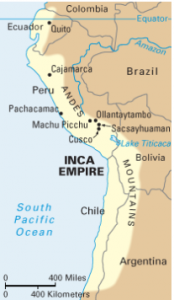

What we have learned and use from ancient civilizations? If they helped to create our foods, we should use some of their same farming practices right? According to the article by Cynthia Graber, the Inca were able to use the Andes Mountains (Figure 1) to get more water through canals. (Graber 2011) She also says, the Inca cultivated many variations of the vegetables we use today, such as, potatoes, quinoa, and maize. (Graber 2011) Was this because of their climate? The structured agriculture?

Figure 1

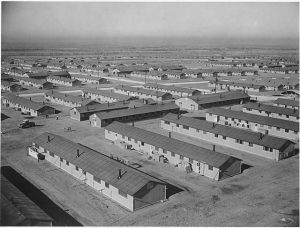

The Inca Empire have left a lot for archaeologists to explore and even experiment with. (Figure 2 Moray Ruins 2018) Kaushik’s article says, the Incas were truly ahead of their times. According to Archaeologists, these huge stone depressions are in the land, to cultivate the different crops. (Kaushik 2013) Kaushik describes, in the article, about how these circular terraces are so well designed, no matter how much it rains, these beds never flood. They drain perfectly. (Kaushik 2013)

Figure 2

Looking at these vast circular terraces and learning that they had more than three crops to cultivate. The Incas were true genius’ to create such a landscape. According to Carolyn, the land wouldn’t get as much sunlight and there could be a 27* difference from the bottom to the top. (Graber 2011) The Inca lived in South America, (Figure 1) which means there wouldn’t be a very long growing season. The more crops the Inca could grow at a time, the better. Many archaeologists decided to explore more about the Incas agricultural process, especially the water systems.

“Over the years, Kendall learned how the Inca builders employed stones of different heights, widths and angles to create the best structures and water retention and drainage systems, and how they filled the terraces with dirt, gravel and sand.” (Graber 2011) Kendall speaks about terracing and how people in Mountainous regions will practice these methods in order to conserve water. (Graber 2011) In this article, Kendall goes on to discuss how after the canals were irrigated, they were found six months later damp. This shows how sophisticated the canals were. (Graber 2011)

Now the question is, what can we change about our own farming methods? According to Carolyn’s article, Archaeologists have found many of the canal systems and the people who live there are helping to restore this old way of gathering and collecting water. (Graber 2011) Maybe once this process is restored, it can make its way to other farms all over the world. This method could help us cut down on our own water waste around the world! Also if we remember how our food was originally created, we wouldn’t feel the need to genetically modify it all the time.

In the Carolyn’s article, Archaeologists have also found some of the stone in the canals to be older than Inca times. (Graber 2011) The Incas used what was already on the land and mastered it. Proving to be one of the most sustainable civilizations on the planet.

Further Reading

Learn about the food they cultivated for us: Inca Food and Agriculture

https://www.ancient.eu/article/792/inca-food–agriculture/

How the climate affected the Inca?:

Hotter Weather Fed Growth of Incan Empire

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn17516-hotter-weather-fed-growth-of-incan-empire/

References Cited

Graber, Cynthia

2011 Graber, Cynthia. Farming Like the Incas. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/farming-like-the-incas-70263217/#seOqzO8SLKfBcuWz.99. Accessed September 6, 2011

Kaushik

2013 Kaushik. The Mysterious Moray Agricultural Terraces of the Incas. Electronic Document. https://www.amusingplanet.com/2013/03/the-mysterious-moray-agricultural.html. Accessed March 4, 2013

Moray Ruins

2018 Moray Ruins. The Only Peru Guide. Electronic Document. https://www.theonlyperuguide.com/peru-guide/the-sacred-valley/highlights/moray-ruins/ accessed 2018

National Science Foundation

2005 National Science Foundation. News Release 05-088. Electronic Document.

https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?org=NSF&cntn_id=104207&preview=false. Accessed May 27, 2005.

Images Cited

Blangley, Kylie

2018 Blangley, Kylie. Inca Empire. Electronic Document, https://infogram.com/inca-empire-1gl94pkvrrjvm3v. Accessed 2018.

McKay, Savage

2012 McKay, Savage. Peru – Cusco Sacred Valley & Incan Ruins 045 Moray. Flickr. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/moray Accessed April 14, 2012.