Since its inception, the World Wide Web has gradually evolved in order to accommodate user’s needs, particularly in regards to input and output of text and images. What started as very rudimentary displays based on the ASCII character set, has now become expanded, standardized systems like Unicode, HTML4 (and hopefully soon HTML5), CSS and all other web standards in use today. But what about the most universal of human languages, mathematics? The evidence tells us that the ability to display mathematical expressions on the web has evolved very slowly, and is very far from reaching a point of widespread adoption, which is somewhat surprising considering the great amounts of potential users around the world.

Even though a standard for math on the web, MathML, has existed since 1998, with its latest version MathML 3.0 adopted very recently, it is a tool with remarkably little use on the web. There are many reasons for this: the reluctance of users to learn a new coding language from scratch, the availability of “user-friendly” tools like MathType and Microsoft Equation Editor (now bundled into Office 2010), but particularly the widespread, cult-like use of TeX and LaTeX, the gold-standard of typesetting systems, which has been adopted by academics, scientists (and more importantly, publishers) since its development in the late 1970’s. As you may have experienced, the divide between those who are willing to publish some math (that may not look perfect but was generated with little effort), and those whose mathematical expressions must look nothing-less-than-perfect (no matter the effort), is enormous; the first camp prefers limited (but easy-to-use) equation editors, whereas the other favors TeX or LaTeX, and publish math online by rendering their documents into PDFs, in a way avoiding the web altogether.

So, in order to do the right thing we all should learn MathML, right? Wrong. The same way that most of us who publish web content on a regular basis (through blogs, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) do not type HTML code from scratch, there are many ways to generate MathML code from other sources. Here’s a nice list of software tools that will allow you to render (or convert) your math expressions into MathML. Just keep in mind that, in order to be able to display MathML code natively (i.e. without a special plug-in), you must use a good web browser (i.e. one that cares about open standards). Until recently, everybody’s favorite Firefox was the only browser that supported MathML natively, but since August, 2010, Safari and Google Chrome also do. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, Internet Explorer does not support MathML natively -only through the third-party plug-in MathPlayer.)

Now, how can we generate beautiful math expressions in WordPress sites— like this one? Sure, you could reconfigure your WordPress server by hacking into the the PHP, but there are easier ways. Since WordPress is an open-source application, developers are continuously creating new functionality for it: here’s the latest list of all LaTeX plugins for WordPress. We’ve only tried a few of these, but the main difference between them is the fact that most generate math expressions as graphics (GIFs or PNGs), whereas only a few of them generate proper MathML code. (Also, in some cases, the code compilation and rendering of images occurs locally, whereas in other cases, it happens remotely, which is a relevant point to discuss with your systems administrator.)

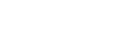

Here at Vassar, we have just installed the QuickLaTeX plug-in and are very happy with its performance— if what you want to do is typing or copy/pasting your good ‘ol LaTeX commands. All you need to do is to start your post with the expression “latexpage” (between square brackets), and then enter your LaTeX code below.

Here’s an example:

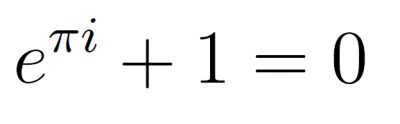

This is a really famous equation:

(1)

If you would like to include inline equations, you can just type them between ‘$’ signs, like this:

.

If you want to number only some of your equations, use the displaymath command instead of the equation command to skip those that should go un-numbered, like this one:

Here are two nice, more sophisticated equations featuring an infinite sum and an indefinite integral:

(2)

(3)

As you can see, the equations are rendered as PNG image files (sure, it’s not MathML, but it’s the next best thing.) Here’s the code that generates the expressions above:

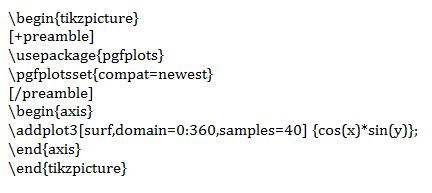

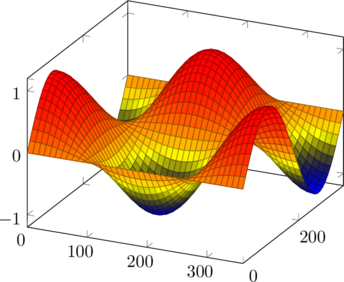

QuickLaTeX can also render graphics on the fly through the pgfplots package. Here’s an example:

Here’s the code that generated the 3-D plot above:

Here’s a quick start guide to QuickLaTeX, featuring some neat examples.

As you can see from the results above, this plugin is already available on our WordPress production system. Please let us know what you think!