The ancient Chinese accidently invented one of the most widely used weapons. Alchemists in ancient China spend centuries trying to concoct an elixir of life with no success. During the Tang Dynasty, an alchemist mixed 75 parts saltpetre with 14 parts charcoal and 11 parts sulfur, which exploded when it was exposed to an open flame.

At first, China used gunpowder simply to scare or surprise their enemies. When the Chinese realized the significance of what they had invented, they started to use gunpowder to kill instead. The military forces of the Song Dynasty started using gunpowder devices against the Mongols as early as 904 A.D.  The first of these devices was “flying fire”: an arrow with a burning tube of gunpowder attached to the shaft, primitive hand grenades, poisonous gas shells, flamethrowers and landmines. By the 11th century, the Chinese were filling bombs with gunpowder and firing them from catapults. These fire cannons needed two people to carry them and were fired from moving platforms placed near the wall of the enemy city.

The first of these devices was “flying fire”: an arrow with a burning tube of gunpowder attached to the shaft, primitive hand grenades, poisonous gas shells, flamethrowers and landmines. By the 11th century, the Chinese were filling bombs with gunpowder and firing them from catapults. These fire cannons needed two people to carry them and were fired from moving platforms placed near the wall of the enemy city.

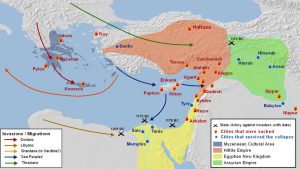

The Song government realized the extreme advantage they had in warfare and tried to keep gunpowder a secret from other countries. In 1076, they even banned the sale of saltpeter to foreigners. Despite all their efforts, knowledge of this new substance was carried along the Silk Road to India, the Middle East, and Europe. By 1280, recipes for gunpowder had been published in the west.

Gunpowder is just another example of how when a new technology is created, the rest of the world must either adapt or become obsolete. This is extremely relevant when it comes to weapons and tools of warfare. If one civilization has better weapons, they will be able to conquer everyone else unless other civilizations learn the technology. This is a constant cycle as civilizations create new technology while also trying to keep up with the new technology of others.

Additional Content:

http://www.monkeytree.org/silkroad/gunpowder/europe.html

Work Cited:

“Flying-cloud Thunderclap Eruptor.” depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/miltech/firearms.htm.

“Flying Fire.” ffden2.phys.uaf.edu/211.fall2000.web.projects/I.%20Brewster/History.html.

“Gun and Gunpowder.” Silk-Road, www.silk-road.com/artl/gun.shtml.

Ross, Cody. “Middle Age Technologies Gunpowder.” Four Rivers Charter, fourriverscharter.org/projects/Inventions/pages/china_gunpowder.htm.

Szczepanski, Kallie. “The Invention of Gunpowder: A History.” ThoughtCo, 23 Apr. 2018, www.thoughtco.com/invention-of-gunpowder-195160.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Gunpowder Explosive.” Encyclopedia Britannica,www.britannica.com/technology/gunpowder.