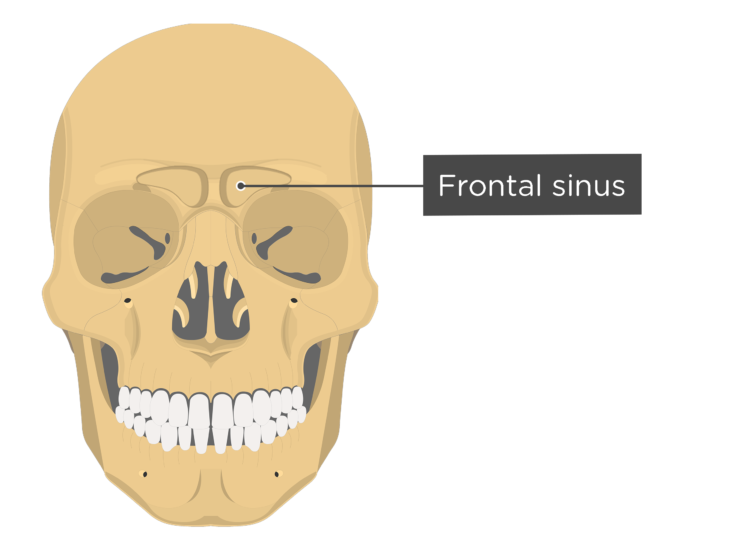

A new study conducted by Chris Stringer and colleagues have led to a fascinating possibility that variation in the size and shape of the frontal sinuses can be linked to the development of the frontal lobe; the part of the brain accountable for emotion, planning, and speech. Frontal sinuses are “cavities inside the frontal bone located at the junction between the face and the cranial vault and close to the brain” (Balzeau, 2022). Yet, despite knowing the job and role of the frontal sinuses, there is still very little knowledge on the evolutionary aspect of it.

Located right above the nose, the frontal sinus which has often been forgotten historically now offer possible insight to past relationships with ancient hominids.

As mentioned, Stringer and his team were able to undergo multiple studies to link the size of the frontal sinus among previous fossil hominids with the frontal lobe. First off, they conduced CT scans on 94 individuals, which were from more than 20 species of human fossil hominids. From this, they created 3D models of their frontal sinuses and compared them with one another. Their length and widths, as well as their shapes were recorded which led to further observations. For example, the team were able to determine that “species such as Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens have distinct ranges of sinus size, which researchers suggest could be linked to evolutionary constraints caused by the development of characteristics such as larger brains” (Bartek, 2022). This shows the evolutionary aspect of the human, emphasizing in the different amount of space the brain had to grow for each species. A common denominator that was found among the 3D models was the sinuses and the size of the frontal lobe starting from homo erectus and onwards. The size of the sinuses proved to be persistent and correlate with the development of one of the brain’s lobes (short extension) compared to the other. Studies suggest this part of the brain plays a role in determining humans dominant hand and is shared amongst most humans today.

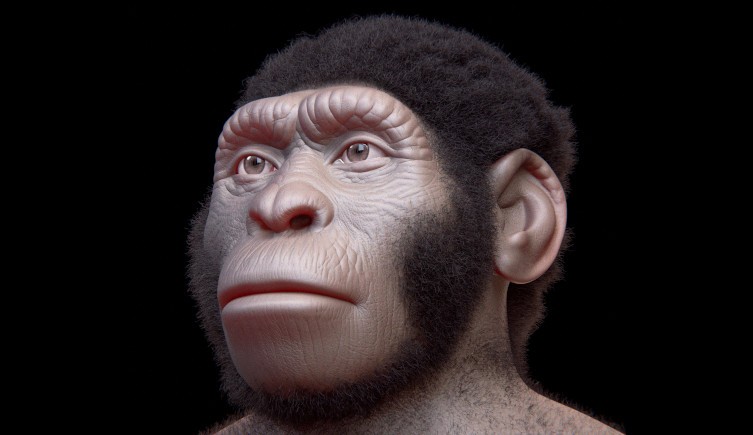

However, as much discovery that was made, there were also many unanswered questions and confusion amongst the group. Homo rhodesiensis, for instance, display a very unusual large sinus size compared to their relatives. Although there is no clear explanation for their large sinus size, the team hypothesized that they are a specialized group. This means that their way of living and the environment they were exposed to was different from their relatives.

These species have extremely large brow ridges, which leads many to hypothesize their role in social signaling.

Although these new studies provided new insight and discoveries towards our human past and evolutionary progress, more studies will have to be done to answer questions like these. Sinuses should be evaluated and looked more upon for future studies conducted, as they will help us understand how todays human species came to be.

Further Readings:

Clues to Apes and Human Evolution

To understand human evolution, follow the trail of sinuses

References:

Saraceni, Jessica, 2022. “Frontal Sinuses in Hominin Skulls May Offer Clues to Evolution.” Archeology. https://www.archaeology.org/news

Balzeau, Antoine, 2022. “Frontal sinuses and human evolution.” Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abp9767