Popular media has taught us that anyone can be an archaeologist. It’s easy, right? All you need is a shovel, a couple buckets, and maybe a cool whip to fight off some Nazis, and you’re all set to discover some nifty caves and make a ton of money off golden idols! Right?

Time for an archaeological dig!

Well, not so fast. What Indiana Jones doesn’t show us are the years of study, fieldwork, and tedious lab work that go into archaeological study. And it definitely doesn’t show that if you want to be a respected archaeologist, you need to join a professional archaeological society and agree to abide by its standards of ethics.

That’s ridiculous, you say; the archaeological record is available to everyone and shouldn’t be restricted to a bunch of snooty professionals. I should be able to dig up whatever I please, you say, because history belongs to everyone!

Thing is, that’s not really true. There are a number of groups with specific cultural ownership of archaeological remains, and archaeologists have to respect that ownership and act accordingly.

First and foremost, the descendants of the group or culture being studied have a right to their history. This means a number of things for archaeologists. Firstly, graves should not be excavated without the permission of the descendant community, no matter how much information could be gained from the excavation. The pillaging of sacred Native American graves by white North American archaeologists in the past caused a great deal of backlash, resulting in legislation like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990. This also means that archaeologists need to maintain open and respectful communication with the descendant communities that they are working with, when both planning an archaeological project and interpreting its results.

Don’t be this guy. Bald eagles will get really mad at you.

Apart from descendant communities, the public has a right to the archaeological record. You can’t just dig stuff up, put it on a shelf, and not tell anyone about it; you could be hiding away new information that might change the way history is taught or help us think about some of the challenges facing the modern world. In its Principles of Archaeological Ethics, the Society for American Archaeology lists just a few of the possible audiences for archaeology, which include students, politicians, journalists, and many more. Archaeology should be a tool to promote learning and come to new understandings about the past and the present, not just to add to your collection.

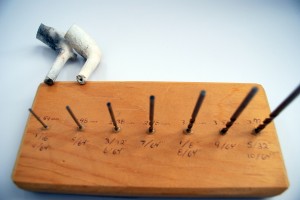

Whoever put together this arrowhead collection was not complying with archaeological standards of ethics. These are artifacts, not wall décor!

Finally, future archaeologists have a right to the archaeological record, too. That’s why stewardship is the first principle in the SAA’s list; archaeologists are obligated to preserve sites so that future archaeologists with better technology and different perspectives can also learn from them.

So the next time you’re tempted to start digging for treasure, remember that the archaeological record doesn’t just belong to you, and put that shovel away.

Further Reading:

On NAGPRA: http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/

On the Society for American Archaeology’s ethical standards: http://www.saa.org/AbouttheSociety/PrinciplesofArchaeologicalEthics/tabid/203/Default.aspx

Sources:

Ashmore, Wendy and Robert J. Sharer. Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology. New York: McGraw- Hill, 2012. Print.

National NAGPRA. National Park Service, n.d. Web. 14 Nov. 2013. <http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/>.

“Principles of Archaeological Ethics.” Society for American Archaeology. SAA, n.d. Web. 14 Nov. 2013. <http://www.saa.org/Default.aspx?TabId=203>.

Sabloff, Jeremy A. Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 2008. Print.

Image 1: http://static.ddmcdn.com/gif/archaeology-2.jpg

Image 2: http://publications.newberry.org/indiansofthemidwest/wp-content/gallery/nagpra151/research.jpg

Image 3: http://media.liveauctiongroup.net/i/8093/9734883_1.jpg?v=8CD0610F92B8410