It’s difficult for people to plan for the future. It’s so much easier to be so focused in the present that one does not realize that to make a better future one has to be cognizant of what is currently happening around them. And, not surprisingly, looking into the past can help change and perfect what is happening in the present, therefore creating a better future. It’s pretty simple, but then comes the issue of not only knowing what happened in the past, but knowing how it affected communities in the present so that we can be proactive in planning for a better future. Are you surprised to hear that the answer to the question is (drum roll….) archaeology!

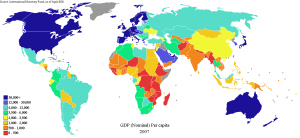

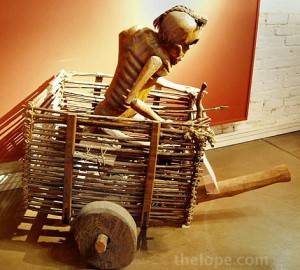

By using the archaeological record, which is growing over time, archaeologists can discover an enormous amount of information about past cultures and how their ways of life affected their communities. By studying agricultural techniques of past societies, their failures and achievements, we can alter the way we use agriculture to be more sustainable. For example, by studying the past cultures who came up with the three-field system of agriculture, where land and what is being grown is rotated to allow the nutrients to replenish, archaeologists found that this system works and benefits the communities; thus, today we have a better understanding of how to rotate crops and fields to keep the soil fertile. This understanding makes us more sustainable in the long run, our future. Understanding the conflicts that caused wars between past societies can assist us in avoiding these conflicts, and prevent unnecessary wars. A poignant example is wealth distribution; when unequal, we end up with the haves and the have nots, with a top 1%. This frequently leads to resentment, which leads to conflict and war. Therefore, archaeologists can evaluate how past societies best distributed resources to create the best environment for all. Looking at how cities were planned out and maintained, and consequently if they could survive disasters can help us plan out current cities in the most logical and beneficial manner to support development and growth. Archaeology has a place in many contemporary social issues that need to be evaluated in the present to preserve the future.

Everyone knows that archaeology is the study of the past. However, most people don’t understand that the knowledge archaeologists learn from the past can be applied to the present to better the future. The excavation and “cool” artifacts the archaeologists discover seem to steal the image for archeology. It’s important to understand, however, that what archaeologists learn from artifacts, and apply to the present, is what makes them truly valuable.

Works Citied:

http://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/showthread.php?205809-Saga-of-Halland/page2

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2010/11/18/ipcc-official-“climate-policy-is-redistributing-the-worlds-wealth”/

Further Reading:

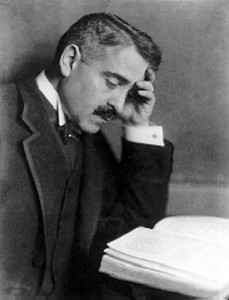

Sabloff, Jeremy A. Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast, 2008. Print.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three-field_system