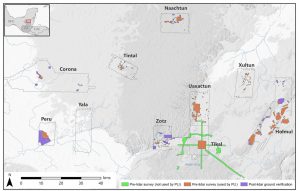

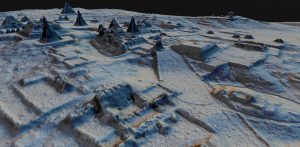

For years, archaeologists have been using LIDAR to study ancient Maya sites. Recently, an analysis was released of a 2016 survey of the Maya lowlands. The survey, the largest ever done in the region, covered 2,144 square kilometers of land and uncovered a total of 61,480 ancient man-made structures (Canuto et. al 2018). Although the population density was clearly not homogenous – some areas were very rural while others were were far more urban – the researchers estimate an average population density of about 120 people per square kilometer, or about 7 to 11 million people total (Canuto et. al 2018). According to Dr. Thomas Garrison, one of the archaeologists involved with analyzing the data, this discovery is revolutionary because it places population estimates in this region at several times more than was previously thought and reveals new information about the politics, economics, and agricultural practices of the area (St. Fleur 2018).

As one might expect, a significant amount of farmland was needed to produce food for such a large population, and this could be found right there in the lowlands (Canuto et. al 2018). According to archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli, “All of these hundreds of square kilometers of what we thought were unusable swamp were actually some of the most productive farmland” (St. Fleur 2018). The urban areas would have relied on the rural ones for importing food, since the LIDAR scans show that there was not enough farmland immediately surrounding most of them to support their populations. In fact, the many kilometers of roadways imply a high level of interconnectedness between much of the surveyed area, while the infrastructure layout and connectivity more generally reveals that there was likely large-scale planning done by a centralized power (Canuto et. al 2018).

This LIDAR survey reveals important information about the farming practices of the Maya as well as about the extensive infrastructure and organization of their societies. The intensive farming itself is not an isolated thing, since it is known that Mayan agricultural practices and urban expansion had significant impacts on the land (Stromberg 2012). But what is surprising is the location and extent of the land modification. This study will help archaeologists and historians better understand the Maya lowlands, and develop a better image of what their societies look like, and possibly even why they fell. Since our modern societies are facing increasing environmental crises (also partially from unsustainable farming practices) it is more important than ever to learn from the past to change the future.

Works Cited:

Canuto, Marcello et al.

2018 Ancient Maya Lowland Complexity as Revealed by Airborne Laser Scanning of Northern Guatemala. Science Magazine, accessed 1 November 2018.

St. Fleur, Nicholas.

2018 Hidden Kingdoms of the Ancient Maya Revealed in a 3D Laser Map. The New York Times, accessed 1 November 2018.

Stromberg, Joseph.

2012 Why did the Mayan Civilization Collapse? A New Study Points to Deforestation and Climate Change. Smithsonian Magazine, accessed 3 November 2018.

Image Sources:

Estrada-Belli, Francisco.

2018 The New York Times, September 27, 2018, https://static01.nyt.com/images/2018/10/02/science/28TB-MAYA/28TB-MAYA-jumbo-v2.jpg?quality=90&auto=webp , accessed 3 November 2018.

Canuto, Marcello et. al

2018 Science Magazine, September 2018, http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/361/6409/eaau0137/F4.large.jpg , accessed 3 November 2018.

Further Reading:

“Drought and the Ancient Maya Civilization.” https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/abrupt-climate-change/Drought%20and%20the%20Ancient%20Maya%20Civilization

“Mayans Converted Wetland to Farmland.” https://www.nature.com/news/2010/101105/full/news.2010.587.html