How often do you think about archaeology being used to help modern societies use resources better? It’s not like Indiana Jones (sorry, for the clichéd example) went around searching for the mysterious, lost sustainable farming methods. However, archaeology can help us protect our environment and resources by showing us how our predecessors dealt with these issues in their time.

The Channel Islands

(Source: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/anthro/faculty/arnold/california-lab.htm )

The Chumash people of the California Channel Islands are one such culture that can give us important insights to resource management. As early as 9500 B.C. Channel Islanders figured out how to regulate their hunting and fishing so as to not completely decimate their food sources. Historical ecology studies examine the dynamic between these people and their environment from 10,000 years ago onward. It appears that, although there were occasional declines in the populations of various animals, these populations also came back[1]. The Chumash clearly understood how to manage their resources.

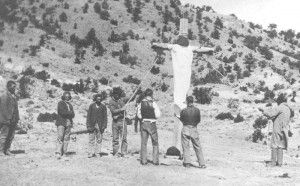

Discoveries of shell middens have taught us a lot about the Chumash’s way of life[2]. Archaeologists have found many different types of projectile points, showing that the Chumash hunted many different types of animals[3]. By diversifying their prey, they had the ability to hunt certain populations while letting others grow.

Different tools and projectile points discovered on the Channel Islands

Interestingly, other evidence indicates that the Chumash and those who came before them did have more impact on the evolutionary diversity of the islands. They brought dogs to the islands! Dogs did a lot of good for the people on the islands, like security, friendship, and hunting assistance. As the numbers of dogs on the islands increased, though, their presence began to impact other animal populations[4]. They killed and drove away many birds and sea mammals. So, although the Chumash’s hunting and fishing techniques are a great example of resource management, their mistakes, like bringing in an invasive species, can also be instructive to today’s society.

Aww! How could a dog impact the environment? Well, transplant about a hundred into an island ecosystem…

(Source: my own photo)

Human impact of this environment has increased significantly in historic times, with oil spills, over-fishing, and other factors. Luckily, the Channel Islands are protected now, but what about the rest of the world? We can learn from the Chumash’s restrained fishing techniques because, although we do have some regulations today, in my opinion, they need to be stricter and focus more on cycling different fish populations. But there has to be more widespread awareness and understanding of this archaeology first.

[1] Torben C. Rick and Jon M. Erlandson, “Archaeology, Ancient Human Impacts on the Environment, and Cultural Resource Management on Channel Islands National Park, California”, CRM Journal Fall 2003: 86-89. Accessed November 14, 2013. http://www.cr.nps.gov/crdi/publications/CRM_Vol1_01_Research_Reports.pdf

[2] IBD

[3] “New Archaeological Evidence Reveals California’s Channel Islands as North America’s Oldest Seafaring Economy”, Smithsonian Science, Last modified March 3, 2011. http://smithsonianscience.org/2011/03/californias-channel-islands-may-have-once-held-north-americas-earliest-seafaring-economy/

[4] John Barrat, “Science Brief: Dog Bones Reveal Ecological History of California’s Channel Islands”, Smithsonian Science, last modified July 6, 2009. http://smithsonianscience.org/2009/07/science-briefdog-bones-reveal-ecological-history-of-californias-channel-islands/