Central Park is one of the most iconic attractions in New York City. It spans over 51 blocks and boasts 843 acres of lawns, ponds, and public walkways. It is easy to believe that Central Park has always been a part of the city, but before 1857, several well-established minority communities existed where the park stands today.

On July 21, 1853, the New York State Legislature enacted a law that designated 750 acres of land to the creation of a public park. The official history of Central Park, provided by the Central Park Conservancy (CPC), states that “socially conscious reformers” created central park with the intent to “improve public health and contribute greatly to the formation of a civil society.” There is no mention of the businesses destroyed, the churches and schools demolished, the families that were evicted. Most public records fail to recognize how Central Park conveniently destroyed many lower income “shanties” inhabited by “land squatters” and the less desirable residents of the city.

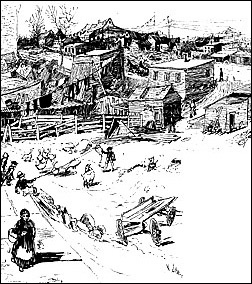

Seneca Village was one, if not the first established African American communities in NewYork City. It was established in 1825 as an all African American community and by 1857, the year of its destruction, it was 30% Irish-American. Despite their portrayal in the newspapers of the time, the residents of Seneca Village owned their property and usually paid taxes. The community had a total of three churches, three cemeteries, and two schools. Records show that over 589 people lived in Seneca Village in its thirty-two years of existence. On a webpage dedicated to the Seneca Village community, the CPC states that despite the fact that “many protests were filed in the New York State Supreme Court, as is often the case with eminent domain,” those living within the boundaries of the proposed park were “compensated for their property.” It tells nothing of how the public petitioned to save their community or the police force used to violently evict families from their homes. By 1857, according to the CPC, approximately 1,600 people, including all 264 Seneca Village residents were displaced from their homes.

Seneca Village is only one community destroyed in the creation of Central Park, and though it is well known now, it took nearly half a century to be found. City records often fail to acknowledge the violent eviction of places like Seneca Village and the difficulty former residents had in reforming the community. Today, many of the neighborhoods and people that existed before the park remain off public records and wait to be rediscovered.

Further reading:

http://www.npr.org/sections/theprotojournalist/2014/05/06/309727058/the-lost-village-in-new-york-city

http://www.mcah.columbia.edu/seneca_village/

http://projects.ilt.columbia.edu/seneca/start.html

References:

http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/seneca-village-site.html

http://www.centralparknyc.org/home/

http://www.nytimes.com/1997/01/31/arts/a-village-dies-a-park-is-born.html?pagewanted=all

Pictures found at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Village#/media/File:Seneca_Village-Central_Park-Nyc.gif

http://www.gothamgazette.com/graphics/cpsenecadrawing.jpg