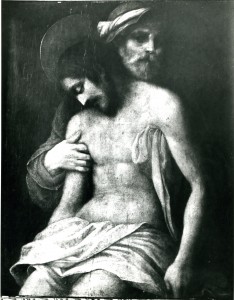

Baltimore, Dr. George Reuling Collection (formerly).

Panel (as seems evident from the photograph), dimensions unknown (but see other versions below).

PROVENANCE: Farinola Collection, as Andrea del Sarto (from a note on the photograph at I Tatti).

LITERATURE:

Berenson, 1932, 495, as Rosso, and as in the Reuling Collection.

Berenson, 1963, I, 495, as Rosso (?), and as formerly in the Reuling Collection.

(A note on the photograph at I Tatti gives Rosso or Puligo).

Carroll, 1971, 26, 28, as possibly related to a lost panel painting by Rosso mentioned by Vasari, executed between the end of 1515 and 1521.

Cox-Rearick, 1989, 63 and Fig. 27, 66-67 and n. 90, as Rosso? (after).

Forlani Tempesti, 1992, 101, n. 19.

The composition of the Reuling painting is known also from five other paintings in Ajaccio, Florence, New Haven, Paris, and Siena, and from a drawing in the Uffizi:

Ajaccio, Musée Fesch, MFA 852.1.705, as Shop of Baccio Bandinelli. Oil on panel, 86 x 72 (Fig.RP.1, Ajaccio). PROVENANCE: Rome, Cardinal Fesch, bequeathed to the museum in 1839, acquired in 1842 (website catalogue, with color reproduction). From the reproduction, color close to that of the Siena painting. In addition, there are two embroidered bands in yellow tan on the cloth covering Christ’s loins and upper legs matching the single band on the cloth bound around Nicodemus’s hat. The picture was brought to my attention by Richard Pardo, Paris.

Florence, Private Collection (from Richard Pardo, Paris, 2005, who commented in his letter that there are even more painted copies than the five listed here).

New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, 1871.80. Oil on canvas, 72.9 x 59 cm. (Fig.RP.1, Yale). PROVENANCE: Purchased from James Jackson Jarves, 9 November 1871. LITERATURE: Russell Sturgis, Jr., Manual of the Jarves Collection, New Haven, 1868, no. 93, as probably by a pupil of Andrea del Sarto, perhaps Puligo. Osvald Sirén, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection belonging to Yale University, New Haven, 1916, 201-202, as probably a copy after Sogliani. Carroll, 1971, 26, 28. Forlani Tempesti, 1992, 101, n. 19.

The file card at the gallery notes that the execution is later than Sogliani and that the picture is possibly a copy of a work by him. A note on a photograph of the Reuling painting suggests Correggio for the Yale painting.

The picture is so heavily varnished and so dark that it is now impossible to distinguish its colors.

Paris, Galerie Pardo (Fig.RP.1a), formerly Paris, A. Boulanger Collection (Fig.RP.1b; Giraudon photograph 35467 made in 1936, as by Andrea del Sarto). Panel, 77 x 59 (from Richard Pardo, Paris, 2005). LITERATURE: Carroll, 1971, 26, 28. This picture was kindly brought to my attention by Janet Cox-Rearick. Forlani Tempesti, 1992, 101, n. 19.

Siena, Pinacoteca, no. 464 (Fig.RP.1, Siena). PROVENANCE: Siena, Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala. LITERATURE: Cesare Brandi, La Regia Pinacoteca di Siena, Rome, 1933, 107, as by Giovanni Antonio Lappoli. Enzo Carli, Guides della Pinacoteca di Siena, 1958, 107. Carroll, 1971, 26, 27, Fig. 14, 28. Forlani Tempesti, 1992, 48, 101, n. 19, Fig. 12, as perhaps by Giovanni Antonio Lappoli.

The picture is almost monochrome, an aspect enhanced by its old varnish. Christ’s body is very gray with a brown-yellow cast;

his hair and beard are reddish brown; his loin cloth gray with bluish shadows. Nicodemus’s flesh is brownish orange and slightly red on his right cheek; his beard is gray. He is dressed in a very dark red robe and a brownish turban, with a gray-white folded band at the left and a red fold over his forehead. The cloth he holds under Christ’s left arm is yellow ochre. The background is very dark brown.

Enzo Carli informed me that from 1872 until the time of Brandi’s catalogue it was attributed to Matteo Lappoli.

Florence, Uffizi, 1498S, as School of Alessandro Allori (Fig.RP.1, Florence, Drawing). Black chalk, 22.1 x 18.7 (maximum). LITERATURE: Santarelli, 1870, 116, no. 6, as School of Alessandro Allori. Carroll, 1971, 26, 28.

I had once thought, following Berenson’s suggestion about the Reuling painting, which I know only from a photograph, that this image might go back to a lost original panel painting by Rosso that Vasari said he painted for the Lord of Piombino; this would probably have been around 1520 (see L.15). But this now seems unlikely as there are no stylistic elements that sufficiently suggest Rosso’s art to warrant an attribution to him, especially from the time immediately preceding his stay in Volterra. It is also improbable that a picture by him in Piombino should lead to the number of versions that still exist of this picture. Rosso had also done very early in his career a Dead Christ in fresco (L.4), but this lost work in a tabernacle in a villa outside Florence would hardly have been so extensively copied. It is true that a drawing could have served as the source of these images and that Rosso may have created another, otherwise unrecorded, image of this subject. But the style of the image in its various versions still does not compel an attribution to him.

Cox-Rearick suggested in 1989 (see above) that the figure of Nicodemus is a self-portrait (or suggested that in such pictures he is often a self-portrait), but she did not pursue the implications of this idea in this particular case. The physiognomy of Nicodemus is very much the same in the Reuling, Ajaccio, Pardo-Boulanger, and Siena paintings. But that it is Rosso’s cannot be proved. The full moustaches and the beard could be related to those of Rosso’s portrait in Vasari’s Lives of 1568. They are reddish brown in the Siena painting, but not necessarily the color that gave Rosso his name. In other respects, however, Vasari’s portrait does not show any resemblance to the head in these paintings of the Dead Christ.

The configuration of the drapery on Christ’s lap relates the Reuling, Pardo-Boulanger, and Siena pictures, of which the first two are of significantly higher quality than the last. The version in Ajaccio shows bands of decoration on this drapery and on that wound around Nicodemus’s hat. The drapery of the Yale picture is related to that in the Uffizi drawing. The Pardo-Boulanger and Ajaccio paintings are most similar. Nicodemus’s physiognomy in the drawing is somewhat different from what appears in the paintings, showing the figure with longer moustaches.

There is also a drawing of this subject that has been attributed to Rosso:

Dresden, Grahl Collection (formerly). Red chalk, 24.1 x 18.7 (Fig.RP.1, Dresden, Grahl, Drawing).

The drawing can be attributed to Salviati and dated in the late 1530s (see Carroll, 1971, 26-28, Pl. 12, with full bibliography, to which can be added its provenance from Christie’s information to Sale 2364, 7 December 1999, Cerchio di Rosso Fiorentino: H. Beckmann, L.2756a. Drawing was sold). Its composition is different from that of the other paintings and drawings but shares certain elements with them: the length of Christ’s body, his placement on a ledge, a turbaned Nicodemus supporting him from behind (who seems not to be a portrait), and a somewhat limited space and format. While I once thought that this drawing might be derived from Rosso’s lost picture made for the Lord of Piombino, I do not see now that this can be said with any certainty. The drawing seems to reflect Bandinelli’s drawing style and it is this resemblance that connects it also to Rosso’s art of around the time of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece of 1518 when, or shortly before, Rosso and Bandinelli seem to have shared aspects of their styles. Compositionally, Salviati’s drawing is not specifically related to the tapestry in the Palazzo Pitti (Fig.Tapestry, Pitti),1 but there is a resemblance in the extent of Christ’s body, in its support by a figure behind him (who does not resemble the figure in the drawing), in the ledge on which Christ sits, and in the restricted space and format of the compositions. Forlani Tempesti, 1992, 98, 101, n. 18, Fig. 11, as not by Salviati and possibly by Giovanni Antonio Lappoli, and, without excluding that the composition goes back to one by Rosso, states that this origin does not seem necessary.

Although nothing conclusive can be said at this moment about the paintings and the Uffizi drawing showing the Dead Christ Supported by Nicodemus, the evidence surely indicates an image of some devotional importance. This image has correspondences to a drawing that has been attributed to Salviati and to a tapestry designed by him. It is quite possible that the five paintings may also be related to Salviati, perhaps following the Grahl drawing. The Pardo-Boulanger picture requires further study, along with the Ajaccio picture, whose attribution to the Shop of Bandinelli further suggests the ambiance in which the original image was created. Perhaps one of these two paintings is that picture.