Havana, Cuba is an unsettling mix of old buildings crumbling to the ground, residents still inside, and a Carribian get-away for the foreign tourist. On the waterfront, Havana boasts a beautiful historic district, “Old Havana”, but stray far from the main streets and plazas and you will find yourself surrounded by neglected buildings. The ruination of these buildings tells the story of a government with limited money that chooses to prioritize the city’s appeal to foreigners above its safety for locals.

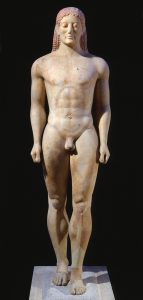

Old Havana is the historic district of Havana and became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982 (Perrottet 2018). Since then it has received funding from outside sources and support from the Cuban government. Restorations of historical architecture (Figure 1) have won Havana officials dozens of international awards (Eaton and Lewin 2018) and brought tourists flocking to the city. Cubans benefit from the economic boost brought by the tourism industry, but those economic gains fail to offset the hardship of many families’ deteriorating residences.

Figure 1. Part of the beautifuly restored Old Havana, the Plaza de San Francisco. Photograph from Planet Ware.

In the ongoing restoration process of Old Havana, many people feel left behind. In 2012, about 7 percent of housing in Havana had been declared uninhabitable and 7 in 10 buildings needed major repairs (Rainsford 2012). Even when residences are repaired many families are displaced, since the government does not allow as many households back into the buildings as were crowded in previously (Perrottet 2018). Government programs work to rectify the housing crisis that has many people living in buildings that could collapse any day (Figure 2), but they are not addressing the problem fast enough. According to USA Today, “3,856 partial or total building collapses were reported in Havana from 2000 to 2013, not including 2010 and 2011 when no records were kept” (Eaton and Lewin 2018). These collapses stand in stark contrast to the beautiful historic architecture Havana officials work to preserve. The Cuban government is short on money and has to prioritize projects. Their priorities are clear; Havana is quite literally collapsing while a historic district for foreign tourists grows.

Figure 2. People continue to live in the crumbling buildings in Havana, Cuba. Photograph from Translating Cuba.

Allowing for or requiring destruction of “certain people and places, often in the name of humanitarian work” (Beisaw 2017) is a political process known as ruination. The humanitarian effort of preserving a UNESCO World Heritage site comes at a price and the people who die because they cannot leave the buildings their government has condemned are paying it. Looking at the ruination of Havana reveals a rift between the Cuban government and its people. The government has the authority to choose what will be restored and what will be left to decay. So far it has chosen to restore the tourist epicenter that brings in new-comers, and leave the people already living in Havana to fend for themselves. Ruination shows power and where that power lies. Cuban officials hold the power in Havana, and the citizens of Havana see the evidence of it every day in the ruination of their home.

Refrences

Beisaw, April M.

2017 Ruined by the Thirst for Urban Prosperity: Contemporary Archaeology of City Water Systems. In: Contemporary Archaeology and the City: Creativity, Ruination, and Political Action, edited by Laura McAtackney and Krysta Ryzewski. Oxford Press. pp. 132-148.

Eaton, Tracey and Katherine Lewin

2018 How Havana is collapsing, building by building. USA Today. accessed November 10, 2019.

Perrottet, Tony

2018 The Man Who Saved Havana. Smithsonian Magazine. accessed November 10, 2019.

Rainsford, Sarah

2012 Cuba’s crumbling buildings mean Havana housing shortage. BBC. accessed November 10, 2019.

Images

Figure 1

https://www.planetware.com/havana/old-havana-cub-cdh-hv.htm

Figure 2

https://translatingcuba.com/havana-city-of-the-marvelous-unreality-jeovany-jimenez-vega/

Additional Content

Havana: The New Art of Making Ruins

Documentary about the people living in Havana’s ruins

https://vaslib.vassar.edu/record=b2199015~S3

Why Havana Had to Die

Why Havana’s buildings sunk into ruin initially

https://www.city-journal.org/html/why-havana-had-die-12360.html