c. 1536

Paris, Ensba, no. 340 (formerly no. 34886).

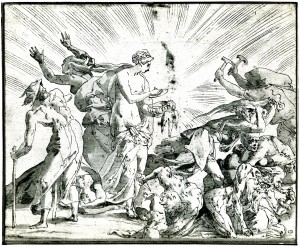

Pen and ink and wash over traces of black chalk, 24.2 x 29.3; somewhat faded and stained at the top center. Inscribed in ink at the lower left: maitre Roux.

PROVENANCE: Armand Valton; given to the Ensba in 1908.

LITERATURE:

Notice, Fontainebleau, 1921, no. 124, as Rosso.

Lavallée, 1930, 22, as Rosso.

Kusenberg, 1931, 137, 144, no. 63, 148, under no. 10, Pl. LXXVII, as Rosso, 1530-1540.

Art Italien, 1935, 39, no. 133, as Rosso, and made at Fontainebleau between 1530 and 1541.

Berenson, 1938, no. 2458C, as Rosso.

Lavallée, 1948, 22, as Rosso.

Barocchi, 1950, 108, 128, 131, 173-174, 214-215, Fig. 192, as Rosso, from the French period.

Bologna and Causa, 1952, 60, as Rosso.

Panofsky, 1956 (1965, 34-54, 79, 142, 145-146, Fig. 16), as Rosso, and as dating from 1534 or later because of the appearance of the crow, which first appeared as a symbol of Hope in the second edition of Alciati’s Emblemata, Augsburg, 1534, or from 1536 or later if Rosso used the third edition, Paris, 1536; also as done in connection with the Ignorance chassée [Enlightenment of Francis I] fresco in the Gallery of Francis I, either as a stucco relief, or more probably for a section of the fresco itself.

Panofsky, 1958, 117, Fig. 5, 161-164, 165, n. 13, as in Panofsky 1956 (1965).

Renaissance Italienne, EdB-A, 1958, no. 46, as Rosso and made at Fontainebleau after 1530.

Carroll, 1961, 446, 453, as Rosso, from his French period. Berenson, 1961, no. 2458C, as Rosso.

Carroll, 1964 (1976), I, Bk. I, 247-252, 260, II, Bk. II, 387-390, D.43, Bk. III, Fig. 108, as Rosso, ca. 1534 – ca. 1536.

Béguin, in Seizième Siècle… Peintures et Dessins, 1965-66, 202, Fig., 203, no. 249, as Rosso, and as generally dated 1534-1535.

Carroll, 1966, 176, 179, as Rosso, and as probably done between 1534 and 1536.

D. Rondorf, Der Ballsaal im Schloss Fontainebleau zur Stilaeschichte Primaticcios in Frankreich, Bonn, 1967 (Thesis), 348 (from Béguin, in EdF, 1972).

Rome à Paris, 1968, no. 246, as Rosso and as made for the Gallery of Francis I.

Perez Sanchez, 1969, 118, under no. 604, as Rosso (see below). Zerner, 1969, under A.F.22, as Rosso.

Béguin, RdA, 1969, 105, mentioned.

Béguin, 1970, 9, 89, Fig. 12, as Rosso, and as generally dated 1534-1535.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, 1970, 498, Fig. 187.

McAllister Johnson, in “Galerie,” RdA, 1972, 162, Fig. 27, 171, n. 94, states that it is difficult to say that the drawing is related to the Gallery of Francis I.

Béguin and Pressouyre, 1972, 126, related McAllister Johnson’s opinion as above, adding his opinion that thematically and stylistically it is related to the relief of Rage and Madness under the Centaurs and Lapiths fresco, and that the figure of Pandora resembles Venus in the Venus and Minerva scene.

Béguin, in EdF, 1972, 184, Fig., 185, no. 209, as Rosso, and generally dated 1534-1535.

Raggio, 1974, 74, as Rosso.

Gibbons, 1977, 56, under no. 150, as Rosso.

Brugerolles, 1984, 95, no. 103, and Pl.

Lévêque, 1984, 167, Fig., as Rosso.

Carroll, 1987, 11, 298-301, no. 95, with Color Pl.

Joukovsky, 1987 bis, 12, n. 33 (1992, 70. n. 1), noted the analogy with the Expulsion of Ignorance in the Gallery of Francis I.

Joukovsky, 1988, 24 (1992, 103), mentioned the figure with the hammer as in the Death of Adonis in the Gallery of Francis I.

Franklin, 1988, 326, no. 92, believes it may be a copy. (Franklin tells me he now thinks it is an autograph drawing.)

Carroll, 1989, 27, Fig. 47.

Miller, 1992, 111, 112.

Brugerolles and Guillet, 1994, 36-40, no. 14, Color Pl. 37, as Rosso, and as related to the Expulsion of Ignorance (or Francis I trampling upon the Demons of Ignorance) in the Gallery of Francis I.

Béguin, 1994, 271, wrongly as in the Louvre, as perhaps a preliminary study of the Expulsion of Ignorance in the Gallery of Francis I, as suggested by the Panofskys, its theme perhaps also expressed in the Semele fresco of the North Cabinet of the gallery: “the fatal consequences of asking too many questions.”

Béguin, 1995, 192, as Rosso.

The traditional attribution of this drawing to Rosso, which, so far as the inscription on it would seem to indicate, pre-dates this century, has only once been questioned (see below). It has always been dated in the artist’s French period. As Barocchi and the Panofskys pointed out, the drawing is figuratively and compositionally very similar to Rosso’s Enlightenment of Francis I (Fig.P.22, VII S a) in the Gallery of Francis I, a fresco that appears to have been designed in 1535 or 1536. Even more, the drawing resembles the approximately contemporary Allegorical Scene of Rage and Madness in stucco beneath the Combat of Centaurs and Lapiths fresco (Fig.P.22, I S c). The extravagant beauty of this drawing – the swiftly moving pen lines, the clarity of the washes, and the resulting marvelous effects of blinding light and dramatic energy – emphatically affirms that the inventor of this fantastic scene is also its draughtsman. There is no other autograph drawing by Rosso that quite meets the terms of the handling of the Pandora and Her Box, but the Throne of Solomon (Fig.D.34) shows, more methodically employed, the same kinds of lines, hooks, rows of short strokes, and superimposed washes. The draughtsmanship of the Pandora and Her Box can quite easily be seen to be an extension, albeit an extraordinary one, of that of the Aretine drawing. But this transformation is also recognizable in the change from the rather ritualistic character of the composition of the Throne of Solomon, and also of the more emotionally charged Madonna della Misericordia of the same time (Fig.D.35a), to the energetically acted-out and dramatically pictorialized scene of the nevertheless equally allegorical Pandora and Her Box. Franklin’s reservations of the autograph status of the drawing should be dispelled by comparing it with the quality of the several copies of it (listed below).

The Panofskys’ dating of the drawing not before 1534 or not before 1536, depending on which edition of Alciati’s Emblemata Rosso knew, provides at least the indication that the drawing is not an early French work by him (but see below). This is borne out by the style of the drawing, which differs so much from the Mars and Venus of 1530 (Fig.D.42a), the Judith of 1530-1531, engraved by Boyvin (Fig.E.7), and the early version of the Sacrifice made for the Gallery of Francis I, which seems to date no later than early 1534 (see under P.22, VII N). The dramatic interpretation of the theme of the drawing resembles that of the Enlightenment of Francis I, the Combat of Centaurs and Lapiths (Fig.P.22, I S b), and the Revenge of Nauplius (Fig.P.22, III N a) in the gallery, all of which appear to have been designed in 1535 or 1536. Even more, the Pandora and Her Box looks like the Death of Adonis (Fig.P.22, III S a) and the final version of the Scene of Sacrifice (Fig.P.22, VII N a), designed probably between August and November 1536. Those frescoes and the drawing show the same kind of dramatic frenzy and similar turnings and foreshortenings of the figures. Consequently, the Pandora and Her Box is probably datable around 1536. It does not appear related to any work by Rosso that can be placed later in his career. The dating of the drawing around 1536 can be supported by stylistic evidence without reference to its association with the editions of Alciati’s Emblemata.

The Panofskys suggested that the drawing may have been made to find its place on the wall in the gallery where now appears the Enlightenment of Francis I, either as a subsidiary scene or, more likely, as the subject of the principal fresco. As a substitute for the Birth of Venus relief at the bottom of this wall, the Pandora and Her Box is unlikely, for the subject of Venus is so appropriate to the iconography of other parts of the gallery. If the Pandora drawing was designed for the principal fresco it would, on stylistic grounds, have had to have been made at the same time as the Enlightenment of Francis I. In other words, they would have been alternative possibilities. This could have been the case, but the subject of the executed fresco again appears iconographically related to other parts of the gallery, to the Venus and Minerva scene in particular, and the Pandora and Her Box does not appear an adequate substitute. McAllister Johnson related it “par le sujet et le motif” to the Scene of Rage and Madness beneath the Combat of Centaurs and Lapiths, and saw that the figure of Pandora recalls Venus in the Venus and Minerva fresco (Fig.P.22, I N a), but rejected an association with the Enlightenment of Francis I. There is no certainty that the drawing was intended for the Gallery of Francis I, but it is possible that it was designed for it, but, if so, then probably for a subsidiary position. As the rays emanating from the area of the box would not seem translatable in stucco but could be interpreted in paint, the placement of this scene could have been under the Venus and Minerva, where there is now a painted view of the château. Here it could be related iconographically to the fresco above, to the Enlightenment of Francis I, and to the Combat of Centaurs and Lapiths.

The old woman at the lower right was identified by the Panofskys as Envy eating her own entrails. However, what she bites on seems to be the head of a snake with its mouth open wide. All of the copies (see below) render this detail in the same way or even more specifically as a snake’s head; in Fantuzzi’s etching (Fig.E.79a; see below), it is clearly a snake, the length of whose body is covered with scales. Ripa, Iconologia, Rome, 1603, 241-243, describes Envy as an old hag and as eating her own entrails, but he also indicates that she can be shown with a snake biting her left breast also to signify that envy feeds upon itself. In the sum total of its characteristics, and in relation to the other figures in the drawing, the figure at the lower right is most likely Envy. Either Rosso shows an entrail as he does to give it a serpentine aliveness, or in showing an entrail-like snake being bitten by the old woman he gives evidence of a certain degree of perhaps intentional complexity in the iconography of the figure.1

Béguin, Revue de l’Art, 1969, 105, believed that the bird in the drawing and in Fantuzzi’s etching of this scene is a dove symbolizing Peace; Barocchi, 1950, 215, thought also that the bird in the drawing is a dove. The bird in the etching has a broad tail and full wings as well as rather fluffy feathers depicted all over it. It does look like a dove. But in the drawing it has a tapering tail and in general a more sleek appearance. However, it does not necessarily look like a crow. It is also not black, although this may not be a significant factor in a drawing that is not colored and where all shading is used to depict shadows. The Panofskys identified it as a crow because of its connection with Hope in Alciati’s Emblemata of 1534 and 1536, and in later editions; this bird would then have been used for the same symbolic meaning in Rosso’s Pandora. Although the species of the bird in Rosso’s drawing cannot on its appearance alone be identified, the Panofskys’ argument would seem to make it likely that it is a crow. But if not a crow, it could, as a dove, symbolize Peace, although in this case it cannot solely be related to Alciati’s Emblemata. Fantuzzi may not have wholly understood the symbolism of the bird, but he seems to have described it as a dove.

COPIES, DRAWINGS: Gijon, Instituto Jovellanos, no. 604 (destroyed) (Fig.Pandora, Gijon). Pen (and wash on the hair of the central male nude at the bottom?), 20 x 27. Inscribed in pencil on the verso: Di Jacopo… onoggino. Moreno Villa, 1926, 72-73, no. 604, as eighteenth century French, by a follower of La Fage. Perez Sanchez, 1969, 118, no. 604, Pl. 230, as a copy of Rosso’s drawing. Béguin, in EdF, 1972, 185, under no. 209, as a copy after Rosso (and wrongly as in the Academia San Fernando, Madrid). Brugerolles, 1984, 95, under no. 103 (also wrongly as in Madrid). Carroll, 1987, 301, n. 1, under no. 95.

This copy is without the rays emanating from the area of the box.

Formerly Villa di S. Michele, near Novellara. For a drawing of Pandora that might be related to Rosso’s drawing, but showing serpents, perhaps as in Fantuzzi’s etching, see under E.79.

Paris, Ensba, no. 341 (formerly no. 22899) (Fig.Pandora, Beaux-Arts). Pen and ink and wash, 24.3 x 28.8. PROVENANCE: Le Soufaché Collection (inscription on mount). LITERATURE: Kusenberg, 1931, 148, no. 10, as a copy of Rosso’s drawing. Béguin, in Seizième Siècle… Peintures et Dessins, 1965-1966, as a copy after Rosso. Béguin, in EdF, 1972, 185, under no. 209, as a copy after Rosso. Brugerolles, 1984, 95, under no. 103. Carroll, 1987, 301, n. 1, under no. 95. Brugerolles and Guillet, 1994, 37, Fig., 40, n. 13, as a copy of Rosso’s drawing.

An accurate copy of Rosso’s drawing, somewhat schematized, but with a few details slightly elaborated. There are also six long snakes radiating from Pandora’s box along with the lines indicating the rays of light.

Paris (summer, 1959), Paul Prouté et son fils (Fig.Pandora, Prouté). Pen and ink and wash, 24 x 28.8; damaged in the lower right corner and repaired; wm. similar to Briquet 13.082. Inscribed in ink in the lower left corner, but partly effaced: Rosso. PROVENANCE: Louis Deglatigny (Lugt 1768a). This drawing was kindly brought to my attention by Bernice Davidson. (Photograph: N. Mandel, Paris). LITERATURE: Carroll, 1987, 301, n. 1, under no. 95.

An accurate copy of Rosso’s drawing with the washes somewhat simplified.

Princeton, Princeton University Art Museum, no. 48.699 recto (Fig.Pandora, Princeton). Pen and ink, 24.7 x 29.6; slightly stained. Inscribed in ink at the lower left: polidoro, and in pencil across the bottom: A. 22 Polidoro da Caravaggio / (verso Polidoro) / Purchased 1934, and at the lower right: Pandora; in pencil on an added piece of paper at the lower left: A 22 33. LITERATURE: Gibbons, 1977, I, 55, no. 150 recto, II, Fig., 105r., as by Girolamo da Carpi. Carroll, 1987, 301, n. 1, under no. 95.

A rapid sketch after Rosso’s drawing or after a copy of it, without the rays emanating from the area of the box.

PRINT: Fantuzzi, E.79 (Fig.E.79a). Etching. This print shows the scene in reverse. The rays in the drawing are missing and there are seven snakes rising as a group from the area of the box. (Their size and arrangement are not related to what appears in the ENSBA copy of Rosso’s drawing.) The bird has a broad tail and has feathers specifically depicted over its entire surface, perhaps suggesting a dove more clearly than in Rosso’s drawing.

1 In Giulio Romano’s drawing of Proserpina Entrusting Psyche with the Vase containing Beauty (Louvre 3492; Hartt, 1958, I, 297, no. 171, II, Fig. 270), the figure of Envy at the far right also seems to show a conflation of entrails and snakes, although the smoothly curved forms look more like snakes. In the anonymous etching of the drawing (Zerner, IB, 33, 1979, 349), scales have been added to specify snakes. The drawing in Frankfurt of Meleager Offering the Head of the Calydonian Boar to Atalanta (Fig.RD.16) shows a similar conflation, which remains the same in Fantuzzi’s etching (Fig.RE.17), that is, without the explicit addition of scales. However, in none of these works are the forms so irregular and gnarled to suggest entrails as they do in Rosso’s Pandora drawing.