By: Hudson Double

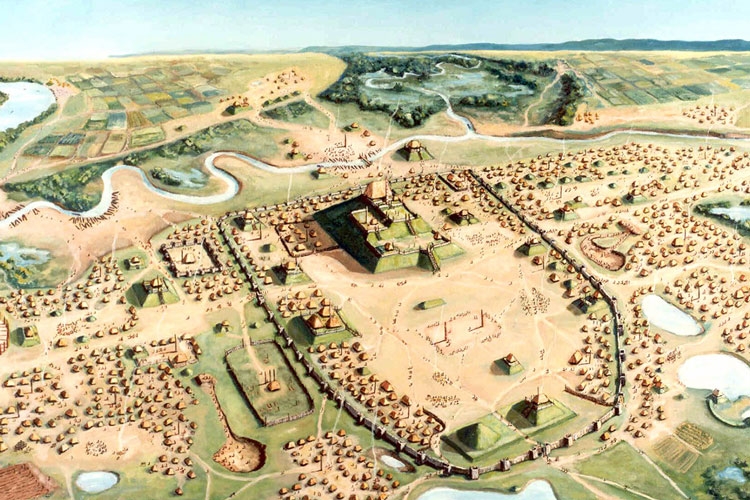

Fig 1: Cahokian Mounds Photographed by Ko Hon Chiu Vincent

Nearly 1000 years ago a new city was founded and would eventually grow to a size of between 10-20,000 people over the coming years (Pauketat 2009). This great city, known as Cahokia, was not in Europe, but sat on the banks of the Mississippi, just a few miles away from what has since become St. Louis. Around the year 1050 CE, the city quickly expanded, growing into the largest city ever in North America up to that point in time, but just a few hundred years later, from 1250-1350 CE, the city would quickly unravel (Pauketat 2009: 138). Though there are multiple theories behind the collapse of Cahokia, through this post I intend to examine the idea of climate change acting as the catalyst for the collapse of the city.

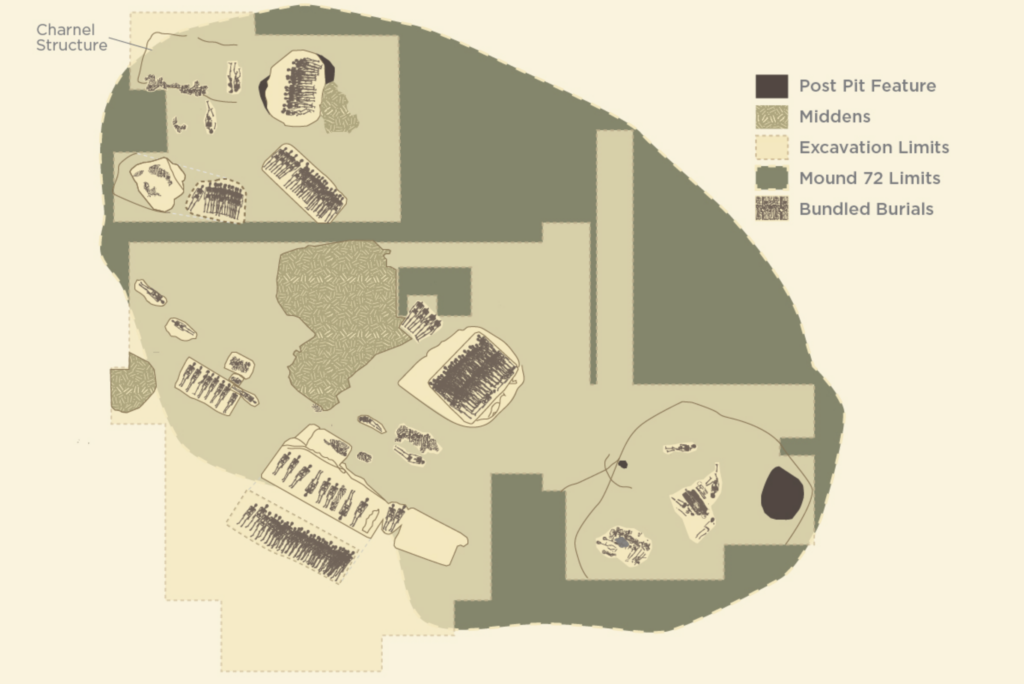

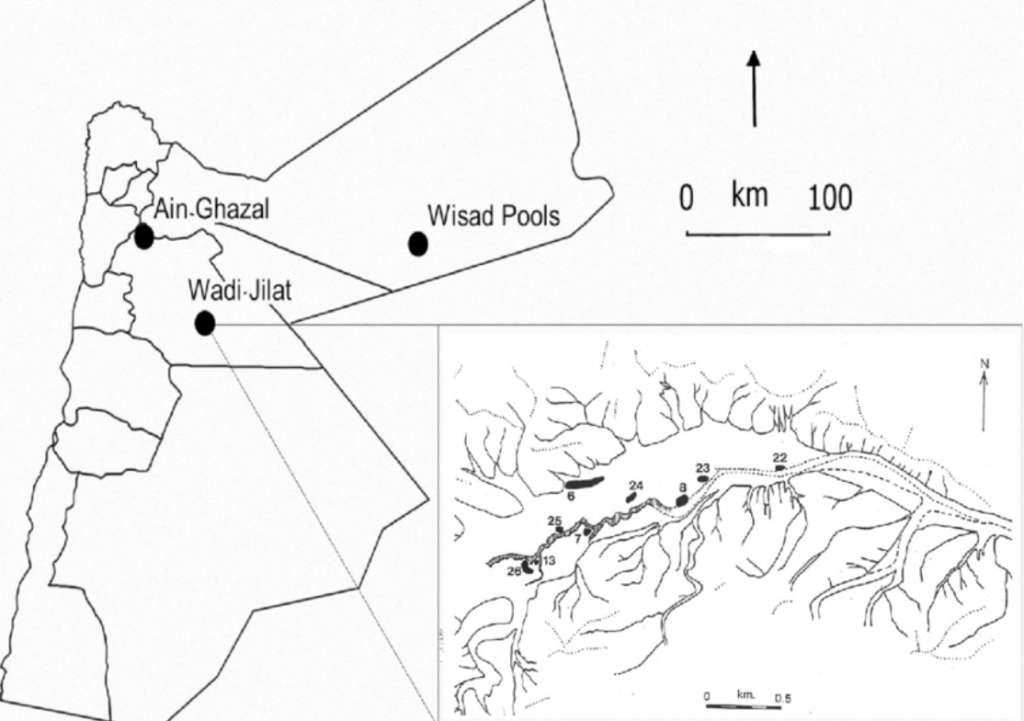

Fig 2: Settlements Around Cahokia

To begin, this theory which has been discussed in the media repeatedly over the past few years essentially states that Cahokia both formed and collapsed as a result of environmental factors. Starting with the methodological approach, the primary way by which climate records on the region were gathered was by collecting samples of mud from the bed of lake Martin. By examining the calcium carbonate crystals between the stratigraphic layers, they were able to create an accurate record of rainfall over specific periods of time. These records showed that there was increased rainfall starting about 100 years before the foundation of the city in 900 CE (Chen 2017). Increased temperatures and rainfall as a result of the Medieval Climatic Anomaly—also known as the Medieval Warm Period—resulted in increased fertility, allowing for corn to thrive. As a result, isotopes found in corn began being found in the Skeletons of Mississippian skeletons within decades, and continued through until the foundation of the city (Chen 2017).

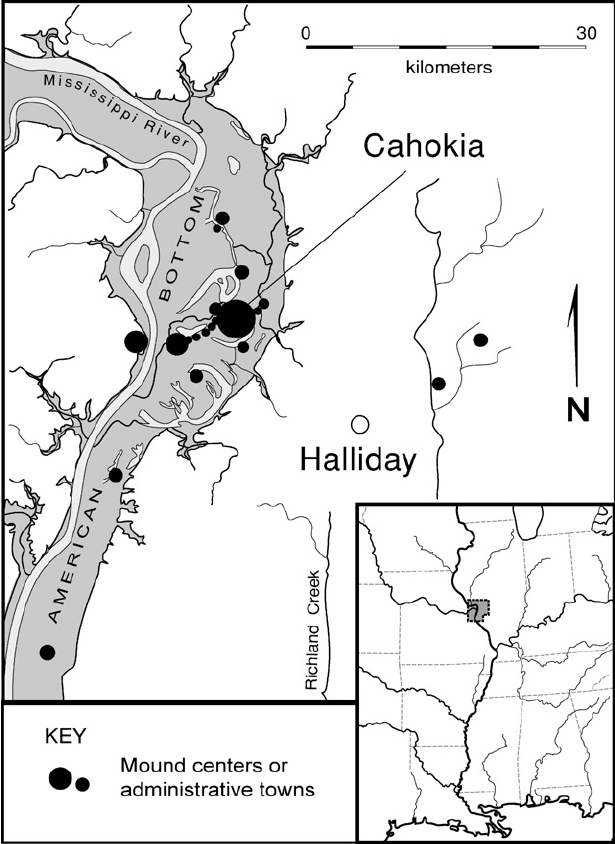

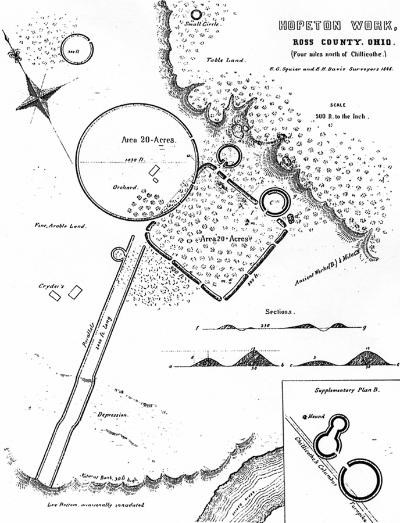

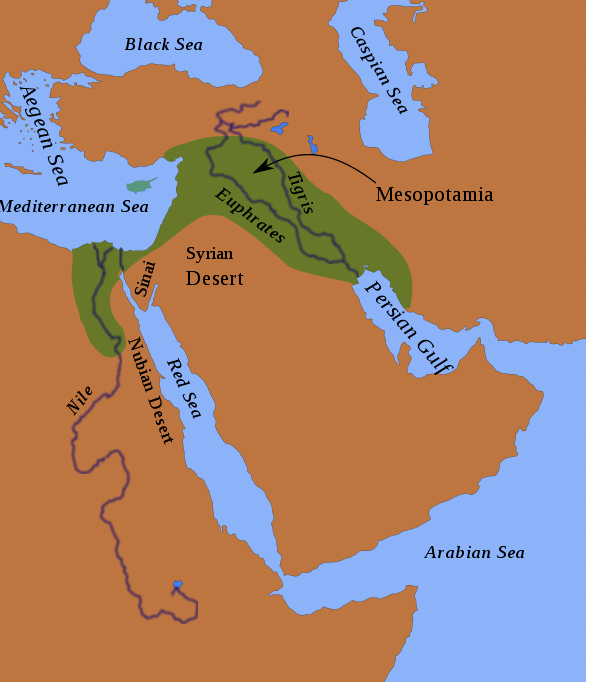

Fig 3: The Famous Monks Mound and Central Plaza

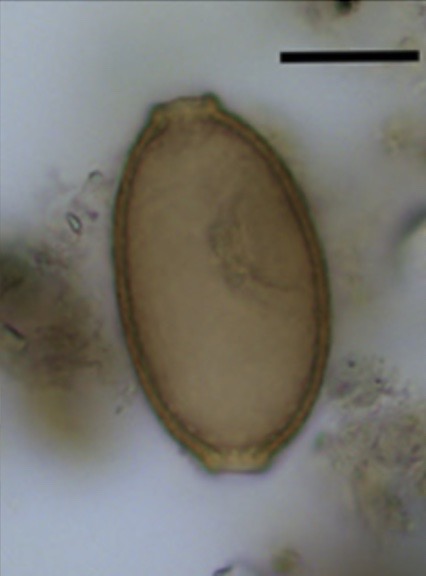

Following the foundation of the city, the climate remained fairly active and fertile for the following centuries, before rapidly cooling around the year 1200 CE (Chen 2017). Furthermore, starting around the year 1150 CE there had been a series of droughts which had seriously impacted the farming potential of Cahokia, and continued through the following centuries as the climate cooled (Benson 2009: 467). Evidence coming from analyzing fecal particles in Horseshoe lake, just north of Cahokia, lends further evidence for the idea the city may have been struggling to effectively produce food, leading to an exodus of people before 1350 CE (White 2019). Overall, though there is no way to know for sure what caused the collapse of Cahokian civilization, there is considerable evidence lending credence to the idea of climate factors ushering in the end of the civilization. While there are several other environmental theories, mainly surrounding overharvesting of resources, the evidence provided by the analysis of particles in nearby lakes and more provides profound insight into the events that took place in the great city of Cahokia.

References

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. (2019, February 25). Climate change contributed to fall of Cahokia. ScienceDaily. Retrieved November 23, 2023 from link

- Vincent, Ko Hon Chiu. “Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.” Cahokia Gallery – UNESCO World Heritage Centre, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Gallery. Accessed 24 Nov. 2023.

- “Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley”: The Mounds of Native North America – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: Link [accessed 24 Nov, 2023]

- Benson, L. V., Pauketat, T. R., & Cook, E. R. (2009). Cahokia’s Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change. American Antiquity, 74(3), 467-483.

- Everding, Gerry. “Women Shaped Cuisine, Culture of Ancient Cahokia – the Source – Washington University in St. Louis.” The Source, Washington University St.Louis, 13 Nov. 2020, Source

- Shukla, Priya. “Human Poop Reveals That Climate Change Caused the Fall of Cahokia, a Medieval Native American City.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 12 Apr. 2019, Forbes

- White, A.J., and Lora R Stevens. “Fecal Stanols Show Simultaneous Flooding and Seasonal Precipitation Change Correlate with Cahokia’s Population Decline.” PNAS, Northwestern University, Feb. 2019, link

- Chen, Angus. “1,000 Years Ago, Corn Made This Society Big. Then, a Changing Climate Destroyed It.” NPR, NPR, 10 Feb. 2017, NPR

Image References

- Fig 1: Vincent, Ko Hon Chiu. “Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.” Cahokia Gallery – UNESCO World Heritage Centre, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/198/gallery/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2023.

- Fig 2: Benson, L. V., Pauketat, T. R., & Cook, E. R. (2009). Cahokia’s Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change. American Antiquity, 74(3), 467-483.

- Fig 3: “Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley”: The Mounds of Native North America – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Photograph-of-the-central-precinct-of-cahokia-The-100-foottall-monks-mound-is-visible_fig5_322040930 [accessed 24 Nov, 2023]