Humans have been consuming fish for a long time. Two major discoveries in East Asia give insight into some of the earliest technological advancements in fishing.

Figure 1: Partial fishing hook used by early humans in East Timor (Choi 2014). Photograph by Susan O’Conner

One site in present-day East Timor, a small island north of Australia, gives us insight on early fishing techniques. The discovery of fishing hooks made of bone and shell (Figure 1) can be dated back to 42,000 years ago (Choi 2014). These hooks are the oldest ever found (Choi 2014). What is so impressive about these fishing hooks is that they were used to catch tuna, a fish that lives in deep water, moves quickly, and is even difficult to catch today. Early humans developed new techniques in order to catch these fish. The site is at the Jerimalai Shelter (Figure 2) found on the north side of the island (Corbyn 2011). Archaeologist Susan O’Connor spearheaded the dig and found around 38,000 fish bones including fish such as tuna and parrotfish (Zukerman 2011). East Timor is a small island with not many large animals living on it today, so humans living at the site 42,000 years ago most likely relied on fish as their main source of food (Choi 2014). Therefore, humans were forced to adapt and create new technologies, such as deep-sea fishing hooks, to allow them to capture fish in the area. These fishing techniques also give us a further understanding on how humans were able to travel across the ocean for extended periods of time, subsisting on fish during the journey, to get to Australia and other islands (Corbyn 2011).

Figure 2: The Jerilamai Shelter in East Timor where ancient fish bones and fishing hooks were found. Photograph by Susan O’Conner

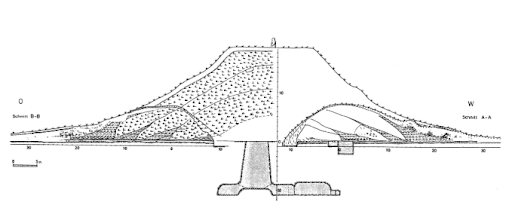

Another discovery that furthers our understanding of the development of fishing comes from a site in Northeastern South Korea, where the oldest fishing net sinkers (Figure 3) were found (DeCou 2018). In the Maedun Cave site, archaeologists discovered 14 stones made of limestone with “central grooves” (DeCou 2018). The nets would sink to the seafloor because of this extra weight and would catch fish more efficiently. Thanks to radiocarbon dating, we know these stones to be about 29,000 years old and are “considered to be the world’s earliest” of their kind (Yonhap 2018). Before this find, the oldest stone sinkers were roughly 10,000 years old (DeCou). Humans were using stones to sink nets thousands of years before what we previously thought.

Figure 3: Limestone net sinkers with grooves were found in South Korea (DeCou). Photograph courtesy of Han et al.

With the discovery of these old fish hooks and net sinkers, we now know that technologies in fishing occurred much earlier than previously thought. The findings also increase our understanding of the diet of humans and the types of fish people were eating in East Timor 42,000 years ago and in South Korea 29,000 years ago.

Additional Reading

On the importance of present-day fishing in East Timor

More information on some of the earliest seafaring humans

References

Choi, Charles Q.

2014 World’s Oldest Fish Hooks Show Early Humans Fished Deep Sea. Electronic Document, https://www.livescience.com/17186-oldest-fish-hooks-early-humans.html, accessed September 27, 2019.

Corbyn, Zoe

2011 Archaeologists land world’s oldest fish hook. Electronic Document,

https://www.nature.com/news/archaeologists-land-world-s-oldest-fish-hook-1.9461, accessed September 27, 2019.

DeCou, Christopher

2018 Possible Evidence of World’s Oldest Fishing Nets Unearthed in Korea. Electronic Document, https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/possible-evidence-of-worlds-oldest-fishing-nets-unearthed-in-korea/, accessed September 27, 2019.

Yonhap

2018 29,000-year-old net sinkers, world’s oldest, found in Korean cave. Electronic Document, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180807000306, accessed September 27, 2019.

Zukerman, Wendy

2011 Deep sea fishing for tuna began 42,000 years ago. Electronic Document,

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21213-deep-sea-fishing-for-tuna-began-42000-years-ago/, accessed September 27, 2019.

Images

Figure 1. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21213-deep-sea-fishing-for-tuna-began-42000-years-ago/

Figure 2. https://www.livescience.com/17186-oldest-fish-hooks-early-humans.html

Figure 3. https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/possible-evidence-of-worlds-oldest-fishing-nets-unearthed-in-korea/