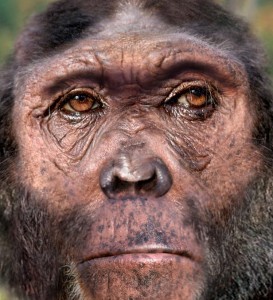

Per this week’s readings on the power of visuals, I thought I’d post something about paleoartist Viktor Deak:

Deak has created innumerable models of early humans for museums around the world, and has been featured in NOVA’s human origins documentary, Becoming Human. He works with sculpture and digital imaging, often combining mediums to get the hyper-realism he desires (e.g. taking a picture of a sculpture and then photo-editing in minor details). His computer models have also been used to as starting points for simulating the movements of the specimens in question. Deak always begins his work by examining the physical fossil remains, then works his way upwards from a cast of the fossils, laying on muscle structure, cartilage, and finishing up with skin, eyes, and hair. He defines his work as inherently grounded in science: “If there’s no science to begin with, we unfortunately don’t get to do any art.” (New York Times, Envisioning Our Distant Past, 2009)*

However, just from his murals and landscapes (such as the series “Lucy’s World”), it is evident see that human origins as a concept captured Deak’s imagination in a thoroughly un-scientific way, and this (though, far be it from me to pass judgment) is a good thing. In this sense, Deak’s work connects back to our discussion of the power of creative agency and imagination in creating formative epistemologies, even if the modes of learning we are discussing are purely visual. You can’t hypothesize about what something looks like unless you know how to hypothesize (that is, imagine) what something might look like. As colonized archaeology takes away the ability to create new trains of logic from material evidence by limiting the archaeologist’s scope before they even get to the dig, science that is grounded in reiteration and rearticulation without imagination is inevitably a regurgitation of the same information. Thus, imagination becomes a mode of “enskilment”. (Perry 2009)

Deak’s own fascination with his subject material is telling in regard to the ways museum practice and archaeological displays capture the hearts and imagination of the public: “Once the eyes are in the face and there’s a face on that thing, I feel as if there’s a chasm of time that’s eliminated. I wish I could travel in time to look at these things, but I can’t. [recall Bolter and Grosin’s discussions of immediacy] So the best thing I can do is to try to bring them to us.” (NOVA, Building Faces From Fossils, 2009; embedded below)**

[media id=1 width=600 height=440]

*If you choose to watch this interview, be forewarned of the New York Times’ choice of a didgeridoo for representing a “pre-modern human ambiance”.

**Come to think of it, this soundtrack is pretty jarring as well.

. The exhibit’s home screen has a sidebar with a list of subheadings containing links- the first two of which focus on archaeologists and archaeology as a discipline. These hypermediate the exhibit as constructed, as the bearer of praxis and not just pure information. According to the first of these subheadings, the exhibit was inspired by a Harris poll that assessed the American public’s understanding of archaeology and attempts to move the public’s conception of archaeology away from archaeology and toward an understanding of publicly funded archaeology. The second subheading acknowledges past misrepresentations of early inhabitants of America and discusses the nomination of new National Historic landmarks. Three more subheadings divide the nation into the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast. These subheadings begin with a migratory narrative of the prehistoric people in the area then have further panels focusing on archaeological and geological conclusions about the area and artifacts.

. The exhibit’s home screen has a sidebar with a list of subheadings containing links- the first two of which focus on archaeologists and archaeology as a discipline. These hypermediate the exhibit as constructed, as the bearer of praxis and not just pure information. According to the first of these subheadings, the exhibit was inspired by a Harris poll that assessed the American public’s understanding of archaeology and attempts to move the public’s conception of archaeology away from archaeology and toward an understanding of publicly funded archaeology. The second subheading acknowledges past misrepresentations of early inhabitants of America and discusses the nomination of new National Historic landmarks. Three more subheadings divide the nation into the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast. These subheadings begin with a migratory narrative of the prehistoric people in the area then have further panels focusing on archaeological and geological conclusions about the area and artifacts.