This week our discussion focused on the relationship between Museums and their communities, addressing the key themes of the readings, minority criticisms of the museum, the changes and different approaches that have arisen from their demands, including the founding of community and tribal museums, and the issues that must still be addressed in the future.

The most important idea that ran throughout the readings this week was the desire of native communities to take control of the ownership and representation of their heritage, and to bring the idea of ownership to the general public’s attention. While Clifford describes how, at the Kwagiulth Museum and Cultural Centre, each label contains the phrase ‘owned by’ followed by an individual’s name, Atalay criticizes the NMAI’s exhibition for failing to mention the issues of “cultural and intellectual property rights” and give viewers the opportunity to engage with issues such as “who has the right to control, utilize and profit from Indigenous knowledge, symbols [and] images” (Atalay, 608). These examples, however raised the tricky questions of the ownership and repatriation of rare and precious artifacts. Should scholars and museums give back ownership of objects that they have the means to better preserve for the future, or objects that, through analysis, have the possibility to provide valuable information? Another common theme was the importance of collaboration with Native communities at every stage of the process, in order to create exhibits that counter stereotypes and are relevant and beneficial to the community’s needs. The readings also discuss the importance of highlighting contemporary issues facing indigenous communities, in order to show the public that these are not static, unchanged cultures, but active ones that are both producing new things in art and culture and facing the issue of survival.

In order to fully understand the importance of museum representation, and the criticisms of museums that arose to fight for representation, one must realize the power of the museum as an instrument of civil society. Karp discusses the power a museum has to construct knowledge, provide the public with a certain set of cultural values and define the ideal citizen, which easily excludes groups who do not fit that image. With the catalyst of the civil rights movement, minority groups began to fight for better representation, arguing that museums had an all white staff, served a cultural elite and followed a Western-based knowledge approach that excluded minority perspectives and stories.

As minority groups began to voice these ideas through picketing, demonstration, establishing coalitions, and even vandalism, museums began to focus on their responsibility to their communities. Changes began to occur in subject matter, the exhibition planning process and the variety of activities museums offered. Museums established advisory boards, complied of individuals from the cultural groups they are representing, to aid and approve exhibitions, and have often turned them into permanent consultative positions. One of the most challenging questions of our discussion, however, was if this advisory involvement is enough, or if these boards are merely token positions. While this is definitely a good step, I think that there is more that can be done, in both changing the structure of the museum, and in educating and providing opportunities in the museum field for minority students. While there has been an increased interest in visitor feedback, with the installation of focus groups and comment books, and community outreach and education, with the Philadelphia Museum of Art helping provide ten Latino students with paid internships in the museum field, and many other museums, especially those in urban areas stressing the importance of the “education and vocational training of young people,” and creating mentor-ship programs for students (Simpson), still more can be done.

Another major issue we discussed is how museums address controversial issues. How far does one go in exposing the truth in an exhibition? Atalay’s major criticism of the NMAI is that they did not go far enough in the presentations of the guns and bibles, which were instruments of oppression and horror. Atalay claims that “there can be no stories of survivance without an understanding of the extreme struggle and survival in the face of horrific circumstance,” arguing that the full gory context must be provided in order for viewers to fully understand Native American survivance (Atalay, 610). In this decision of how revolutionary to make an exhibition, however, the curators hope to be offend as little of their audience as possible. Simpson states that the curator tread[s] a tightrope between offending one sector of the community or another: for no matter how warranted a revisionist approach may be, it almost certainly cannot fail to offend those who prefer the nostalgia and glories of heroic myths to the realities of the past,” highlighting how even within one cultural group, it is very difficult to make everyone happy, much less dealing with an entire diverse public. Thus controversy often arises when a museum challenges a popular belief or national ideology, or when there is a misinterpretation of the exhibit’s mission. Simpson believes such issues can can be avoided by clearly stating one’s objectives, close collaboration with native communities, creating open places for discussion, and using vandalism as a starting point for dialog and bringing difficult issues to the public’s attention.

Finally, we discussed the development of community and tribal museums as spaces for communities to take control of the representation of their cultures, to house community activities and to promote their culture. In contrast with cosmopolitan, majority museums, tribal museums challenge the idea of a unified, linear national history, focusing instead on the importance of family relationships and local narratives. Even these community spaces, however, may not be as open as they seem, as certain communities may be given preference over others, and exhibits may not be rotated as often as they proclaim.

Thus, while great strides have been by museums to connect to their public, there are still many issues they must address in the future, including indigenous ownership, minority involvement in the planning process, establishing long term relationships with diverse communities, dismantling their Eurocentric approach, including multiple perspectives, and daring to expose the truth of the colonial past.

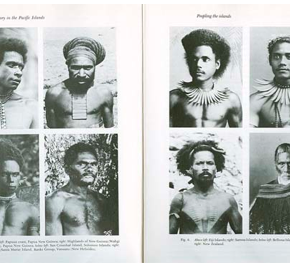

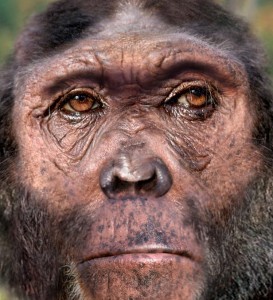

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

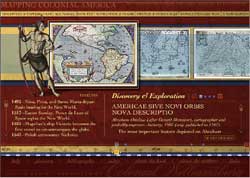

. The exhibit’s home screen has a sidebar with a list of subheadings containing links- the first two of which focus on archaeologists and archaeology as a discipline. These hypermediate the exhibit as constructed, as the bearer of praxis and not just pure information. According to the first of these subheadings, the exhibit was inspired by a Harris poll that assessed the American public’s understanding of archaeology and attempts to move the public’s conception of archaeology away from archaeology and toward an understanding of publicly funded archaeology. The second subheading acknowledges past misrepresentations of early inhabitants of America and discusses the nomination of new National Historic landmarks. Three more subheadings divide the nation into the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast. These subheadings begin with a migratory narrative of the prehistoric people in the area then have further panels focusing on archaeological and geological conclusions about the area and artifacts.

. The exhibit’s home screen has a sidebar with a list of subheadings containing links- the first two of which focus on archaeologists and archaeology as a discipline. These hypermediate the exhibit as constructed, as the bearer of praxis and not just pure information. According to the first of these subheadings, the exhibit was inspired by a Harris poll that assessed the American public’s understanding of archaeology and attempts to move the public’s conception of archaeology away from archaeology and toward an understanding of publicly funded archaeology. The second subheading acknowledges past misrepresentations of early inhabitants of America and discusses the nomination of new National Historic landmarks. Three more subheadings divide the nation into the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast. These subheadings begin with a migratory narrative of the prehistoric people in the area then have further panels focusing on archaeological and geological conclusions about the area and artifacts.