At Durrington Walls, a permanent settlement in Britain dating back to 2500 B.C.E., evidence of feasts offers a new understanding of pilgrimages to nearby monuments(Mowbray 2023). The large site, illustrated in figure 1, is believed to have been the home of those building Stonehenge, which were visited by those from around the British Aisles (Mowbray 2023). The nearby circular gathering site of Marden is also tied to Durrington Walls, displaying the settlement’s significance in early Britain’s culture around pilgrimage, gathering, and celebration (Romey 2019).

At the site, many artifacts of the feasts remain, including 8,500 animal bones, mainly those of pigs (Romey 2019). Researchers found through isotope analysis of pig teeth and jaws that those who gathered at these sites brought livestock from their own regions for the feasts (Morris 2019). While the attendees could’ve reasonably raised the pigs near the feast site, it is presumed that these travelers were required to bring their own food for the feast in order to attend (Morris 2019). It is important to understand the implications of pigs being the animal of choice, as they are considered difficult to travel with (Romey 2019). The difficulty of this journey, which was dozens to hundreds of miles long, makes it more significant that these were pan-British gatherings, not just individual community celebrations or gatherings between neighboring villages (Romey 2019). This offers insight into the organization of the event, as people from far reaching areas of the British Isles were aware of and interested in making the pilgrimage to these stone structures around Durrington Walls.

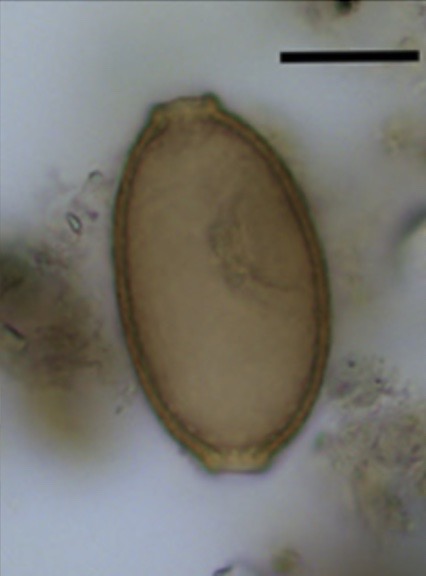

Further research has been done on the diets of those feasting at Durrington Walls involving coprolites, which are fossilized feces (Bonner 2022). In this study, which focused on humans and dogs, researchers found the eggs of several intestinal parasites (pictured in figure 2) which indicate that animal organs were eaten at these feasts, not just the muscular meat (Mitchell 2022). One parasite was found to be a fish worm, which indicates that a dog had eaten a fish (Bonner 2022). This is a surprising finding as not much evidence has been found of fishing during the Late Neolithic period in Britain (Mitchell 2022).

Through multiple means of analysis of the Durrington Walls site’s feast remains, researchers find more than they would through one method. Bone and tooth isotope analysis offers more information on the original locations of those attending pilgrimages, and the coprolite analysis found that people were eating organs and possibly fished, for which there is less traditional evidence (Mitchell 2022). This research of Durrington Walls and its food waste shows how various methodologies can come together to create a better understanding of how and why people made these pilgrimages.

References:

Bonner, Laure. 2022. “Prehistoric Faeces Reveal Parasites from Feasting at Stonehenge.” University of Cambridge Department of Archaeology. https://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/news/prehistoric-faeces-reveal-parasites-feasting-stonehenge.

Mitchell, Piers D, Evilena Anastasiou, Helen L. Whelton, Ian D. Bull, Mike Parker Pearson and Lisa-Marie Shillito. 2022. “Intestinal Parasites in the Neolithic Population who Built Stonehenge (Durrington Walls, 2500 BCE).” Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/parasitology/article/intestinal-parasites-in-the-neolithic-population-who-built-stonehenge-durrington-walls-2500-bce/DD77DA2B94FD3C482A466819CD50EFD7.

Morris, Steven. 2019. “Ancient Britons Travelled Hundreds of Miles to Stone Circle Feasts.” The Gaurdian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/mar/13/ancient-britons-travelled-hundreds-of-miles-to-stone-circle-feasts.

Mowbray, Sean. 2023. “What the Stonehenge Builders Liked to Eat.” Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/what-the-stonehenge-builders-liked-to-eat.

Romey, Kristin. 2019. “Stonehenge-Era Pig Roasts United Ancient Britain, Scientists Say.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/stonehenge-pig-roasts-united-ancient-britain.

Further reading:

https://www.thoughtco.com/feasting-archaeology-and-history-170940

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/terra-cotta-soldiers-631.jpg)