When you think of archaeology, what comes to mind—treasure, gold, ancient mummies, lost civilizations? While this is not what modern archaeology is (despite the many stereotypes surrounding the field), it is how archaeology began. Evolving from both curiosity and greed, archaeology has blossomed, though only recently in the 19th century, into a widespread discipline of discovering and preserving the past. Thus, compared to most scientific fields, archaeology is still relatively young and developing.

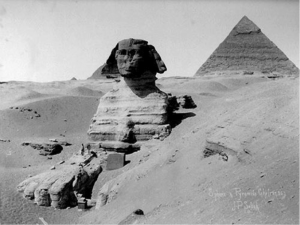

Before the Renaissances of the 14th-17th centuries, there was little interest in learning about the past. People, like the Romans, were only interested in collecting artifacts or finding treasure. During the time of the Roman Empire, regions in the Mediterranean were looted and destroyed in search of artifacts to beautify palaces. However, as more discoveries were made, some wanted to look past monetary values and learn about the past cultures. For example, in the 15th century B.C., King Thutmose IV of Egypt ordered the excavation and restoration of the Great Sphinx. Once completed, he left a stone tablet, known as the Dream Stele, so that others could understand and learn from his discovery. This as well as other excavations set the groundwork for what would eventually become archaeological research.

However, as the number of archaeological finds grew, so did the number of interpretations of past. Evidence began to disprove the long-held view of the Old Testament creation story. However, disliking this, most simply ignored evidence that was brought to light. It was not until Charles Lyell’s work (about TWO centuries later) that the theological view of creation was successfully rejected. Lyell proposed the theory of uniformitarianism, stating that the processes in place today are the same ones from the past. Along with Lyell’s theory, human tools, dating back from far longer than 6,000 years (the estimated age of earth according to the Old Testament), were discovered with extinct animals. With that, the search for link between the past and present civilization of Europe began.

By the 19th century, archaeology was becoming a professional discipline. People became full-time archaeologists, using facts rather than speculation to understand the past. Archaeologists began using models to put together puzzle pieces of the past. The first well-known model was the three-age system—the belief that civilizations developed gradually through the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. However, this model could not be applied to the Americas (which lacked historical record). Thus, archaeologists began using the unilinear cultural evolution model—which stated that civilizations were barbaric before transforming into a civilization. Yet, with this model came a great deal of ethnocentrism—the belief that your way of life is the best way of life. Simply stated, this model was bias. Because archaeology developed in a Western culture, it centered around the idea that Western culture was superior in evolutionary development. However, modern archaeologists now recognize the dangers of their own bias and try to eliminate it from their work.

What began treasure hunting has developed into a complex field that works to fight ethnocentrism, preserve past culture, and learn ways to better the future. That is archaeology.

Links:

Ashmore, Wendy, and Robert J. Sharer. Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology. New York: McGraw- Hill, 2012. Print.

Image 1: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sphinx/stel-05.html

Image 2: http://catalystruser.tumblr.com/post/12286376592/charles-lyell-uniformitarianism-and-evolutionary

Further Reading: http://www.age-of-the-sage.org/archaeology/history_of_archaeology.html