upper chapel was called the Chapelle Haute or the King’s Chapel (see A.4).

2 Dan, 1642, 34, 36-37, and Pressouyre, 1974, 18, 23, ns. 36, 37. Dan would have meant the floor of the terrace and its parapet. The small exterior view of the gallery under the Venus and Minerva in the gallery shows a continuously closed parapet, not one made of balusters supporting a ledge. The arches of the kitchens and larders below are walled in about halfway up the piers; they are completely open in Du Cerceau’s drawn view and etched views of 1579. The parapet of the terrace remains completely closed but now divided into sections by piers that follow the line of the pillasters below. In a tapestry cartoon (Fig.Barberini Tapestry Cartoon reversed) showing the entire Cour de la Fontaine with the west building behind the Pavillon des Poêles completed and hence dating after 1560 but before 1579, the date of Du Cerceau’s prints, the parapet appears continuous and undivided by piers. The center window of the Gallery of Francis I is already a blind window but the dormer above is set within a peaked roof as in Du Cerceau’s engraving and in Rosso’s small painting. The cartoon in the Barberini Collection in Rome was brought to my attention by Candace Adelson.

3 The façade was refaced under Henry IV early in the seventeenth century (see Pressouyre, “Cadre architectural,” 1972, 18-19, and Pressouyre, 1974, 36).

4 The shape of the baldachin resembles the kind that appears as the Temple of Priapus in a woodcut illustrating The Dream of Poliphilus published in Venice in 1499 (Fig.Temple of Priapus), although it cannot be determined out of what materials the Fontainebleau structure is made (see Golson, 1975, 234, 235, Fig. 5).

7 Prinz and Kecks, 1985, 356, 417, stated that Pierre Paul, “dit l’Italien,” was responsible for the plans at Fontainebleau, as shown by the Comptes (Labordes, I, 1877, 59-60). But how this can be related to Le Breton’s activity and the appearance of the buildings is not indicated. Pierre Paul died 28 December 1535.

8 Geymüller, 1898, 159, thought that Vasari’s comment, following the remark that Rosso was made “capo generale” of all the buildings at Fontainebleau, that he was given the gallery and made “di sopra non volta, ma un palco overro soffittato di legname, con bellissimo spartimento” (Vasari-Milanesi, V, 167), indicated that he was the architect of the entire gallery. But the specification of 1528 for the gallery already indicates such a ceiling. Geymüller also thought that the present exterior appearance might be due to Rosso, but this façade is certainly later (see Pressouyre, “Cadre Architectural,” 1972, 18-19, and Babelon, 1989, 690, no. 261). There is no evidence to indicate that the original façade, visible in the small exterior view in the gallery, was designed by Rosso, although I suggest that he had a hand in the redesigning of the façade when the South Cabinet was removed, and a painted seated figure occupied the center bay.

Geymüller further thought that the Grotto of the Jardin des Pins might have been designed by Rosso (as suggested by Boitte, the architect of the château at the end of the nineteenth century). But this certainly is not true (see Claude Lauriol, in EdF, 1972, 482).