After World War Ⅱ, the number of border walls all over the world increases significantly. Nowadays the border situation between the US and Mexico is widely discussed, and a wall is actually in people’s envision. What are some border walls in other countries like? Do they all function as the prevention of illegal migrants and refugees?

Serving similar purpose with the wall between US and Mexico, the security at Calais port between France and UK prevents illegal migrants from entering the UK. The security is equipped with detection technologies, such as heartbeat and carbon dioxide detectors, and both countries funded together for a “control and command center”. One difference between Calais port and US border wall is that Calais port prevents the migration problem “at source”, with the aid of strict systems, while the US border wall exposes migrants into the potential danger in the desert. What’s more, between UK and France governments, there is a promoted joint agreement to determine if the migrants are accepted as asylum seekers, get detained or deported.

Another example is the fences in Europe. Hungary and Slovenia are two countries with the region’s largest expanse of fences. These border fences serve to prevent illegal migrants as well but face more religious issues than the one between US and Mexico. It is revealed that people living near these barriers often find that they serve little purpose and can be psychologically damaging. For example, children in the camp in village are scared of their proximity to the fence.

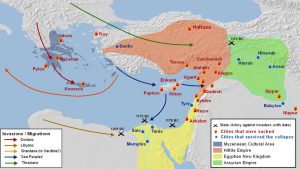

We are probably familiar with US president Trump’s use of the Great Wall in China as a comparison to his plans of building the wall. However, these two walls actually serve distinct purposes. The Great Wall was built to prevent exterior military incursion instead of as a security barrier. The construction of Great Wall started in 7th century BC, went through several dynasties, and finished in Ming dynasty. The Great Wall is not impregnable in Chinese history, so perhaps the border wall between US and Mexico will not be totally impregnable as well; moreover, according to Edward Alden, trade policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, increased enforcement efforts along the border may explain about 35 to 40 percent of the decline in illegal immigration flow.

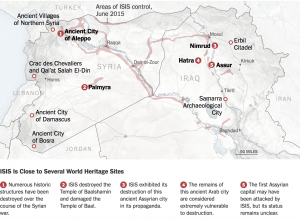

Nowadays, the border wall that is actually similar to the Great Wall is probably the wall built by Saudi Arabia. The 600-mile-long wall in their northern frontier is built to prevent ISIS from attacking the oil-rich territory.

If the government is determined to use border wall to prevent migration, it might be better to set up an excellent system instead of exposing the migrants in danger in the desert. And even though the wall may serve well politically, we need to think about how to reduce the psychological effect it brings to people who live nearby.

References:

Hjelmgaard, Kim

2018 From 7 to 77: There’s been an explosion in building border walls since World War II. Electronic document,

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/05/24/border-walls-berlin-wall-donald-trump-wall/553250002/, accessed December 2, 2018

BBC News

2016 Calais migrants: How is the UK-France border policed? Electronic document,

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33267137, accessed December 2, 2018

Hjelmgaard, Kim

2018 Trump isn’t the only one who wants to build a wall. These European nations already did. Electronic document,

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/05/24/donald-trump-europe-border-walls-migrants/532572002/, accessed December 2, 2018

Michelle Ye Hee Lee

2016 Why Trump’s comparison of his wall to the Great Wall of China makes no sense. Electronic document,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2016/03/08/why-trumps-comparison-of-his-wall-to-the-great-wall-of-china-makes-no-sense/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.972ab6dde511, accessed December 2, 2018

ShantiUniverse

2015 Saudi Arabia Builds 600 Mile Wall to Keep Islamic State OUT! Electronic document,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AG_m4LKOCBk, accessed December 2, 2018

Further Reading:

The (Anthropological) Truth about Walls

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/the-anthropological-truth-about-walls/

The Trump Wall in Archaeological Perspective

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2016/11/14/the-trump-wall-in-archaeological-perspective/

Images: