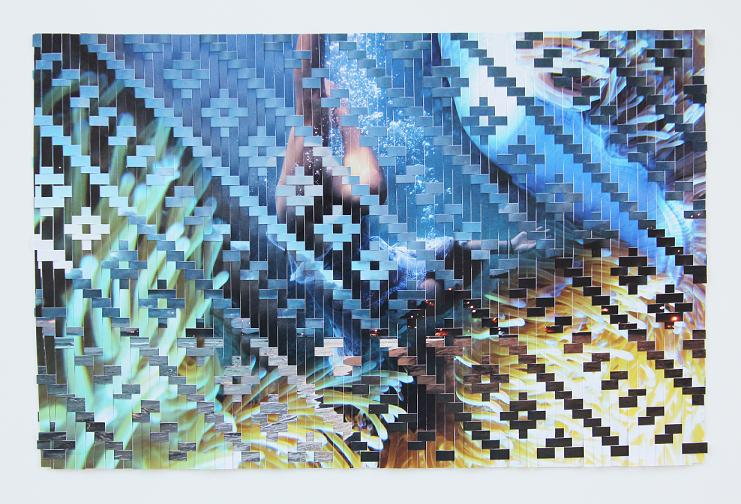

Sarah Sense Weaving Water

Pitaloosie Saila Strange Ladies, 2006

Vassar College’s Art History program has been known for its progressive contemporary art programs, but for this experiment interdisciplinary efforts were called for. In fact, the Art department was not the one to call for this experiment – the Native American Studies department did the majority of the preparatory work under Professor McGlennen. It took two years, but the class, Decolonizing the Exhibition, was a huge success; pulling from the Art History department many of its students. In its novelty the exhibition held a panel for students inside and outside the class to hear from the forces that put the exhibition together. One panelist was McGlennen herself; another, Edward Guarino, a collector of Indigenous art and friend of Vassar; third, a student: Pilar Jefferson; and lastly, Sarah Sense, a Native American artist.

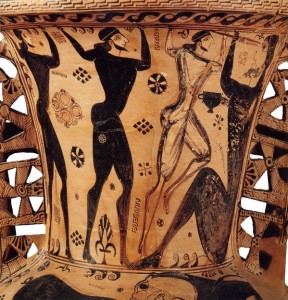

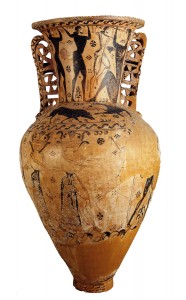

All four panelists explained the goals of the course as related to the art/museum world, as well as the education world. The panelists expressed their concerns that they had never learned about the contemporary Native American art movement in their Art History educations and when they came into contact with Indigenous art in the museum it tended to focus on older generations in an anthropological manner.

The way this exhibition was executed – through the Native American Studies department instead of the Art department – allowed for a new approach to contemporary Indigenous art installation. Jefferson and McGlennen both explained the limitations and challenges of such an exhibition, especially in a museum, where traditionally Indigenous art is displayed in an anthropological manner, stopping right around the 20th century – as if Indigenous art died out, as if Indigenous people died out. This tradition of displaying only older generations of Indigenous art and artifacts in art museums reinforces the colonialist view that Indigenous people died out when the Europeans came.

McGlennen and her students stressed this problem in their working on the exhibition, in hopes that they could destroy this traditional view of Indigenous art. They picked contemporary art because it was so rare in the art museum and it exemplifies the struggles that Indigenous people encounter, sometimes the same problems as older generations, often compounded with new problems. They also expressed interest in being as true to the artists in their wall labels as possible because none of the students were Indigenous themselves. They began each label with a quote from an Indigenous person, always conscious of their job as allies.

The most important theme in this exhibition was the idea of “the story.” It seemed to all four panelists that Indigenous art sought to tell, express, or continue a story. Sense and McGlennen, both Native American, agreed with this idea; Sense many times told a story herself in hopes to explain her art to the students. McGlennen stressed, though, that the exhibition’s purpose was not to simply display the art in a non-anthropological way, but to help display the art without adding America into the story. Even if America affected the story, the story was never about America.

http://www.trebuchet-magazine.com/sarah-sense-weaving-water/

http://fllac.vassar.edu/exhibitions/2013-2014/decolonizing-the-exhibition.html

http://info.vassar.edu/news/announcements/2013-2014/131204-inuit-exhibit.html