Influenza virus and a few other viruses have segmented genomes. Most viruses carry their genetic information on a single piece of DNA or RNA, but influenza has 8 pieces. You can think of this as analogous to our chromosomes: we have our 20,000 genes spread out over 23 chromosomes. Each chromosome is a separate piece of very long DNA. Influenza has 8 genome segments (we don’t call them chromosomes for viruses) to encode its 11 genes.

Having a segmented genome presents a unique problem for the virus. At the end of a viral replication cycle, new virus particles must be assembled from the individual components. That usually involves assembling a capsid with the genome packaged inside, and picking up an envelope. Its complex enough to get all the components together in the right place, in the right amounts, at the right time. Influenza has the problem of needing to get 8 pieces of RNA packaged instead of just one. And it cant be any 8, it has to be one of each, otherwise the virion would not carry a complete set of instructions to successfully execute the next round of infection.

So influenza must somehow collect its 8 segments to package into the virion. When I took virology as an undergrad, I remember very clearly this problem because nobody knew how it worked. What? A major step in the replication of a major virus and we don’t know how it works? Virology suddenly seemed so exciting because there were major unanswered questions. Apparently its a hard one to answer since the details are still unknown but a strong picture is emerging from a growing body of research.

Two models have been proposed for how influenza assembles its 8 RNA segments. One, the random incorporation model, suggests that 8 randomly selected viral RNAs are packaged. This would result in most particles being defective, since the chance of selecting one of each is quite low. I’ve never been fond of this model, as it just seems too inefficient. The selective incorporation model, on the other hand, proposes that during the assembly process there is some way to select one of each genome segment.

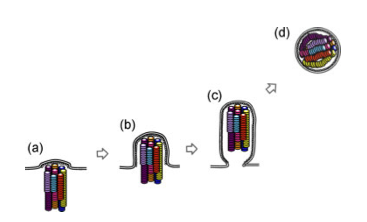

A few studies over the last few years have advanced our understanding of the process. First, some very high quality electron microscopy revealed that the genome segments are packaged in a very specific arrangement with 7 segments in a circle surrounding 1 in the middle. Think of each segment as a dowel, bunched up lengthwise. Each segment is a different length, and each of the “dowels” in the electron micrographs appear to be different lengths, suggesting that each one is unique.

Another study used a single molecule fluorescent labeling technique to show that one and only of each of the segments is packaged into the virion. Using rather amazing microscopy, in which a single RNA molecule in a single virus particle can be detected with a fluorescent probe, they were able to show that the majority of virions carry one copy of each of the 8 segments. Several other studieshave identified unique packaging signals in the nucleic acid sequence of each genome segment. These packaging signals would serve to associate the genome segments with each other and with other components of the assembling virion.

Each one of these studies has potential problems that make them, on an individual basis, insufficient to nail the coffin shut on the random incorporation model. For example, the 7+1 arrangement is only seen in a small fraction of virions. Is it because only some have that arrangement or is it that the preparation of the samples for electron microscopy distorts some particles? This question of how influenza packages its genome serves as a terrific example of the scientific process and the necessity to generate a large body of work to figure out what may seem like a simple question. In class, we talk about designing experiments to test a hypothesis, but tend to see examples of one experiment that really nailed it. It doesn’t usually work that way. You typically need many different experiments, approaching the problem in different ways, because any single experiment could have a valid critique that weakens the conclusion. The whole body of work must be considered, and in this case the body of work appears to be supporting the selective incorporation model.