Cahokia was a major Precolombian city in modern-day Illinois near St. Louis, Missouri. It was the first major city in North America north of Mexico and stood for four centuries beginning in 950 CE – at its highest point, it reached a population of twenty to thirty thousand people in the year 1200 (Yates 2016). Despite being abandoned in the late twelfth century, Cahokia’s principal monuments–its mounds–still stand tall. The mounds were important to Cahokian religious and ritual life, and when their contents were unearthed, archaeologists found overwhelming evidence of human sacrifice.

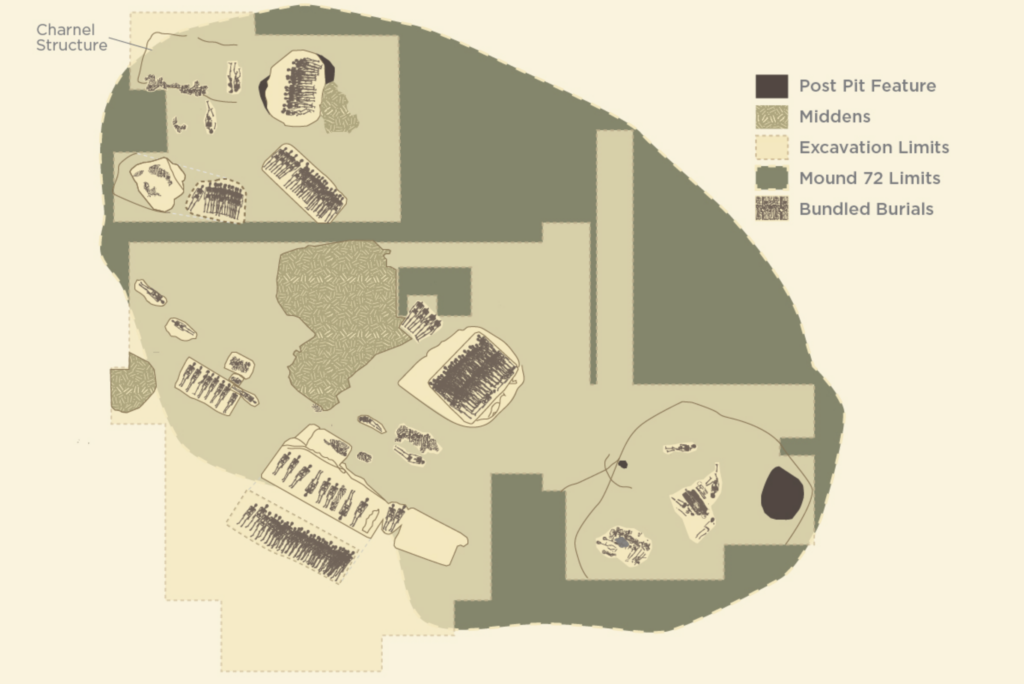

In Mound 72, archaeologists unearthed a mass grave of two hundred and seventy-two teenage girls and young women. The bodies of the women, for the most part, showed no signs of blunt-force trauma (Pauketat 2010). They were also not buried all at once–Pauketat estimates that based on how they were buried, at least one group of girls was sacrificed every generation, meaning there must have been something in their tradition that required a large number of young women to be sacrificed periodically. The age and state of the women suggest that their sacrifice was a ritual surrounding fertility (Isselhardt 2022).

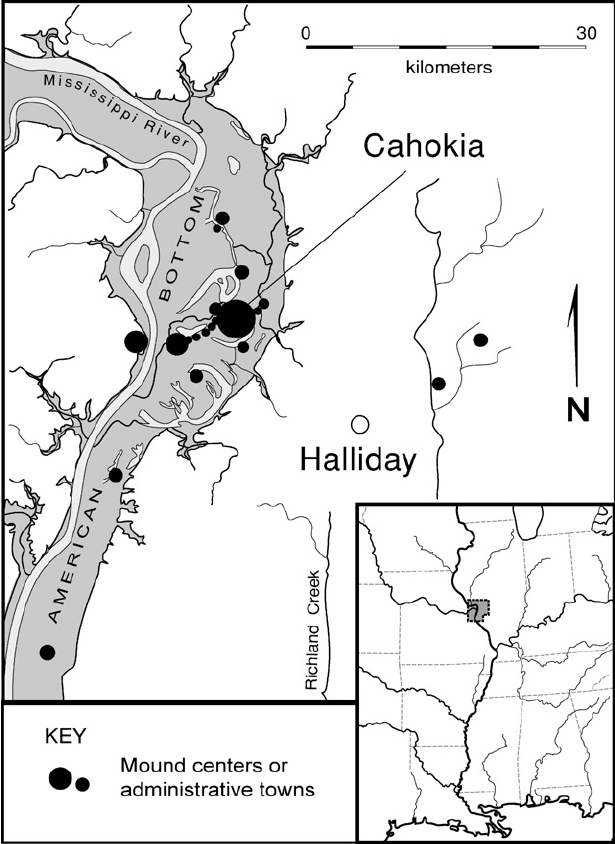

Pauketat suggests in his book Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on The Mississippi, that the sheer number of girls sacrificed in this ritual may have caused political unrest and points towards the excavation of the upland Halliday site with more feminine-oriented artifacts as a possible source for the young women used for these grand sacrifices. The hypothesis of this theory makes sense in the context of the book–a study on the teeth of the sacrificed women compared to the teeth of the human remains found in the Halliday site suggests that the Halliday citizens, much like some women who were sacrificed, had a diet high in maize and low in protein, meaning they were less healthy than inner-city Cahokians. (Pauketat 2010)

However, the idea that the sacrificed women were immigrants or non-locals has come into question. Using dental morphology, strontium isotope analyses, and dental metrics, a team of scientists was able to determine that the young women in the mass graves had a high degree of relatedness, for the most part, and came from the centralized Cahokia area. Strontium isotopes on the teeth confirmed that the crops they were eating were grown in the same regions as the crops eaten by the greater population of the city (Thompson 2015). This does not mean that Pauketat was entirely wrong, however. The group of women buried in one mound together called F229-lower had a slightly different morphology than the other women, especially in F229-higher, who showed a higher degree of relatedness with each other (Thompson 2015).

The investigation has raised more questions than provided answers. These would have been the daughters of the city and they would be at a large loss sacrificing so many young women. Only future research can tell us what we need to know about the sacrifice of the women at Mound 72.

Additional Information:

Strontium-isotope analysis: https://cais.uga.edu/service/strontium-isotope-analysis/#:~:text=Strontium%20isotopic%20ratios%20are%20widely,the%20decay%20of%2087Rb.

Dental Morphology:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128019665000068

Works Cited:

Isselhardt, Tiffany. “Girlhood and the Downfall of Cahokia.” Medium, February 27, 2022. https://historymuse.medium.com/girlhood-and-the-downfall-of-cahokia-4cc76290830f.

Pauketat, Timothy R. Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2010.

Pauketat, Timothy R. “Agency in a Postmold? Physicality and the Archaeology of Culture-Making.” Research Gate, September 2005. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226748570_Agency_in_a_Postmold_Physicality_and_the_Archaeology_of_Culture-Making.

Thompson, Andrew R. “New Dental and Isotope Evidence of Biological Distance and Place of Origin for Mass Burial Groups at Cahokia’s Mound 72.” Wiley Online Library, July 14, 2015. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.22791.

Yates, Diana. “Ancient Bones, Teeth, Tell Story of Strife at Cahokia.” ILLINOIS, August 4, 2016. https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/391703.