War is not a sustainable part of any society. War has been a leading factor in the downfall of many civilizations. It’s a plague on humanity that seems inevitable in any modern society, and for the most part it is. Why? Agriculture is the culprit.

That’s a grossly oversimplified explanation, but one that does not need to be stretched very much to be justified. Agriculture brought with it sedentary lifestyle. Once the dispute for land and water began, the motives for warfare became unavoidable. The problem is that agriculture is just unsustainable. The most sustainable strategy for a peaceful civilization is that of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The practice of hunting and gathering left very little impact on the environment it took place in. Because of this, the environment in which it took place was able to provide sufficiently enough sustenance for the groups in that area, and when it was no longer a reliable food source the people would pick up and move to another location. The soil was left with little change and animals were hunted in reasonable numbers.

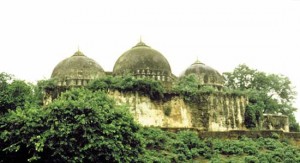

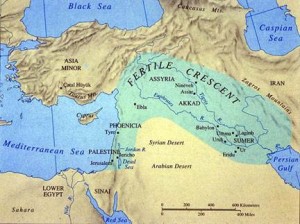

Most people nowadays would consider this to be the lifestyle of a lesser type of civilization with little value, due to contemporary American society revolving around a sedentary style of living. However, it was these very types of societies that were able to outlive Mesopotamia by hundreds of years. Mesopotamia has been nicknamed the Cradle of Civilization and is often times praised for its innovative and intelligent system for irrigation that it developed. This system had fatal flaws though, in that it caused salt to accumulate in the soil and continuously slowed the quality and quantity of crops that could be harvested each season. It goes to show that even one of the most prominent of previous civilizations was not immune to the unsustainable nature of sedentary life.

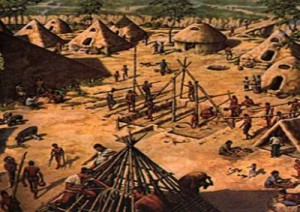

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact time which warfare became more of a norm among societies, but it seems to have become common practice about 5,000 years ago when states began to emerge. States emerge with the development of political units, which are in turn developed as sedentary life and agriculture is established. With the creation of agriculture, there has to be someone in charge, in order to oversee the cultivation and this leads to the village caring for this figure and providing tribute. This trend continues as more political figures are created.

Warfare is not a common practice for hunter-gatherers. They are able to live a peaceful existence because there is little rivalry or even interaction among foreign groups. Without a sedentary life or a political hierarchy caused by agriculture the motivation of “status” for citizens disappears, lessening internal conflicts. Territorial disputes also disappear, for nomadic groups acknowledge that they hold no claim to land. It seems that the more that the past gatherer lifestyle is compared alongside contemporary modern societies, the more the former feels like the most rational option. Reverting back to more more sustainable style would involve changing the lives that we’re accustomed to, and for many that’s a process near impossible.

– Bernardo

image 1: https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcR3JmC4-jLmrrRiTWb_WWPgMIgqYKJG7TrzrVjs_EUZLtxoIK211A

image 2: http://mrkash.com/images/mesopotamia.jpg

![Above is an aerial photograph of Hamoukar which provides archaeologists a better view and interpretation of the site [1].](http://pages.vassar.edu/realarchaeology/files/2013/11/WAR1.png)

![The above image shows various sling-fired missiles found at Hamoukar. The deformed ones resulted from impact after hitting a building or wall. [2]](http://pages.vassar.edu/realarchaeology/files/2013/11/WAR2.png)