By Luna Kang

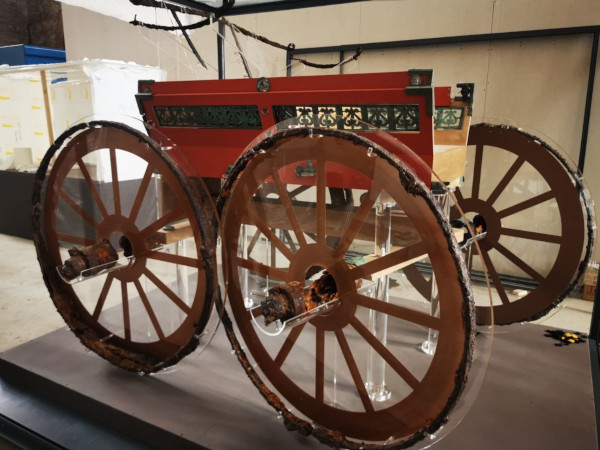

A stunning chariot was unearthed recently in Pompeii, Italy. Even though many archaeologists unearth all sorts of artifacts in Pompeii, this find was unique because of its exceptional condition and because archaeologists identified it as a pilentum. A pilentum was a ceremonial cart used to transport elite members of the community to ceremonies or parades. By restoring this chariot to its former beauty, archaeologists can understand more about the culture in Pompeii before the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

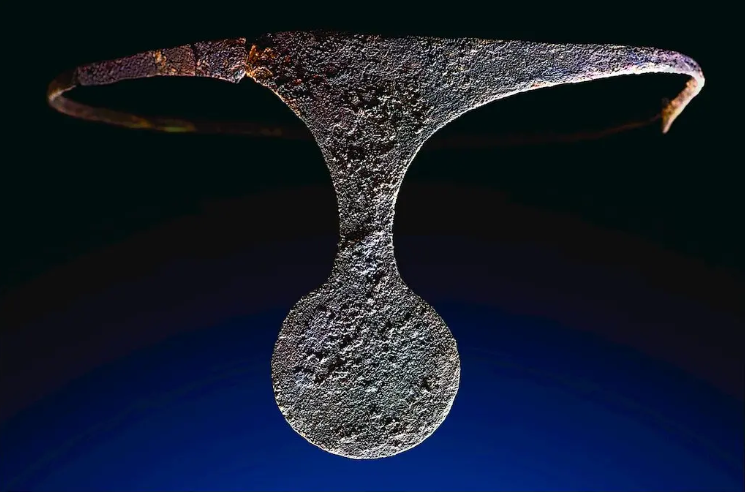

Roman chariots that are found are built from vastly different materials than today’s more modern transportation. Roman chariots were often made of wood for the body and seats and iron for the wheels. This specific chariot was also made with bronze ornaments covering the body’s outside. Each material used to build this chariot helps archaeologists put a date stamp on the artifact. For instance, the iron and bronze metals used are typical of Roman works, such as their armor, weapons, chariots, and boats. By observing what the artifact is made from, archaeologists can place it along a timetable of Earth’s history.

Archaeologists found the chariot on January 7th, 2023. A small iron artifact caused the archaeologists to believe something bigger was buried beneath them. After excavating for weeks, the team unearthed a big chariot. This splendid chariot, now identified as a pilentum, wasn’t used for gardening, carrying trash, or running errands. This four-wheel processional chariot was reserved for parades and processions or for bringing the lucky bride to her new home. The chariot, which was recently on display at Pompeii for the first time in 2023, was located almost entirely intact in a portico connected to the horse stables at an ancient villa near the walls of the city. A layer of cinerite had protected the high iron wheels, the arms and backrest, and the elegant decorations along both sides of the chassis.

According to Massimo Osanna, Director General of Italian Museums, “When the chariot was discovered during the excavation, it was of exceptional importance due to the information it offered about this form of transport – a ceremonial vehicle – which has no parallel in Italy. . . . This is the first time that a pilentum has ever been reconstructed and carefully studied.” Because of this discovery, made possible by the destructive force of Mt. Vesuvius’s ash, we can understand more about the hierarchy of Roman civilization.

Further Research:

The History of Pompeii

The Full Reconstruction

Reference List:

http://pompeiisites.org/en/comunicati/reconstruction-of-the-ceremonial-chariot-from-civita-giuliana/

https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-rome/pompeii

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/volcanic-ash/