Throughout history, jewelry and other decorative items have been unquestionably important symbols of culture, whether it be to showcase wealth, social status, or religious affiliation. For years, archaeologists have discovered jewelry dating back to the pre-Columbian era of North America, noting a few prominent materials: stone, shell, bone, and clay. Cahokia, as well as other Native American societies, commonly manufactured mass amounts of beads from such materials, giving archaeologists a glimpse into everyday productivity within pre-Columbian civilizations in North America.

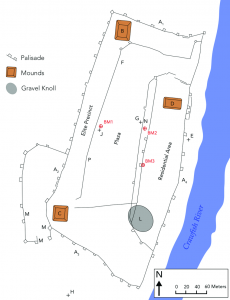

The city of Cahokia’s peak influence occurred roughly around 1100 AD, and it is characterized as the largest city Pre-columbian city in North America. Not only is it deemed so influential because of its sheer size, but largely due to its vast cultural outreach as well (Thomas and Perkins 2016). Upon the discovery and excavation of the Cahokian mounds, archaeologists discovered a number of burials, some of which were surrounded by thousands of shell beads (Figure 1). One bead material, in particular, lightning whelk shells, are thought to have symbolized many significant ideas in Cahokian culture. Due to their unique spiral shape, lightning whelk shells are thought to have symbolized the cycles of life and death, as well as served as a symbol of wealth, seeing as they were harder to obtain (Kozuch 2021). In addition to the symbolic importance of the shells, even their general quantitative discovery proved important to archeologists because it meant there was some form of a mass manufacturing system in Cahokia. While this argument is, for the most part, widely accepted, whether or not the beads were the result of specialized full-time labor or part-time domestic activities is still up for debate (Kozuch 2021).

Figure 1: Marine shell beads discovered in the mounds of Cahokia. Retrieved from Illinois State Museum.

While Cahokian beaded jewelry mainly consisted of marine shell materials, others utilized stone and bone materials due to their more inland geography. Originally found in what is now Illinois, archaeologists discovered Mississippian-era stone beads, made from grinding and drilling rock with stone tools until the bead reaches its desired shape (Illinois State Museum 2000). Similarly to the manufacturing process of stone, necklaces made from hollowed bird bones were discovered at the Spiro Mounds located in Eastern Oklahoma. The specific necklace depicted below was a total of 34 inches in length and is estimated to be from between 900 A.D. and 1450 A.D. (Sanderson 2021). While many aspects of American culture have changed following the Mississippian Era, it is clear that the decorative and adorning qualities of jewelry have remained entirely relevant throughout society today.

Figure 2: Necklace made from hollowed bird bone discovered at the Spiro Mounds in Eastern Oklahoma. Retrieved from Museum of Native American History.

Bibliography:

Kozuch, Laura. 2021. “Cahokia’s Mound 72 Shell Artifacts.” Southeastern Archaeology 40 (no.1): 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578x.2021.1873057. Accessed 21 November 2022.

“Mississippian Economy Clothing.” Illinois State Museum, 2000. https://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/pre/htmls/m_clothing.html.

Sanderson, Jazlyn. 28 January 2021. “Spiro Mounds Bone Bead Necklace.” Museum of Native American History. https://www.monah.org/artifact-blog/2020/10/31/spiro-mounds-bone-bead-necklace. Accessed 21 November 2022.

Thomas, Jonathan, and Tyler Perkins. 19 April 2016. “Shell Bead Production at Cahokia.” the Digital Archaeological Record https://core.tdar.org/document/404597/shell-bead-production-at-cahokia. Accessed 21 November 2022.

Additional Resources: