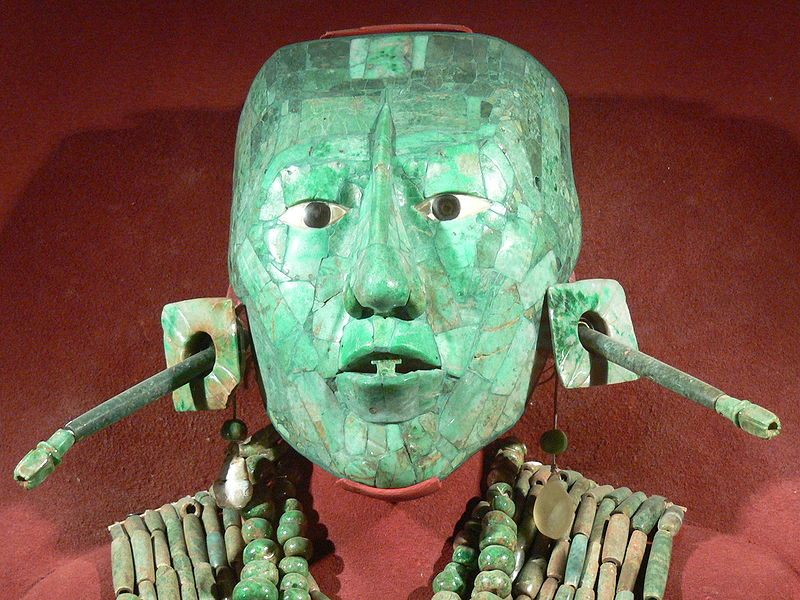

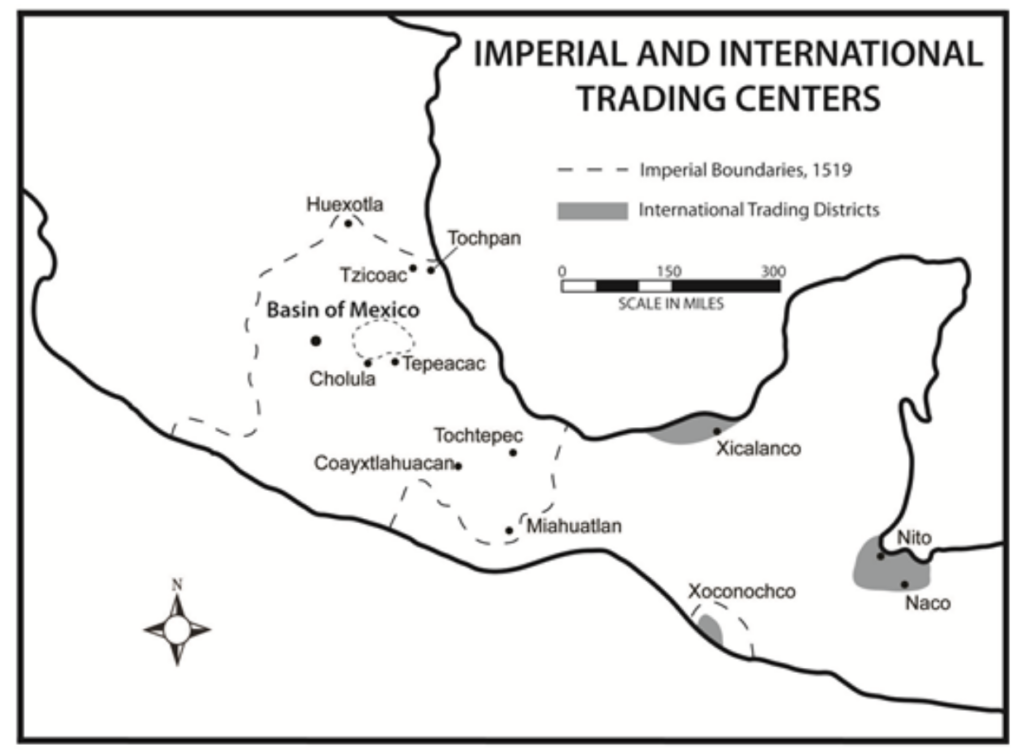

The short lived Aztec Empire was made of various city-states tied together with “persistent and aggressive multifaceted trade networks” (Berdan 2017). Although the Mexica group led the expansion of the Aztec Empire’s military and politics, they did not pioneer markets or trade in central Mexico. Evidence points to the first markets appearing in Oaxaca from 500-100 BCE, and even earlier, the first evidence of established trade networks comes from 1400-950 BCE in the preclassic Olmec civilization. Trade continued into the classical era of Mesoamerican history, as it was prominent in the Mayan world, with goods such as “obsidian, jade, quetzal feathers, marine shells, igneous rock, and various craft” (Berdan 2017) being traded. In the postclassic Aztec Empire, commerce was the primary method of integrating the various city-states comprising the empire, with trade happening locally, regionally, and foreignly throughout the region.

One important aspect of this far-reaching trade system were pochteca, professional long-distance traders who specialized in expensive goods such as “jaguar pelts, jade, quetzal plumes, cocoa, and metals” (Maestri 2018) and whose primary consumers were the wealthy elite. Because of their role, the pochteca had their own social class, “higher than any non-noble person” (Maestri 2018). Additionally, the pochteca guilds had their own laws, god, ceremonies, and closely guarded secrets and trade knowledge only available to sworn guild members. Pochteca traveled in caravans in every direction from their stations in major cities. They would also sometimes act as spies for their clients as marketplaces and other trade centers were good places to gather information via local gossip, which would be reported back to the buyers. Conversely, they also could be informants for the Aztec State, as their travels took them all over the empire and they had the permission to travel to foreign lands beyond control of the Mexica emperor.

One very important good throughout the history of Mesoamerican trade is salt. The Olmecs were the first group in the region to begin actively engaging with the material by extracting it and trading it along the eastern coast. By the classical period salt was likely one of “Mesoamerica’s most widespread regional specializations” (Williams 2009). Salt (sodium chloride) is necessary for human survival and an important tool for preserving food, and was used by the Aztec state to maintain order within the empire, as the state had the power to limit or block trade supply of the resources to conquered communities, ensuring their obedience to the empire.

References

Berdan, Frances F. “Late Postclassic Mesoamerican Trade Networks and Imperial Expansion.” Social Studies, May 2017, www.sociostudies.org/journal/articles/939197/.

Maestri, Nicoletta. “Pochteca: Elite, Powerful and Deeply Distrusted Traders of Mesoamerica.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 13 Jan. 2018, www.thoughtco.com/pochteca-elite-long-distance-traders-172095.

Williams, E. (2009). Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica. In: Staller, J., Carrasco, M. (eds) Pre-Columbian Foodways. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0471-3_7

Further reading

Smith, Michael E. “LONG-DISTANCE TRADE UNDER THE AZTEC EMPIRE: The Archaeological Evidence.” Ancient Mesoamerica 1, no. 2 (1990): 153–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44478204.

McGuire, Randall H. “The Mesoamerican Connection in the Southwest.” Kiva 46, no. 1/2 (1980): 3–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30247838.