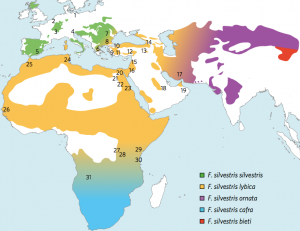

In 2014, the city of Flint, Michigan began sourcing its water from the Flint River, a decision that would result in life changing impacts for many of the city’s residents. Ensuing reports of declining water quality revealed that it was heavily contaminated with lead and other toxins(CNN Library 2019). Since then, the city and the state have been working to replace all lead and galvanized pipelines. Despite the urgency of this undertaking, work has been drastically slowed in the Fifth Ward, a location that incidentally has the highest percentage of lead pipes and the highest levels of poverty in the city (Figure 1) (Ahmad 2019a; Maher 2016).

Figure 1: Heat map showing the concentration of safe copper lines and unsafe lead or galvanized lines in the city. Ward 5 shows the highest concentration of dangerous lines(Ahmad 2019a)

This delay in action is not unfounded. In January 2008, construction of basements in Ward 5 uncovered human remains and artifacts revealing a Native American burial ground. In 2017, the State Historic Preservation Office and the Michigan Department of Environment took measures to ensure that, thereafter, all service line excavations would involve an on-site archaeologist(Ahmad 2019a). This agreement to enforce professional oversight was signed by the state, the city, and the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan(Figure 2) who controls the remains of several indigenous groups including the Ojibwe, the Potawatomi, and the Odawa(Fonger 2019; Indian Country 2009).

Figure 2: Members of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian tribe surveying the site of a burial ground in 2008(Fonger 2019).

Despite efforts to preserve this archaeological site, city contractors were found disregarding the conditions of the agreement this past summer. Twenty-nine separate addresses were excavated without an archaeologist before a state inspector was able to halt operations. By this time, it is likely that crews came across numerous artifacts and human remains. In June, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy issued a letter to the Flint Public Works director in regards to this malpractice, and the project was again dramatically slowed(Fonger 2019).

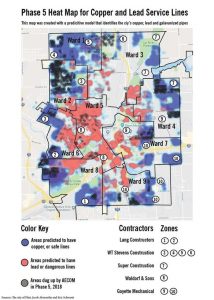

By further delaying the pipe replacement of the Fifth Ward, the dire situations of the residents were only exasperated. In September, only 105 out of 550 homes that were believed to have unsafe lines were dug(Ahmad 2019b). This ward is in desperate need of clean water(Figure 3), and it is evident that the process of getting clean water is being compromised by the presence of earlier inhabitants. That said, it would be wholly unethical to barrel through the remains of the native people that considered the land of the Fifth Ward their home first. These people and their living descendants are nothing less than allies. In 2016, it was, in fact, indigenous tribes who were among the first to hold water ceremonies as a form of support for the city(Peeples 2016).

Figure 3: Contaminated water has had a disproportionate effect on Flint’s poorest community in Ward 5(Maher 2016)

With contractors and many residents in favor of the fastest solution and indigenous groups and supporting organizations in favor of the respectful solution, there are clearly competing interests at play. The history of one people cannot be prioritized over that of another. This, however, seems to be the theme of many political water stories. From New York City to Flint, issues pertaining to water rights and water infrastructure always call into consideration the histories of those forgotten. Thus, no matter where or when, there will forever remain an ongoing story of water and conflict.

References

Ahmad, Zahra

2019 Flint water-line replacement on hold in area where high chance of finding lead lines. MLive, January 29, 2019. https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2018/11/post_529.html, accessed November 9, 2019.

Ahmad, Zahra

2019 Flint misses ‘self-imposed’ deadline for replacing lead service lines. MLive, September 4, 2019. https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2019/09/flint-misses-self-imposed-deadline-for-replacing-lead-service-lines.html, accessed November 9, 2019.

CNN Library

2019 Flint Water Crisis Fast Facts. CNN, July 2, 2019.

https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/04/us/flint-water-crisis-fast-facts/index.html, accessed November 9, 2019.

Fonger, Ron

2019 State wants to know if Flint dug up human remains in Native American burial area. MLive, June 21, 2019. https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2019/06/state-wants-to-know-if-flint-dug-up-human-remains-in-native-american-burial-area.html, accessed November 9, 2019.

Indian Country News

2009 Excavation begins on Native American burial site in Flint, Michigan. Indian Country News, August, 2019. https://www.indiancountrynews.com/index.php/archaeologyremains-sections-menu-116/7274-excavation-begins-on-native-american-burial-site-in-flint-michigan, accessed November 9, 2019.

Maher, Kris

2016 Flint’s Poorest Area Is at Center of Crisis. The Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/flints-poorest-area-is-at-center-of-crisis-1456704705, accessed November 9, 2019.

Peeples, Kila

2016 Native Americans held a water ceremony in Flint. 25News, April 16,2016. https://nbc25news.com/news/local/native-americans-held-a-water-ceremony-in-flint, accessed November 9, 2019.

Additional Reading

Native American Tribes & the Indian History in Flint, Michigan: https://www.americanindiancoc.org/native-american-tribes-the-indian-history-in-flint-michigan/,

Flint’s Children Suffer in Class After Years of Drinking the Lead-Poisoned Water:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/us/politics/flint-michigan-schools.html?module=inline,

Flint Michigan History and Early North American Indians: https://www.imagesofmichigan.com/flint-michigan-history-and-early-north-american-indians