Classical archaeology does not have the most reputable status in the history of archaeology; it has overlooked much of ancient Greek society because of its preoccupation with the treasures of the elite. Looters and treasure-seekers have given the discipline a bad name, as have the biased analyses of looking to prove myths and the narrow aesthetic focus on monuments. Over the past forty years, though, Sofia Voutsaki argues that much has changed for the better. Voutsaki states that the “Great Divide” between classical archaeology and other forms of archaeology, such as prehistoric and medieval archaeology, is closing; classical archaeology is no longer only “concerned mostly with high culture, monumental temples, artistic masterpieces and urban elites.”[1]

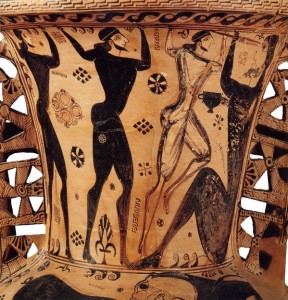

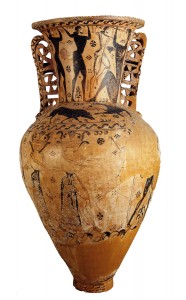

Classical archaeology has come a long way from its origins in pillaging, but there are still several short-comings in the archaeological log. Classical archaeology could be charged with breeding carelessness within its own field: “There is a tendency for well-known objects of high aesthetic merit to lose their archaeological and cultural contexts when placed in the broad narrative of Greek art history.”[2] Take for example the Polyphemus amphora from Eleusis[3] – it is given precedence in major art history books for being a classic 7th century BCE style funerary vase, and yet it is rarely mentioned that this is a child’s coffin.[4] By placing the object in the larger context of art history the vase has lost much of its human significance; classical archaeologists only analyze the vase for style, form, and function to give the piece meaning within the pre-determined chronological spectrum of vases. Studies of this kind, however, ignore the social meanings of the artifact, a problem object biographies try to correct.

Object biography “seeks to narrate the accrual of social meanings over the lifespan of an artifact. The approach is attractive for its narrative structure and post-processual emphasis on the active nature of material culture.”[5] Object biographies confirm classical archaeology’s growth in the last 40 years. Not only does this academic practice seek to use its knowledge for more than classifying objects into art historical categories, it seeks to understand every aspect of society within its cultural context; classical archaeology has moved past mere cultural historical study and has begun to emphasize post-processual investigation.

The culture history approach creates a normative model of culture that ignores the processes of change over time.[6] The processual approach addresses these processes, but again is normative and ignores individual agency. Post-processual approaches, such as object biography, strive to explain the importance of non-material factors in society. However, one approach is not more important than the other instead they should be built on top of each other to gain a complete understanding of human culture. Classical archaeology’s ability to address all three of these approaches proves that it has transitioned from treasure hunting to new humanistic approaches to better understand all aspects of Ancient Greek culture.

[1] Voutaki, Sofia Pg. 21

[2] Langdon, Susan. Pg. 579

[4] Langdon, Susan. Pg. 579

[5] Langdon, Susan. Pg. 579

[6] Ashmore, Wendy. Pg. 40

Images from:

<http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/tools/pottery/painters/keypieces/protoattic/eleusis.htm>

Citations:

Ashmore, Wendy. Sharer, Robert. Discovering Our Past: A brief introduction to Archaeology. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; New York, New York. 2014.

Langdon, Susan. “Beyond the Grave: Biographies from Early Greece.” American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 105, No.4. Oct., 2001. Archaeological Institute of America. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/507408>

Voutaki, Sofia. “Greek Archaeology: theoretical developments over the last 40 years.” TMA jaargang Mediterrane Archeologie No. 40. 2008. Pg. 21-28. <http://www.academia.edu/2099301/Greek_archaeology_theoretical_developments_ over_the_last_40_years# >