Fans of Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone will know Ebola virus and Marburg virus as ones that causes their victims to die a horrific death, bleeding from every opening and turning organs into a bloody pulpy mess. Ebola outbreaks occur sporadically in central and west Africa, and despite extensive efforts, its still not known where the virus comes from. The best evidence is that bats carry the virus, and contact with bats or bat excrement in caves sparks the outbreaks. Ebola RNA has been detected in bats, but no one has been able to find live virus in bats.

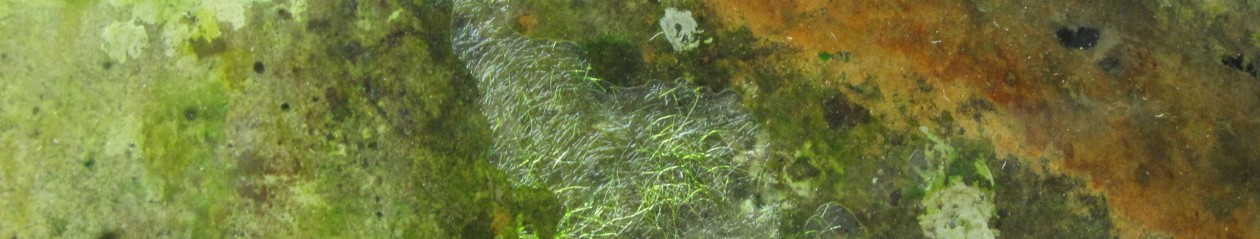

But now a close relative of Ebola and Marburg viruses has been discovered in bats in Spain. And unlike Ebola and Marburg, which don’t cause disease in bats, it is possible that this newly identified virus is killing the bats. A recent bat die off in Spain killed several bat colonies in a little more than a week. So researchers searched for viral sequences in the bats and identified an new filovirus, and called it Lloviu virus, after the cave in which it was found. They found the same viral sequence in other caves that experienced die offs, and could not find evidence of the virus in healthy bats.

This finding is significant for several reasons. It is the first detection of a naturally occurring filovirus outside of Africa and The Philippines. The bats in Spain do not overlap with the known geographic range of Ebola and Marburg viruses so its unlikely that it would have been picked up there. There have been bat die offs across parts of western Europe, and it will be interesting to see if Lloviu virus is found at all these locations.

Also, it might be making the bats sick. The key word being might. In my class called “Microbial Wars” we have discussed Koch’s postulates and hopefully my students will recognize that these are far from fulfilled. Live virus has not yet been isolated from diseased animals, only detection of the viral genetic material. Researchers will need to demonstrate that experimental inoculation of bats with live Lloviu virus will cause the expected disease.

Cueva de Lloviu is frequented by tourists, so its possible that many people have been exposed to the virus without ever developing disease. So this is not a human health concern but it is an important discovery that may help us understand filoviruses better, especially with respect to their ecology.