Studying human remains reveals unique information to archaeologists about a civilization’s customs and traditions. In addition to cause of death, archaeologists can create a complete profile of the body’s lifestyle based on physiological features combined with intense critical thinking. Similarly, the remains of animals in the area can also provide great insight into a society’s culture by helping archaeologists gain a better understanding of the type of environment that the people lived in. What kind of predators threatened their safety? Did they domesticate animals and train them to perform actions to benefit the entire community? A group of archaeologists used animal remains to analyze a unique aspect of Mayan culture—the interaction between different social and economic classes based on the distribution of animal resources.

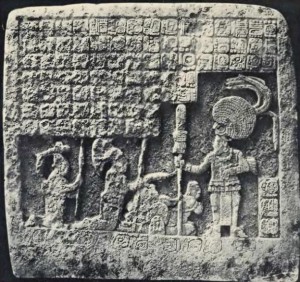

This stone-carved depiction of a social-elite seizing resources from a lower class member of Mayan society serves as one of the few examples of art depicting social-class division.

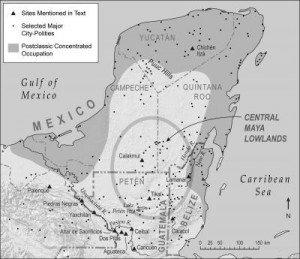

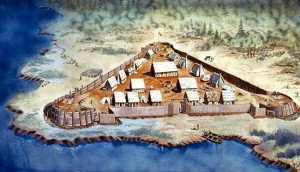

Very little was known about the political and economic systems of Mayan society, as compared to archaeologists’ extensive knowledge of their advances in art and astronomy. The way animal resources were distributed offered clues to the ways in which different social classes interacted, and archaeologists learned that their societies were not homogeneous by any means. Instead, there were complicated systems in place to regulate trade relations, food distribution, and accessibility to species. Because animals were used so widely for hides, tools, jewelry, and musical instruments, studying the geographic distribution of these resources revealed that there were elite classes that controlled a majority of the valuable resources. But surprisingly, the middle classes used the widest variety of animals, as the wealthiest people only used exotic animals, such as jaguars and crocodiles, and the poorest could only afford to use inexpensive animals, such as a variety of fish and shellfish.

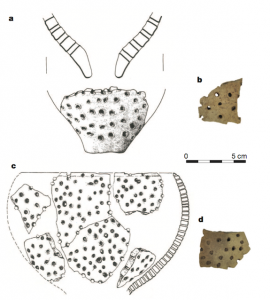

These animal bones, teeth and a cut jaw bone from a tapir, are an example of the ways Mayans used animal bones to create tools and instruments for daily use in society.

The study of animal bones has provided insight into the way Mayan cities interacted with surrounding villages through trade and commerce and has provided such extensive information because Mayan culture relies so heavily upon animal resources accomplish. I am amazed by the amount of information that the archaeologists were able to infer about human cultures and tendencies from the examination of seemingly-unrelated artifacts. Similar observations and critical thinking are applied when analyzing human remains as when uncovering truths about a society and their culture. In the case of the Mayan civilization, the discovery of specific animal remains led archaeologists to believe that there were stricter class boundaries than previously thought. The emergence of social hierarchy is an aspect of the “big picture” of Mayan civilization and social structure. Without the creative approach to this investigative archaeology, they would be missing evidence of a significant aspect of Mayan culture which serves as further evidence of the often-overlooked sophistication of the ancient American civilizations.

Further Reading

http://phys.org/news/2015-10-temples-ancient-bones-reveal-mayan.html

http://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/animal-bones-shed-light-lifestyle-citizens-ancient-maya-cities-004405

http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2015/article/beyond-the-temples-ancient-bones-reveal-the-lives-of-the-mayan-working-class

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/researchers-analyse-animal-bones-understand-how-working-class-mayan-civilisation-lived-1526449