As anthropologist Jason De León illustrates, “[a]rchaeology is about ‘trying to understand human behavior in the past through the study of what people leave behind’…[n]obody ever said the past had to be a thousand years ago” (Hartigan Shea 2018). When one hears the term ‘archaeology’, they may be tempted to think of the far past whereas it — as De León emphasizes — could refer to even one minute prior.

Today, immigration across the Mexico-United States border (into the United States) remains a prominent issue. De León has studied this area (specifically the Sonoran Desert where many migrants attempt to cross despite its gruesome conditions) in great depth. De León has been recognized by the MacArthur Foundation in 2017 for his expertise in “[c]ombining ethnographic, forensic, and archaeological evidence to bring to light the human consequences of immigration policy at the U.S.–Mexico border” (MacArthur Foundation 2017). Unsurprisingly, De León is one of the only people within the “[range of] archaeologists and material culture specialists” (Hamilakis 2016) to partake in this field.

A Dora The Explorer backpack, among many others, recovered from near the Mexico-United States border and displayed in the “State of Exception” exhibit at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center of The New School (Dobnik 2017).

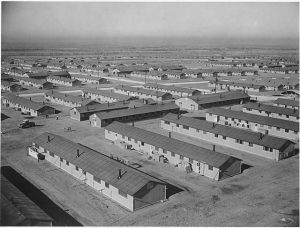

On the Greek island of Lesvos, a similar situation with immigration is occurring. “[M]ore than 500,000 people crossed from Turkey, migrants and war refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, as well as many other Asian and African countries, to [this] island with 85,000 permanent inhabitants” (Hamilakis 2016). In venturing to safer land, “[s]ome of [their] camps…can become substantial and highly organized structures despite their makeshift character, as [seen] in northern Greece” (Hamilakis 2016). These people make do with what little they have, setting up shop and moving onwards — these campsites becoming modern sites for archaeological investigation.

An aerial view of a cramped, makeshift camp in Idomeni on the Greece-Macedonia border, housing approximately 7 thousand people at the time of imaging (Telegraph Video 2016).

In regards to what immigrants jettison in regions like the Mediterranean and the Arizona desert, what is left behind “form[s] worthwhile topics for further reflection and study” (Hamilakis 2016) — and a budding ‘branch’ of archaeology. By locating these abandoned objects, voices and identities are given to otherwise invisible people. This growing problem of today mirrors the movement of past peoples and how they have been studied to understand why they left and where they went. However, currently — the time in which this is an issue — the world has the power to work to reach a logical solution. When looking through their belongings, one can see how these people, regarded as ‘invaders’ and ‘inconvenient’, are human. Understanding that these immigrants are giving up everything to head to safer places for acceptable livelihoods is crucial; they are leaving their past lives to stay alive.

Inevitably, there is no reason to disregard the people leaving their countries for our land of dreams, because they are just like the rest of us.

—

Additional Readings

De León, Jason

2013 Undocumented migration, use wear, and the materiality of habitual suffering in the Sonoran Desert. Journal of Material Culture 18 (4): 321-345. doi:10.1177/1359183513496489.

Papataxiarchis, Evthhymios

2016 Being ‘there’: At the front line of the ‘European refugee crisis’ — part 1. Anthropology Today 32 (2): 5-9. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12237.

Pringle, Heather

2011 The Journey to El Norte. Archaeology, January/February. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://archive.archaeology.org/1101/features/border.html.

Works Utilized

Dobnik, Verena

2017 NYC gallery displays migrants’ backpacks, belongings. The Washington Times, February 10. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/ feb/10/ny-gallery-displays-migrants-backpacks-belongings/.

Hamilakis, Yannis

2016 Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3 (2): 121-139. doi:10.1558/jca.32409.

Hartigan Shea, Rachel

2018 Immigration Archaeology: What’s Left at Border Crossings. National Geographic, August. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/08/embark-genius-jason-immigration-archaeology/.

MacArthur Foundation

2017 Jason De León. MacArthur Foundation, October 11. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.macfound.org/fellows/986/.

Telegraph Video

2016 Watch: Aerial footage of crowded migrant camp on Greece-Macedonia border. Telegraph Video, March 2. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/macedonia/12180807/Watch-Aerial-footage-of-crowded-migrant-camp-on-Greece-Macedonia-border.html.

Images Utilized

Lennihan, Mark

2017 Migrant Belongings Art [image]. Associated Press. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.washingtontimes.com/multimedia/image/ap_migrants_ belongings_art_83724jpg/.

Telegraph Video

2016 Migrant Camp – Aerial [image]. Telegraph Video. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://secure.i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/03587/migrant-camp-aeria_3587034b.jpg.

—