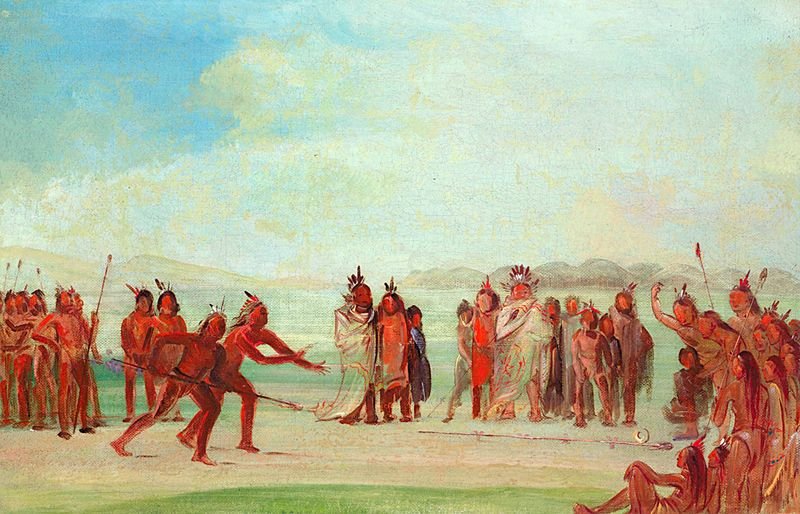

The game of lacrosse is another game along with Chunkey and Stickball, that Native Americans created and played, that still lives on prominently today. In its early Native American forms, lacrosse was played with a wide range of rules and strategies that differed in different areas, but across the board the game was played with wooden sticks, oftentimes with nets attached to them and with a ball made from deer hide. The Haudenosaunee were the original creators of the game, and played it with teams of between 100-1,00 men, on borderless fields. The original form of the game tended to be quite violent with broken arms and legs being a frequent circumstance, and games could last even span multiple days. Much like Chunkey and Stickball, lacrosse games were played to prepare tribes for war, as well as being seen as a social event where tribes would get together for trade and fun. Tribes would often play lacrosse in order to settle territorial disputes, while keeping intact diplomacy between tribes and avoiding warfare and the loss of human life. Often Native Americans would even gamble on lacrosse games, and “some would not hesitate to wager their wives, children, and themselves into servitude.” (Aveni).

Figure 1: Image of large lacrosse game with many players on field without boundaries (Vennum Jr).

Within the lacrosse world, it is commonplace to refer to lacrosse as “the medicine game”, or “the creators game”. This comes from the belief of the Haudenosaunee people that the game was a gift from the creator and was to be played for the creator. It is said that the act of playing the game has a medicinal effect and is said to be able to heal the sick. This belief in the medicinal powers of the game of lacrosse carries on as the game has evolved and the present day Haudenosaunee continue to play the game that was given to them by the creator, with its medicinal nature always in mind.

It is Haudenosaunee tradition for children, when they are born to be given a lacrosse stick with a shaft made from shagbark hickory that is repeatedly dried and steamed until it is bent like a shepherd’s crook. Next, sticks are cut down to size, and the pocket is made from leather or rawhide. These sticks are supposed to stay with them their entire lives and when Haudenosaunee lacrosse players die, they are buried with their stick by their side. As the game of lacrosse has grown and spread beyond the Haudenosaunee nation, equipment and sticks have changed and in present day lacrosse, most players opt for a metal shaft and plastics head with a synthetic pocket, but many present day Haudenosaunee lacrosse players choose to continue the tradition of playing with the wooden stick in honor of the game and it’s history within their culture.

Figure 2: Team Iroquois Lacrosse Players with Traditional Sticks at 2014 World Games. (Maracle, 2023).

Reference List:

Kennedy, Lesley. November 19, 2021. “The Native American Origins of Lacrosse.” History.com. https://www.history.com/news/lacrosse-origins-native-americans.

Aveni, Anthony. “The Indian Origins of Lacrosse.” The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site. https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/winter10/lacrosse.cfm.

“Brief Origin Of Lacrosse.” Nabb Research Center Online Exhibits. https://libapps.salisbury.edu/nabb-online/exhibits/show/native-americans-then-and-now/native-americans-and-lacrosse/brief-origin-of-lacrosse

Maracle, Candace. July 1, 2023. “Master lacrosse stick maker Alfie Jacques passes on tradition before dying.” CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/alfie-jacques-onondaga-haudenosaunee-traditional-wooden-lacrosse-stick-1.6889893

Vennum Jr., Thomas. “The History Of Lacrosse.” Brooklyn Lacrosse Club. https://www.brooklynlacrosse.org/lacrosse-history

Further Reading:

The Making of a Wooden Lacrosse Stick: https://eopsports.com/the-making-of-a-wooden-lacrosse-stick/

Timeline of the History of Lacrosse: https://worldlacrosse.sport/the-game/origin-history/