I’m so glad that Anne posted about the Titanic because I’ve been meaning to write a little something about it ever since I saw Titanic 3D a couple weekends ago.

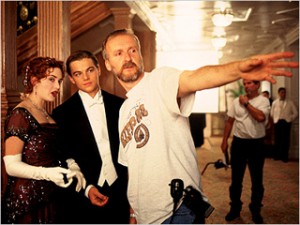

Now, I don’t mean to claim that James Cameron is an archaeologist HOWEVER I am really interested in some archaeological ideas Cameron presents in his film Titanic.

Now, I don’t mean to claim that James Cameron is an archaeologist HOWEVER I am really interested in some archaeological ideas Cameron presents in his film Titanic.

I first saw the film when I was in elementary school and all I really remember is thinking how sad it was that Jack died in the end and how crazy the old woman was for throwing the necklace back into the sea. Watching it now, especially after having learned a bit more about archaeology this semester, I have a slightly different mindset.

Both in Avatar and in Titanic Cameron does a phenomenal job of portraying the treasure-hunting greedy American as insensitive and as one who dehumanizes the artifacts and land that are in his way (the RDA corporation and Brock Lovett respectively). In class, we’ve talked a lot about this perception of archaeologists. This view, commonly shared among some Native American groups, who have traditionally viewed archaeologists as grave-robbing treasure-hunters, has hindered archaeological projects and has led to a mistrust of archaeologists by some Native Americans. When the treasure-hunters in the film explain how the ship sunk to the modern day elderly Rose, they are pretty insensitive:

Lewis Bodine: [narrating an animated sequence of the Titanic’s sinking on a TV monitor] Okay here we go. She hits the berg on the starboard side, right? She kind of bumps along punching holes like Morse code, dit dit dit, along the side, below the water line. Then the forward compartments start to flood. Now as the water level rises, it spills over the watertight bulkheads, which unfortunately don’t go any higher than E deck. So now as the bow goes down, the stern rises up. Slow at first, then faster and faster until finally she’s got her whole ass sticking up in the air – And that’s a big ass, we’re talking 20-30,000 tons. Okay? And the hull’s not designed to deal with that pressure, so what happens? “KRRRRRRKKK!” She splits. Right down to the keel. And the stern falls back level. Then as the bow sinks it pulls the stern vertical and then finally detaches. Now the stern section just kind of bobs there like a cork for a couple of minutes, floods and finally goes under about 2:20am two hours and forty minutes after the collision. The bow section planes away, landing about half a mile away going about 20-30 knots when it hits the ocean floor. “BOOM, PLCCCCCGGG!”… Pretty cool, huh?

Old Rose: Thank you for that fine forensic analysis, Mr. Bodine. Of course, the experience of it was… somewhat different. (reference here)

Rose then proceeds to explain her personal experience on the Titanic. This oral history serves to humanize the search bringing life back to the artifacts the treasure hunters have collected including a hand mirror and a butterfly hair accessory. This is important in archaeology. The objects on their own and out of context (in the film they were presented on a table) seem to just be old objects from a sunken ship. However when brought to life by a personal experience or story and put into context of use and purpose, a viewer can have a totally different and emotional response to seeing and interacting with that object.

Rose then proceeds to explain her personal experience on the Titanic. This oral history serves to humanize the search bringing life back to the artifacts the treasure hunters have collected including a hand mirror and a butterfly hair accessory. This is important in archaeology. The objects on their own and out of context (in the film they were presented on a table) seem to just be old objects from a sunken ship. However when brought to life by a personal experience or story and put into context of use and purpose, a viewer can have a totally different and emotional response to seeing and interacting with that object.

After Rose shared her story about surviving the shipwreck, the main treasure hunter, Lovett, says to Rose’s granddaughter, “Three years, I’ve thought of nothing except Titanic; but I never got it… I never let it in.” (ref)

I think what he meant here is during these past few years he has been meticulously researching the event and searching for treasure on site only really viewing the Titanic in an objective scientific sense. He viewed it, in a way, as intangible event instead of viewing the ship itself as an artifact marking a serious tragedy. The ship had its own life, significance, and culture and was much more complex than he may have completely realized. The site itself is essentially a mass grave for over 1,000 people. To someone removed from the event, that number may just seem like a statistic. However when presented with the stories of the people it personally affected, the number may illicit a much more emotional response and deeper understanding of what the sinking of the Titanic really meant.

And now I think I understand why Rose threw the necklace into the ocean: because it belonged with the ship and the rest of the artifacts from the site. It belonged in the earth under the ocean, not with treasure-hunters, not in a museum, not even with her.

This is a concept that I had been struggling to completely grasp. I guess growing up the way I did, attending public school in northeastern USA up until Vassar, I kind of felt like it was the archaeologist’s right to dig up essentially anything for the sake of knowledge and preservation. And I’m not trying to say that I didn’t have a good public school education because I really did, it’s just that archaeology wasn’t really the main topic of discussion in any of my classes. It wasn’t until I took this course that I realized that archaeology and archaeological excavations are not as simple as finding treasure and unearthing mysteries in our history, as I had always assumed. In the case of some Native American communities, it is natural and right for humans and objects to return to the earth when the time has come for them to do so. So it’s hard, I think, to really determine if archaeologists have the right to dig up sites for the greater good of knowledge or if they should leave the site be. Collaboration between archaeologists and the community that the archaeologists’ research affects is, I think, a step in the right direction. Constantly reminding the archaeologist of the human aspect of their research and how that affects that modern-day community can enrich the research project and ultimately potentially have a greater and more significant impact.