When did archaeology become the respected profession it is today? What gives archaeologists the authority to excavate in a land that is not their own? Archaeology has transformed significantly throughout the years into a respected science that teaches us about the past and how we have progressed into today’s society.

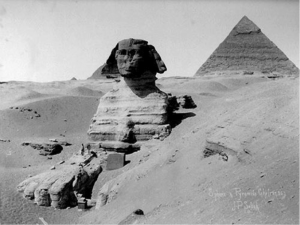

Civilizations, modern and old, have always been fascinated with the people who sewed and toiled on the land before them. Even thousands of years ago, people wanted to understand the past. For example, during 15th century B.C, an Egyptian pharaoh by the name of Thutmose IV led the first excavation of the Great Sphinx at Giza. With archaeological fascination growing and new artifacts being excavated at every turn, archaeology has progressed from antiquarianism (basically treasure hunting) to using the scientific method to investigate and understand more about the people of the past (Ashmore 26-27).

Indigenous archaeology is a branch of archaeology that collaborates with the people of the area being researched. Although this method of archaeology considers the heritage of the people living in the area of study, many indigenous people do not want their ancestors’ “things” being excavated or disturbed. Because of this, indigenous people have fought for change in the way archaeologist conduct their research. Every year more and more indigenous people are making their voices heard, some even becoming archaeologists.

Considering all the modifications archaeologists have made to their science, the debate of to whom the cultural artifacts belong, remains an ongoing issue. Those who sympathize with the native peoples have worked diligently to return ownership of graves and artifacts uncovered, back to them. Although there seems to be a large effort in assisting the indigenous people, there are still some who believe archaeological research is causing them harm.

This historical debate will most likely continue on as long as archaeology exists. Indigenous archaeology is one solution that tries to level this debate, but this type of archaeology is not yet fully established. It continues to change and develop with the collaboration of both indigenous people and archaeologists.

Archaeological practices have come a long way since Thutmose got curious about the Sphinx at Giza, and it will continue to transform in an effort to return the culture to as many groups of people as it can. Challenges still remain, but archaeology has become a source of great understanding and respect for the past. From the lowliest cracked peace of pottery to the great Sphinx at Giza, archaeology has opened a world of understanding about the past. Every little piece of history holds a story, and possibly even the key to understanding an entire civilization. There is never old news in archaeology; it will always continue to unearth new mysteries and it will always attempt to solve them.

-Ava Sadeghi

Links:

Image 1: http://sacredsites.com/africa/egypt/images/sphinx-1900.jpg.

Image 2: http://news.mongabay.com/bioenergy/2007/09/researchers-explore-why-conservation.html

Ashmore, Wendy, and Robert J. Sharer. Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology. New York: McGraw- Hill, 2012. Print.

Atalay, Sonya. “Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice.” The American Indian Quarterly 30.3 (2006): 280-310. Print.

The question of ethics in archaeology is indeed a fraught one, especially when one considers anthropology’s often-flagrant disregard for the desires and rights of native peoples in the early days of the discipline. How can we begin the right the wrongs of the past and set an ethical precedent for archaeological research going forward? The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) attempts to make headway with this issue, by giving descendant communities recourse to reclaim human remains and associated burial goods dug up in the past, as well as to protect sacred burial sites from excavation. In some countries, the United States included, archaeologists are legally obliged to collaborate with native groups. Many archaeologists also consider collaboration beyond the bare minimum to be an ethical imperative; for example, I participated in field schools in Northern California in the summer of 2011 that included indigenous students as crewmembers and invited tribe leaders to supervise our work. While these measures may not completely counterbalance the privilege – economic, academic, and racial – inherent in academic archaeology, indigenous anthropology will continue to evolve, as you say in your post. Present efforts, at least, are a step in the right direction.

If you’re interested in learning more about NAGPRA, visit the official website:

http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/FAQ/INDEX.HTM