Bands, the first classification of human social organization, consist of small groups of one hundred or less all related by blood or marriage. For the most part, hunter-gatherer groups live in these small societies. For most of our history as well, anthropologists suggest that all members of our species, Homo Sapiens, lived in bands.[1] We were not the only ones, though. All our ancestors and our evolutionary cousins, Homo Sapiens Neanderthalensis, lived in these family bands as well.

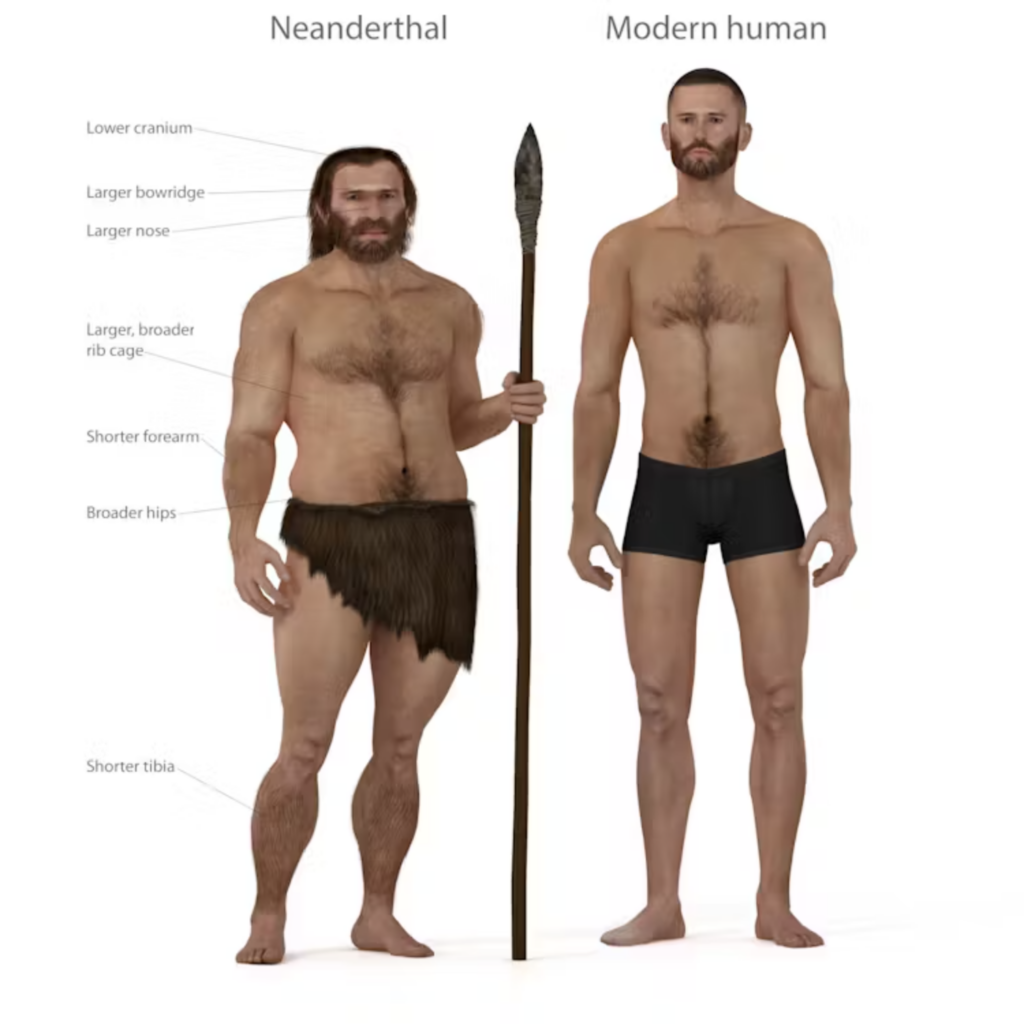

Neanderthals lived in Europe and West Asia starting 130,000 years ago and going extinct 40,000 years ago. They evolved from a European variant of the hominin Homo Heidelbergensis while our species evolved from the African variant. Neanderthals lived much like we did for most of our history, hunting game and foraging for plants. They looked very similar to us, save for a larger, longer skull, a shorter stature, a larger nose, and large eyes.

They were similarly intelligent to us and created sophisticated technology for both hunting and domestic uses.[2] They were spiritual people and some archaeologists suggest that they buried their dead.[3] We know they cared for their families, but until recently, we did not know how these families operated. From various genetic studies, anthropologists determined that Neanderthals lived in small groups of ten to twenty individuals.[4] Yet, a study published in October 2022 expanded on this information and gave us a greater understanding of Neanderthal family structures.

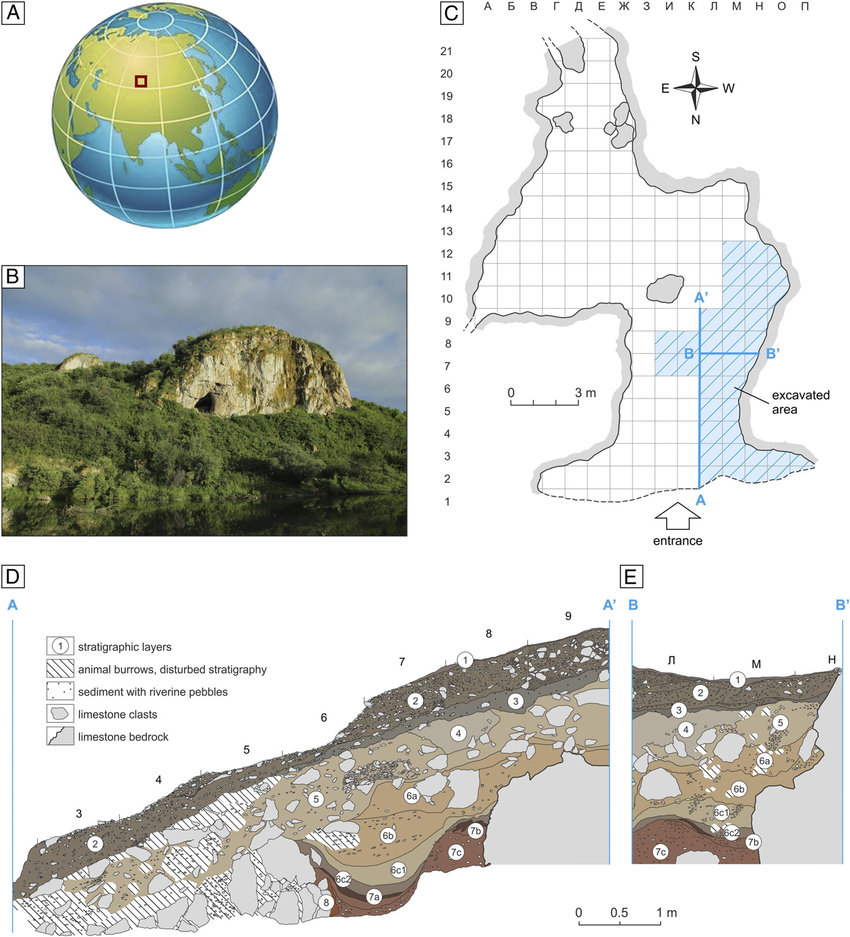

In Chagyrskaya Cave and Okladnikov Cave in Southern Siberia, hundreds of thousands of bones belonging to eighty individuals were found. All remains were of similar periods. The finding of this many individuals together is a massive discovery because if a community’s genomes are all studied in context with their relatives and neighbors, there will be greater insight into the community and lives of these people – not just their evolution.

The excavation and sequencing of bones in Chagyrskaya cave led to the discovery of the first Neanderthal father/daughter pair found. All other individuals sequenced from that cave were secondarily related as well save for two individuals. The study also looked into the roles of the sexes within Neanderthal society. DNA sequencing showed that the diversity of mitochondrial DNA was up to ten times greater than the diversity of Y chromosome DNA. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down from a mother to her children only, so this evidence suggests that the women of the species were more mobile than the men, moving around to other groups when they found mates.[5]

Genetic studies like this one from Chagyrskaya Cave can show an unknown side of behavior not yet seen before. Thrillingly, the excavation is not yet over. Only one-third of Chagyrskaya was excavated at the time of this study, and future discoveries only await further in the cave.

1. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/hunter-gatherer-culture/

2. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Neanderthal/Neanderthal-classification#ref339688

3.https://australian.museum/blog/amri-news/this-month-in-archaeology-did-neanderthals-bury-their-dead/