Archaeology deals with artifacts and human remains from the past. Forensic anthropology, specifically, is the “special sub-field of physical anthropology… that involves applying skeletal analysis and techniques in archaeology to solving criminal cases” (Smithsonian). While this may seem somewhat straight forward, there are ethical issues that are relevant when it comes to all forms of anthropology and archaeology, but forensic anthropology especially. It’s the “responsibility of all archaeologists to work for the long-term conservation and protection of the archaeological record by practicing and promoting stewardship of the archaeological record” (SAA, 2018). However, this is not always taken seriously as human remains are often dug up, examined, photographed, posted and shared physically and electronically, and in some cases more severe actions occur, such as taking remains to the moon.

Ethics in anthropology and archaeology are especially vital when it comes to working with remains of non-white people. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, also known as NAGPRA, was created with the intention of providing “a process for federal agencies and museums that receive federal funds to repatriate or transfer from their collections certain Native American cultural items…to lineal descendants” (BLM). Any institution that receives federal funding, other than Smithsonian which has its own laws to try to ensure ethicality, must comply.

Furthermore, certain groups, such as the Manhattan district attorney’s office, have created teams to try and restore stolen artifacts that were obtained or kept unethically and put them back closer to where they were found. However, this itself isn’t free of ethical accusations and questions. Recently, a Greek archaeologist by the name of Christos Tsirogiannis accused the aforementioned district attorney’s office’s antiquities trafficking unit of taking his anthropological discoveries after he “has helped the unit recover and repatriate ancient treasures to their respective countries of origin, providing crucial evidence obtained through his own extensive research” (Alberge, 2023). The goal of the program is to reintroduce ethics in a situation where it was taken away, yet in doing so the district attorney’s office failed to notice their own incompetencies.

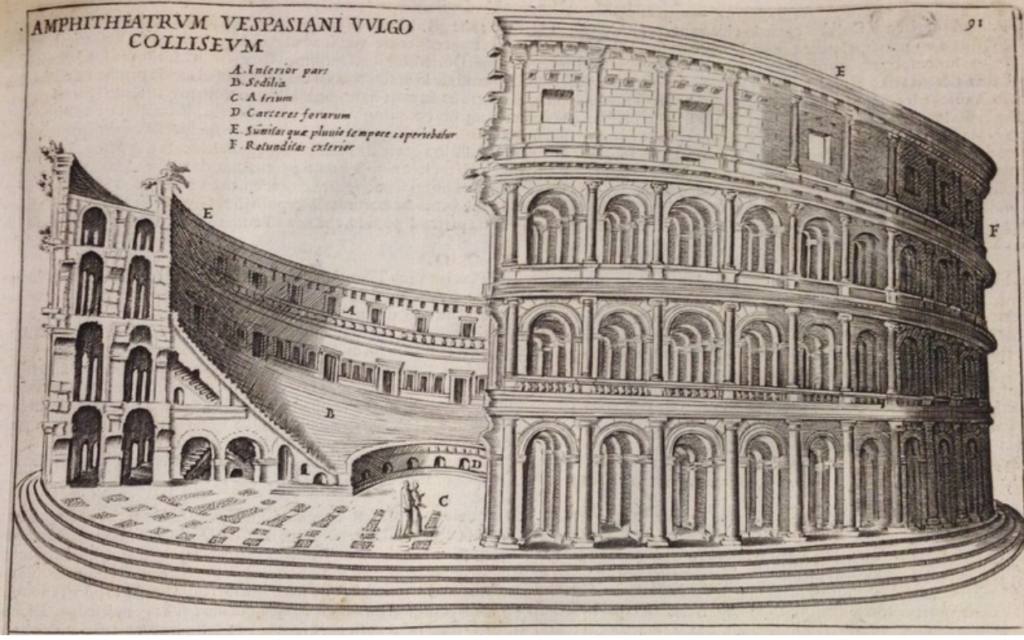

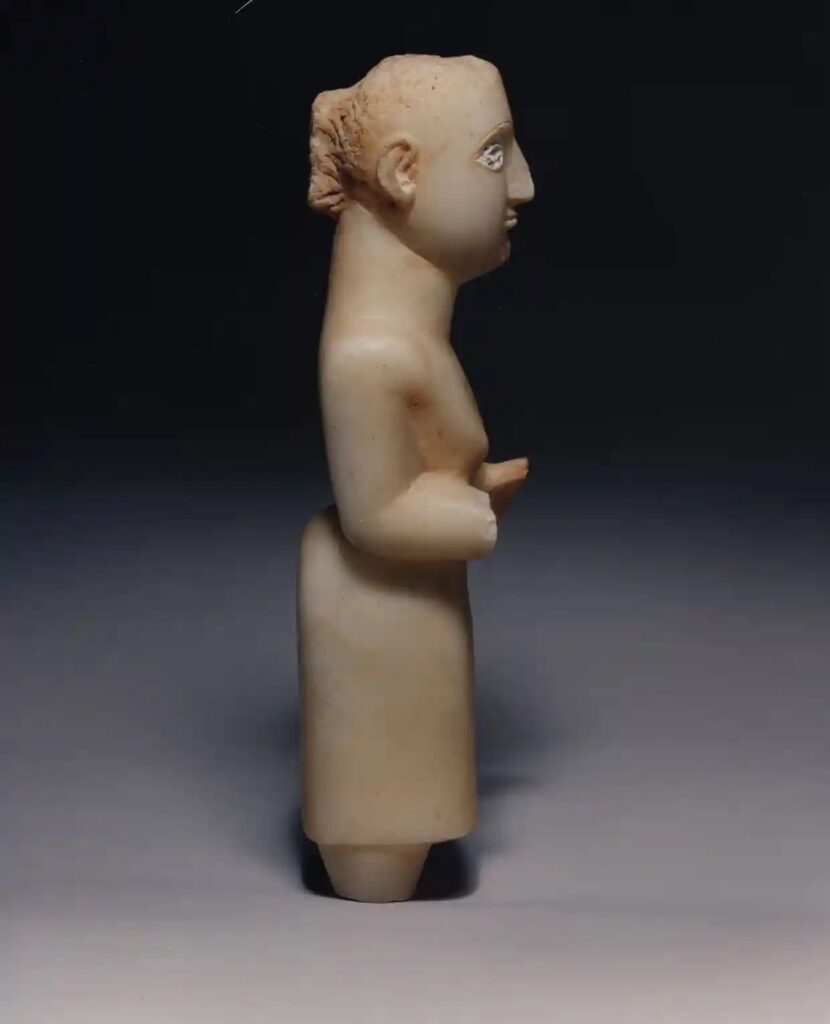

Another question of ethicality arose when “around 2,000 treasures were reported ‘missing, stolen, or damaged’ over a ‘significant’ period of time” (Glynn, 2023) from the British Museum. While, at face value, this seems like a catastrophic atrocity, there has been public backlash. This is because the stolen artifacts were originally obtained by the museum through thievery as well. Because the artifacts were mostly Greek and Roman gems and jewelry, NAGPRA does not apply. Geoffrey Robertson, a British-Australian restitution expert, author, and human rights lawyer, describes the British Museum as “the world’s greatest receiver of stolen property. Tourists should bear in mind that much of the interesting ethnic stuff that’s on display is, in fact, stolen” (Wilder, 2023). This is vital to remember in order to not erase the past and ensure that people question what they see.

While seeing artifacts in museums seems exciting and educational, it’s all lost if those artifacts are stolen or obtained unethically.

References :

Alberge, Dalya. “‘Enough is Enough’: US Looted Treasures Unit Faces Accusations Over Credit.” The Guardian. September 26, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/ sep/26/antiquities-trafficking-unit-archaeologist-christos-tsirogiannis

“Compliance: Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.” National Park Service. January 21, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/compliance.htm

“Ethics in Professional Archaeology.” Society for American Archaeology, 2018. https://www.saa.org/career-practice/ethics-in-professional-archaeology

Glynn, Paul. “British Museum Asks Public and Experts to Help Recover Stolen Artefacts.” BBC News. September 26, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-66921621

“Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act.” Bureau of Land Management. https://www.blm.gov/programs/cultural-heritage-and-paleontology/archaeology/archaeology-in-blm/nagpra

“What Do Forensic Anthropologists and Detectives Have in Common?” Smithsonian. https://naturalhistory.si.edu/education/teaching-resources/anthropology-and-social-studies/forensic-anthropology

Wilder, Charly. “When a Visit to the Museum Becomes an Ethical Dilemma.” The New York Times. February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/travel/museums -stolen-art .html

Further Reading :

https://news.ufl.edu/2023/05/human-dna-everywhere-ethics/

https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1563/isb-buff-case-update-04212021.htm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/terra-cotta-soldiers-631.jpg)