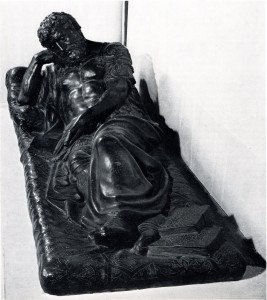

Paris, Louvre, M.R. 1680 and N. 15092.

Bronze. 56 x 167 x 65.4.

The statue was originally partially gilt.

Fig.Sculpture a

Fig.Sculpture b

PROVENANCE: From his tomb on the left side of the nave of the church of the Cordeliers, Paris. Musée des Monuments français, 7 Frimaire an II (27 November 1793). Entered the Louvre in 1816.

LITERATURE:

Dimier, 1900, 123 and n. 4, as of 1535, and certainly Florentine, perhaps by Rustici or by his pupil Lorenzo (Laurent) Naldini (Renaudin or Regnauldin).

Adolfo Venturi, “Miscellanea,” L’Arte, VII, 1904, 471, Fig., 472, attributed the statue to Prospero Spani, il Clemente.

Roy, 1921 (1929), as by Rosso, and related to the model for a tomb made by Rosso and mentioned in a document of October-December, 1531.

Kusenberg, 1931, 131, as not by Rosso.

Blunt, 1953, 40, n. 27, found Roy’s argument convincing and thought the tomb may have been designed by Rosso.

Carroll, 1966, 179, n. 48, as not by Rosso.

Laskin, 1971, 256, as not by Rosso.

Jacques Thirion, in EdF, 1972, 402-403, no. 552, 404, Fig. (with earlier bibliography), as attributed to Rosso, with reservations, and as not sure that it was executed in France.

Raggio, 1974, 75, as around 1542, far from Rosso and from France, and reminding her of Ammanati.

Ulrich Middledorf, “On Some Portrait Busts Attributed to Leone Leoni,” BM, 117, 1975, 88, as by Rustici, “even if Rosso furnished the all-over design.”

Michèle Beaulieu, Description raisonnée des sculptures du Musée du Louvre, II, Renaissance française, Paris, 1978, 165-167, no. 255 (with earlier bibliography), as attributed to Rosso, with reservations.

Carroll, 1987, 35, n. 99, as not by Rosso.

One time attributed to the fictitious Paul Ponce, the author of this statue has been variously suggested as Rustici, Lorenzo Naldini, Prospero Spani, Rosso, Ammanati, and again Rustici. Beaulieu, remarking on its fine chasing, said it brought to mind the Fontainebleau artists’ studios under the direction of Pierre Bontemps. He also pointed out that the tasseled pillow bent by the weight of the figure’s elbow is a motif frequently found in Rosso’s paintings. While such pillows are found in Rosso’s Pietà in the Louvre and in his Loss of Perpetual Youth in the Gallery of Francis I, so, too, is one found in Primaticcio’s Danaë in the same gallery, and in many other French pictures and statues of the sixteenth century. Rosso’s pillows do not seem to be affected by anything weighing upon them.

There is no direct evidence that connects this tomb effigy to the document of October-December, 1531, referring to a model for a tomb requested verbally by Francis I (see L.37). Roy’s arguments prove no such relationship. The inscription on the tomb, while it mentioned the count’s association with Francis I, indicated that the tomb was erected by Alberto Pio’s heirs, not by the king. Furthermore, Roy made no attempt to support his hypothesis with any stylistic comparisons. There is an abundant amount of sculpture designed by Rosso in the Gallery of Francis I, and although Rosso may not actually have modeled any of it, the sculpture surely bears the imprint of his imagination and invention. The tomb effigy does not look like any of the sculpture in the gallery, nor like any in other works by him, such as the Design for an Altar (Fig.D.38a) or the Design for a Tomb (Fig.D.81a). It also bears no resemblance to Rosso’s Saint Paul and Saint Peter, an engraving attributed to Boyvin (Fig.E.8a), which may have been designed as sculpture between 1530 and 1532. The whole formal conception of the bronze figure in space appears totally at odds with Rosso’s planar mode of invention.

The surface decoration of the pillow and pad on which the figure lies very much resembles some of the patterns in Francesco Pellegrino’s La Fleur de la Science de Pourtraicture of 1530, which, it might be pointed out, was sold “Au logis de monseigneur Le Conte de Carpes” (Fig.Pellegrino, Pattern; Fig.Pellegrino, Pattern 2).1 This kind of decoration is found nowhere in Rosso’s art. Pellegrino was Rosso’s most highly paid assistant in the Gallery of Francis I and worked primarily as a stuccoer. He was a Florentine. The likelihood is that he was a sculptor before Rosso used his talents in the gallery. He was a friend of Rustici, who was introduced to Francis I by Pellegrino.2

I cannot say who made this statue. Prospero Spano does not seem likely to me, as he did not to Beaulieu. The attributions to Rustici and Ammanati need further time to resolve, as does the association with Bontemps. I venture to add Pellegrino’s name as a possible candidate.