This week our discussion centered on the use of visual and new media in public archaeology. This blog already provides examples of a wide range of alternative tools for communicating archaeology: blogs, digital narratives created through Voicethread, Youtube videos, and online museum exhibits to name a few. What possibilities do media outside of the traditional academic categories open for doing public archaeology? What challenges to alternative media present?

General consensus seems to be that new media are a powerful tool for communicating with the public- more compelling and interesting than traditional texts. New media are more accessible both to readers, who have the ability to give direct feedback, and to authors, who can be published online without much of the gatekeeping of print.

Chip Colwel-Chanthaphonh saw the potential in an online archaeology exhibit to reach a wide audience while also providing not just information, but an experience that steeped the viewer in culture through music, image, video, text and art. For him, “alternative” archaeology is best matched with alternative media. Ruth Van Dyke explores other possibilities in new media, including experimental video that challenges the conventional codes used in archaeology documentaries, hyperlinked web sites that force the viewer to navigate his or her own course.

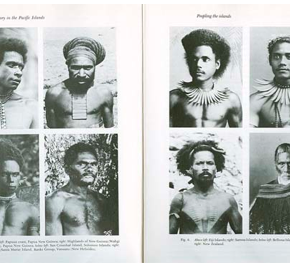

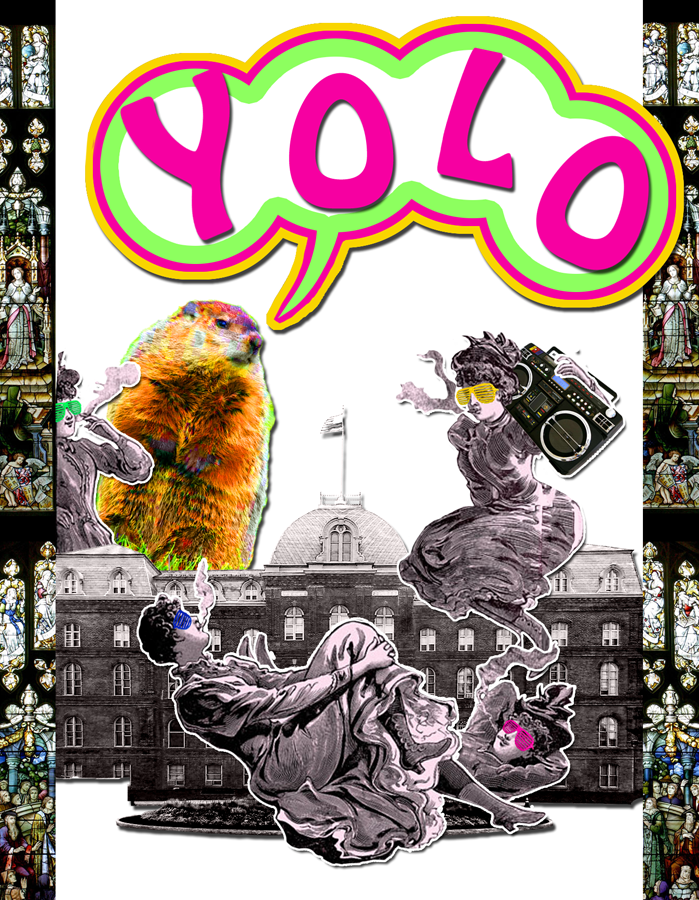

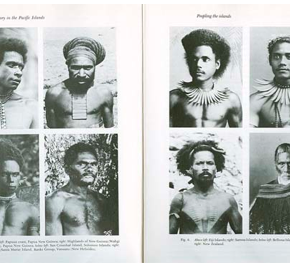

Though critical movements in archaeology have led to a deeper self-consciousness in the producers of archaeological knowledge when writing texts, Sara Perry sees a lack of critical examination in the use of images. She uses the example of visualizations used for the peopling of areas as a troubling example in which contemporary and objectivizing conceptions are projected on the past and legitimated through the unquestioned mode of image. She suggests remediating such images to  force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

The texts mentioned here focus on how new media can be and has been used to communicate archaeology, but only in one direction, from the archaeologist to the non-archaeological public. Could video, interactive programming, or other non-traditional forms ever be considered appropriate for communication strictly within academic circles?

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.