The idea behind remediating an image that represents Vassar was to learn basic aspects of photoshop while also applying some concepts of remediation from our class discussion. I have chosen to take an image of the Thompson Memorial Library in the winter time and overlay some images of Vassar students (some of my friends). Behind the library you can see Matthew Vassar looming above in the clouds looking over his creation. The image is my commentary on Vassar student life: students enjoying themselves, getting ready for the spring by dressing like it’s 80 degrees out when it’s really in the 50’s, while also constantly being reminded of the massive amounts of work awaiting them in the library. I added Matthew Vassar, the ominous being we speak so fondly of as Vassar students, as a tribute to all the glory that is Vassar!

Author Archives: admin

Archaeology Games

Try your hand at this archaeology game made by the BBC.

The game puts you in the shoes of an archaeologist searching for an ancient burial site with a limited budget and under time pressure from developers. You need to do research at the local records office, take aerial photos of the land, and choose what methods to use in your excavation.

The game is quite unusual, in that it puts CRM archaeology in context and allows the player to see the “big picture” in an archaeology project- that which takes place outside of the actual excavation. I lost the game (and the quarry company destroyed my site) on my first try because I was too slow and careful with digging and went over budget.

In a basic search of online archaeology games out there, you’ll probably find that most aren’t really games at all, but “clickable” animations or quizzes. However, the best educational games (and Hunt the Ancestor only begins to scratch the surface of possibilities here) are immersive and immediate- you learn not by being asked to read facts, but by living a virtual life and having virtual “hands-on” experience. Actually making decisions and dealing with results makes programs like this one much more compelling and therefore better instruments of public archaeology.

Archaeology in the Classroom

This week we talked about one of the most effective ways to get knowledge of archaeology out to the public: teaching it in classrooms. The focus was on grades K-12, though we talked a little about college courses in archaeology as well. Of the many case studies we read, one of the most emphasized ways to introduce archaeology to students was to find ways to make archaeology work for teachers. In other words, since teachers have to teach their students a specific set of topics and skills in order to meet state requirements, archaeologists should work with teachers to figure out how archaeology can be used to teach things that are required. Archaeology, being quite interdisciplinary in the real world, can be used to teach map-reading, math skills, the scientific method, history, music, and values, such as respecting different cultures.

The articles we read also offered tips for making archaeology really stick in students’ minds. Hands-on activities were a common theme. Whether in the classroom, at an archaeology event, or in a museum setting, crafts like pottery making and activities like throwing atl-atls were very popular. If these activities are accompanied by a lecture, question and answer session, or a handout with background information, they can be more than just entertainment for kids. Students have different learning styles, and receiving and interacting with information using different sensory modalities can lead to improved information retention for all. Another tip for making an effective archaeology presentation is to learn about the people in your audience beforehand, and craft the presentation with their ages, skill levels, and interests in mind. Finally, many of the authors we read could not emphasize enough the importance of taking advantage of the expertise of any educators you are working with, rather than just treating them as another person to be educated. They likely have more teaching experience than you might, and can help your archaeology presentation be as effective as possible. However, it is very important to communicate with your teacher-collaborators when crafting an archaeology presentation. Often, your goals as an archaeologist (to gain support for archaeology, to teach stewardship) may be different from the teacher’s goals (entertain the kids, maintain discipline, teach a variety of subjects and skills). Make sure that this is something that you discuss in the planning stage so that everyone benefits from bringing archaeology into the classroom.

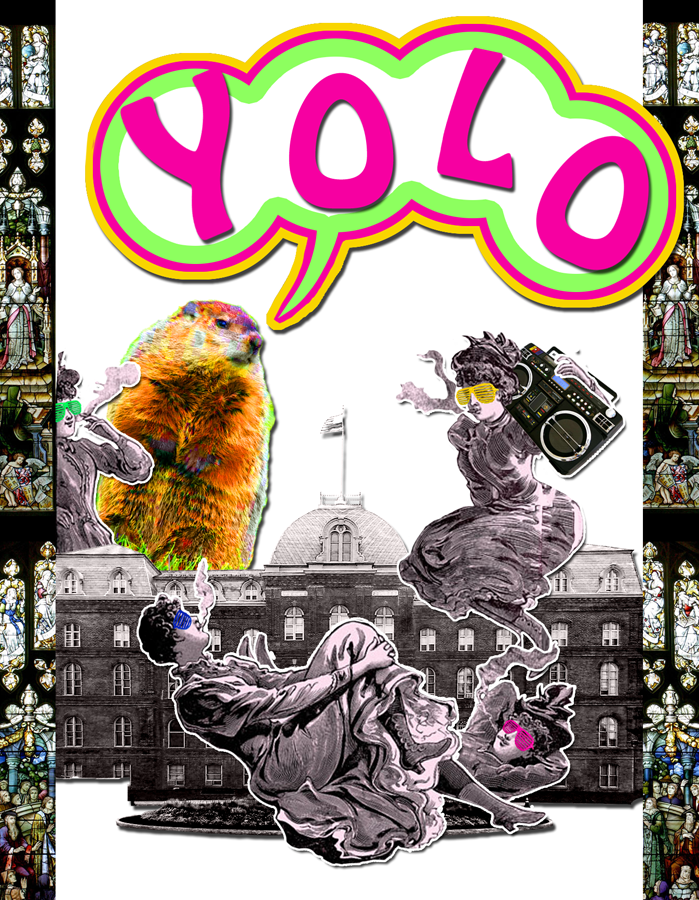

Remediating Vassar Imagery

It’s always fascinated me that VC students take a remarkable amount of pride in the college’s history of academic legitimacy, but have no qualms about re-purposing that history ironically (the Victorian lady trope, e.g.) Cultural legitimacy indeed.

(Feat. Main Building, classy smoking Victorian ladies, the library’s stained glass windows, and a whomp-whomp)

Experiment in Remediation: My Vassar Experience

Discussion Topic: Archaeology as Social Justice

The topic of my discussion was “Archaeology as Social Justice.” This week, we dealt with defining some more theoretical terms relevant to the idea of community and public archaeology. Some other goals of this week’s discussion were to answer questions like How can we address issues of class using archaeology? What is the difference between critical archaeology and post-processual archaeology? For critical theory, we looked to Randall McGuire, a professor of Anthropology and archaeologist who received his PhD at the University of Arizona in 1982. Critical theory stems from consumerism: fed products that ultimately perpetuate class structure. In critical theory, class relations are reorganized by ideology. An example of this dominant ideology is meritocracy, which is the idea that people start on the same playing field and succeed by solely by working hard. Ultimately, the goal is to bring these ideologies to light so that people can recognize and understand them.

Processual archaeology is essentially deductive positivist theory, which adopts a strict way of performing scientific study. The idea here is to create studies that are replicable with refutable or non-refutable hypotheses. Processual archaeology seeks to explain why societies are more complex than others. Post-processualism emerges against processual archaeology, coming out of post-structural thought. Post-processualism is kind of like an umbrella of techniques against processualism, including meaning, critique, and transformation. The critique aspect of post-processualism deals with the researcher knowing his or her biases and understanding context. Transformation of post-processualism deals with creating a new practice.

We talked a little bit about feminist literature and research relating to archaeology, which largely deals with the intersecting of categories of experience with each other and the relationships among domination, power, and balance. Marxist archaeology puts class above other categories of experience. Indigenous archaeology intersects with some of the feminist perspective but asks the question, how do these result in colonization? Ultimately it is important to understand how we create and use knowledge. In order to transform archaeology, we must understand how we create knowledge.

Burial Grounds, Archaeological Sites, and the Oil Pipeline

This article by Katie Fretland of the Associated Press serves as a reminder that the lands that we live and build on today have been lived, built, and died on by other people for millennia. The Keystone XL oil pipeline is meant to improve the United States’ oil transportation system, the whole thing extending from Canada to the Gulf Coast. The pipeline is already a contentious topic among people who are concerned about its impact on the environment, but there are others who have concerns as well. This article focuses on the concerns of Chief George Thurman of the Sac and Fox Nations, specifically that the portion of the pipeline running from Oklahoma to Texas will interfere with Native American burial sites. He and others believe that there might be unmarked graves in the proposed route of the pipeline.

TransCanada, the company in charge of building the pipeline, does have archaeologists to help determine when historical sites, artifacts, or graves might lie in the path of construction. They claim that construction ceases when any such sites are found, and that when they find a site, they then work with the relevant tribes or concerned parties to figure out how the situation should be handled. In Oklahoma alone, seventy archaeological sites have already been identified in the preliminary survey of the area where the pipeline is to be built. It will be interesting to see what is unearthed during construction, and whether any compromises are made on TransCanada’s part if, in fact, burial sites are uncovered.

Democratizing Heritage: New Media

This week our discussion centered on the use of visual and new media in public archaeology. This blog already provides examples of a wide range of alternative tools for communicating archaeology: blogs, digital narratives created through Voicethread, Youtube videos, and online museum exhibits to name a few. What possibilities do media outside of the traditional academic categories open for doing public archaeology? What challenges to alternative media present?

General consensus seems to be that new media are a powerful tool for communicating with the public- more compelling and interesting than traditional texts. New media are more accessible both to readers, who have the ability to give direct feedback, and to authors, who can be published online without much of the gatekeeping of print.

Chip Colwel-Chanthaphonh saw the potential in an online archaeology exhibit to reach a wide audience while also providing not just information, but an experience that steeped the viewer in culture through music, image, video, text and art. For him, “alternative” archaeology is best matched with alternative media. Ruth Van Dyke explores other possibilities in new media, including experimental video that challenges the conventional codes used in archaeology documentaries, hyperlinked web sites that force the viewer to navigate his or her own course.

Though critical movements in archaeology have led to a deeper self-consciousness in the producers of archaeological knowledge when writing texts, Sara Perry sees a lack of critical examination in the use of images. She uses the example of visualizations used for the peopling of areas as a troubling example in which contemporary and objectivizing conceptions are projected on the past and legitimated through the unquestioned mode of image. She suggests remediating such images to  force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

force the viewer to engage with them as constructed media rather than as transparent depictions of reality. Van Dyke also notes the power images, in particular photographs, have to legitimate themselves; a picture says, “I was there”. She suggests using this power to drive new interpretations that challenge present accepted interpretations.

The texts mentioned here focus on how new media can be and has been used to communicate archaeology, but only in one direction, from the archaeologist to the non-archaeological public. Could video, interactive programming, or other non-traditional forms ever be considered appropriate for communication strictly within academic circles?

Looking Both Ways

Looking Both Ways is an online, interactive exhibit about the Alutiiq People of Southern Alaska, created by the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, the Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository and the Alaska Native Heritage Center. The names of these three institutions are displayed largely on the homepage, indicating the collaborative nature of the project.

The exhibit provides a brief introduction to the region and people and map, which you can click on to learn about each village. Each village has about five photographs from different time periods with descriptions that name specific individuals and locations. The exhibit also has a section entitled “Object Categories,” which is comprised of different pages, such as “Our Ancestors,” or “Our Beliefs,” that use archaeological artifacts to tell the story of their way of life and show their evolution from the time of their ancestors through the present. These materials are, however, completely removed from their context, photographe d against a white background, and the descriptions rarely tell you from which site they were found, which village they belonged to, what they meant to their owners or how they were found. Furthermore, images under the “Our Way of Living” section are given no dates, and are photographed as if primitive tools, no longer in use, but they sill allow the viewer to associate them with contemporary Alutiiq life. (see right)

d against a white background, and the descriptions rarely tell you from which site they were found, which village they belonged to, what they meant to their owners or how they were found. Furthermore, images under the “Our Way of Living” section are given no dates, and are photographed as if primitive tools, no longer in use, but they sill allow the viewer to associate them with contemporary Alutiiq life. (see right)

I think the main idea of the site is to attempt tell the story of the Alutiiq people from their perspective, and teach the public about their heritage and identity. However, the exhibition focuses primarily based on the incontrovertible evidence of archaeological material to build their story, rather than through the multiple perspectives of oral histories, and in doing so loses any sense of indigenous authorship, despite its alleged collaboration. Whether the individual tribes where a part of the process, remains unclear.

While there are a lot of good ideas in this site, and it is very engaging, in some areas I believe is misuses images, as Perry  warns us in her article. Some of the pictures are so obviously staged that they seem a bit phony, more like Halloween costume advertisements than images of real contemporary people, as they are completely removed from any sort of context (see left). Images such as these perpetuate stereotypes, and do not enable the viewer to create this new, factual-based conception of modern and historical indigenous life that the site aims to depict.

warns us in her article. Some of the pictures are so obviously staged that they seem a bit phony, more like Halloween costume advertisements than images of real contemporary people, as they are completely removed from any sort of context (see left). Images such as these perpetuate stereotypes, and do not enable the viewer to create this new, factual-based conception of modern and historical indigenous life that the site aims to depict.

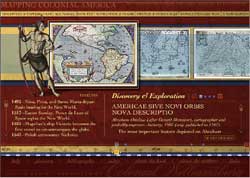

Review of Colonial Williamsburg’s Online Exhibit, “Mapping Colonial America”

I have chosen to review the “Mapping Colonial America” online exhibit on the Colonial Williamsburg website. The home page of the actually Colonial Williamsburg website consists of scrolling images that relate to a number of really cool blogs and articles relating to colonial US history. Among these links is also access to a page titled “Help Preserve America’s History,” allowing site visitors to make donations.

I have chosen to review the “Mapping Colonial America” online exhibit on the Colonial Williamsburg website. The home page of the actually Colonial Williamsburg website consists of scrolling images that relate to a number of really cool blogs and articles relating to colonial US history. Among these links is also access to a page titled “Help Preserve America’s History,” allowing site visitors to make donations.

To access the exhibit, one must click a link title “Museums” and from there click “Online Exhibits and Multimedia.” That page then lays out links to the online exhibits including a summary of each one. I have chosen to focus on the online exhibits, “Mapping Colonial America,” which discusses and displays colonial maps from the collection at Colonial Williamsburg.

To access the exhibit, one must click a link title “Museums” and from there click “Online Exhibits and Multimedia.” That page then lays out links to the online exhibits including a summary of each one. I have chosen to focus on the online exhibits, “Mapping Colonial America,” which discusses and displays colonial maps from the collection at Colonial Williamsburg.

The multimedia presentation first displays a home page with the title of the exhibit with a sketch of a ship and what appears to be an old compass. This presentation is based on the book “Degrees of Latitude: Mapping Colonial America,” written by Margaret Beck Pritchard and Henry G. Taliaferro. The presentation display twenty-two maps with a variety of views as well as a brief description of each. At the top of the page, there a number of topics including “Discovery & Exploration,” briefly discussing the importance and use of maps in colonial America. The other topics include “Boundary Disputes,” “Navigation &Trade,” “French & Indian War,” “Revolutionary War,” and a “New Nation.” These topics set the stage for the exhibit, giving an essence to and providing a context for the maps on display.

When clicking “got to maps,” the viewer can begin in 1701 viewing a map entitled “A New Map of Virginia, Maryland, Pensilvania, New Jersey, Part of New York, and Caroline.” On the bottom of the page is a timeline with marks indicating the time period of the rest of the maps, giving the viewer a sense of where they are in the timeline of colonial American maps. To the left is a more specific timeline relating to the date the map was created offering information of important events that occurred in colonial America. On the right is information about the map itself such as the creator of the map, their profession, when the map was created, where it was created, and some interesting facts about it. The presentation also allows the viewer to click on the map for more specific information about it as well as alternative ways to view the map including close ups of writing on the map. The viewer may also zoom in on the actual map, which is pretty cool because it allows the viewer to have a more personal experience with the artifact allowing for closer exploration and observation.

When clicking “got to maps,” the viewer can begin in 1701 viewing a map entitled “A New Map of Virginia, Maryland, Pensilvania, New Jersey, Part of New York, and Caroline.” On the bottom of the page is a timeline with marks indicating the time period of the rest of the maps, giving the viewer a sense of where they are in the timeline of colonial American maps. To the left is a more specific timeline relating to the date the map was created offering information of important events that occurred in colonial America. On the right is information about the map itself such as the creator of the map, their profession, when the map was created, where it was created, and some interesting facts about it. The presentation also allows the viewer to click on the map for more specific information about it as well as alternative ways to view the map including close ups of writing on the map. The viewer may also zoom in on the actual map, which is pretty cool because it allows the viewer to have a more personal experience with the artifact allowing for closer exploration and observation.

I personally really enjoyed this exhibit. I feel that this multimedia presentation did a great job of condensing relevant information and putting it in one accessible place. I thought the exhibit was well organized in that the viewer could look through all of the maps but could also click on a map for further information about it. The number of settings and different ways to view the map were effective as, and I think maybe create a greater impact than seeing the artifact in person. I say this because the way in which the images are set up, give the viewer an idea of what to look for on the map. However, I think that this exhibit would be pretty confusing for someone who is not super tech savvy. I also wish there was a comments section or something like that to offer a place for community discussion.