The flat ontology of the Neolithic society of Çatalhöyük gives us insight into the value of post-humanism as an archeological approach. Flat ontologies and post-humanism are interconnected frameworks that renounce anthropocentrism (Harris and Cipolla 2009). Flat ontologies reject the ranking of different beings, believing them to be all of equal importance. Post-humanism believes that we are not in opposition to nature and non-human animals. Instead, we must understand ourselves in relation to other animals and plants and understand them as beings of agency. While processualists are interested in the economic benefits of animals, post-processualism looks at the dynamic relationship between beings. Donna Haraway believes that we become humans with, rather than against, animals. Archeologists are beginning to grant plants and animals a different role in the past (Harris and Cipolla 2009, 169). Approaching archeology by looking for flat ontologies and applying post-humanist theory can help us gain a broader understanding of joint plant, animal, and human communities.

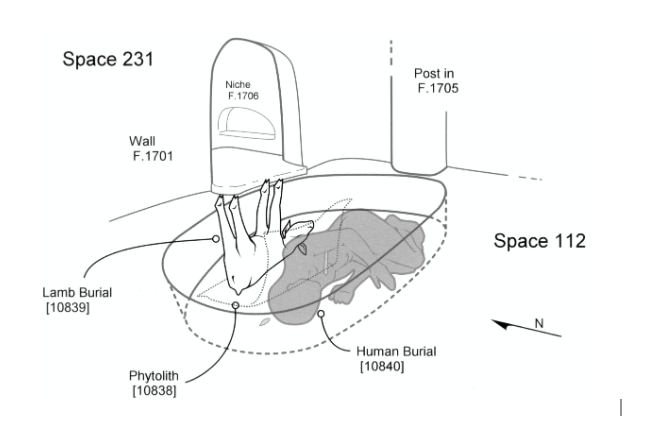

Çatalhöyük’s burial grounds indicate that they were deeply interrelated with sheep. Çatalhöyük buried their dead in graves under their houses. When excavating, archeologists found a grave with a man and a lamb buried side by side in lot one-hundred and twelve on the North platform (Russel and Düring 2006). We know this burial was not a sacrifice because in Çatalhöyük, sacrificed animals did not have the same burial practices as humans and were never buried beside them. The burial of the lamb was very deliberate and indicates it had quasi-human status (figure 2). The lamb was placed on organic remnants believed to be a mat with their feet in the air. Burying the lamb in this position means their legs would have had to be held the entire time the soil was added. In Çatalhöyük, burial sites were often disturbed to bury more bodies. However, this grave was never disturbed. Sheep were not necessarily domesticated like other animals, and archeologists believed the man was a shepherd with a close relationship with the lamb. The crane dance and the burial at Çatalhöyük illustrate a dynamic relationship of reverence and respect for animals that challenges anthropocentrism.

Çatalhöyük’s burial grounds indicate that they were deeply interrelated with sheep. Çatalhöyük buried their dead in graves under their houses. When excavating, archeologists found a grave with a man and a lamb buried side by side in space one-hundred and twelve on the North platform (Russell and Düring 2006). We know this burial was not a sacrifice because in Çatalhöyük, sacrificed animals did not have the same burial practices as humans and were never buried beside them. The burial of the lamb was very deliberate and indicates it had quasi-human status (figure 2). The lamb was placed on organic remnants believed to be a mat with their feet in the air. Burying the lamb in this position means their legs would have had to be held the entire time the soil was added. In Çatalhöyük, burial sites were often disturbed to bury more bodies. However, this grave was never disturbed. Sheep were not necessarily domesticated like other animals, and archeologists believed the man was a shepherd with a close relationship with the lamb. The crane dance and the burial at Çatalhöyük illustrate a dynamic relationship of reverence and respect for animals that challenges anthropocentrism.

Further reading:

https://academic.oup.com/florida-scholarship-online/book/31462/chapter-abstract/289648496?redirectedFrom=fulltexthttps://www.catalhoyuk.com/archive_reports/2004/ar04_17.html

References:

Ferrando, Francesca. 2016. “Humans Have Always Been Posthuman: A Spiritual Genealogy of Posthumanism.” In Springer eBooks, 243–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5_15.

Gargett, Katrina. 2017. “Was There a Belief in the Mother Goddess at Çatalhöyük?” Çatalhöyük Research Project. September 13, 2017. https://www.catalhoyuk.com/node/736.

Harris, and Cipolla. 2007. “Multi-Species Archeology.” 2007.

Russell, Nerissa, and Bleda S. Düring. 2006. “Worthy Is the Lamb : A Double Burial at Neolithic Çatalhöyük (Turkey).” Paléorient 32 (1): 73–84. https://doi.org/10.3406/paleo.2006.5171.

Russell, Nerissa, and Kevin J. McGowan. 2003. “Dance of the Cranes: Crane Symbolism at Çatalhöyük and Beyond.” Antiquity 77 (297): 445–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003598x00092516.