For centuries archeologists have hypothesized about the causes of the demise of the Greenland Vikings. Most theories are relatively similar, though there are many points that archaeologists disagree on: chiefly perspectives on adaptation, and the roles of environment, economy, and identity.

Climate change has come into focus, with some describing it as the main cause of the collapse while others seeing a more minor role. Archaeologist, Matthew Mason argues that climate change was the most significant reason for the Greenland Vikings disappearance. Mason states that the initial Medieval Warm Period was misleading, causing the Vikings to adopt farming, which was unsustainable in the Little Ice Age (Mason 2018). However, archaeologist Nicolas Young, believes that blaming climate change is not only an oversimplification, but ethnocentric. Young explains that as the Medieval Warm Period only affected parts of Europe it is ethnocentric to give it a central role. Young believes that economics mainly underlie the collapse as the climate was cold and harsh the entire time the Vikings lived in Greenland (Connor 2015).

Another economic argument suggests that an over reliance on tusk ivory – thought to be the main item of trade with Europe – led to the Greenland Vikings demise. Some archaeologists believe that Russian ivory coming to the market in the 14th century devalued the Viking ivory. Furthermore, as climate worsened, storms made Walrus hunting harder, leading to an ivory shortage and declining profits (Kintisch 2016).

A less popular perspective, highlighted by Mason and Connor, is the role of religion in the collapse. Connor explains that resources were directed to the building of Churches and Cathedrals, led to deforestation and soil erosion (Connor 2015). Mason argues that the Vikings rejected hunting as outdated and associated it with Paganism, though it sustained the Inuits. This rejection lead to food shortages and environmental destruction from failed farming attempts (Mason 2018).

Mason argues that there was an “unwillingness to move away from practices of European identity” and this inflexibility in identity doomed the Vikings. The idea of the Viking’s inability to adapt is one of the most popular theories. Mason argues that the Vikings inability to adapt is evident in their failure to switch from crops and farming methods meant for richer, European soil (Mason 2018). However, archaeologists Arneborg and McGovern believe that the vikings did partially adapt. McGovern uses the contradiction in Seal hunting as evidence: although the Vikings did not use spears to hunt like the Inuits, appearing to reject this adaptation, they did hunt seal extremely successfully even as climate changed (CUNY Media 2011). Arneborg finds evidence for adaptation in the Viking’s rejection of livestock practices when they became profitless in the worsening climate (Kintisch 2016).

Whether it was environment, economics, ingrained identity, adaptation, or some yet-to-be-discovered cause, the story of the Viking collapse provides Archaeologists with a model to study the rise and fall of societies. The ultimate cause of the demise of the Greenland Vikings may serve as a warning and framework for directing our own thinking on sustainability and adaptation in modern societies

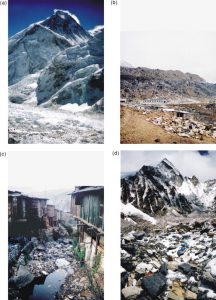

Above is an image exemplifying the harsh climate of Greenland today, comparable to the environment of the Viking period.

Above is an image exhibiting ruins of Greenland’s Hvalsey Church, an example of one of the religious buildings built as highlighted by Steve Connor.

Reference List

Connor, Steve

2015 Geologists have all but ruled out claims the Medieval Warm Period accounts for Greenland’s colonisation from 986AD. Electronic document, https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/climate-change-did-not-force-vikings-to-abandon-greenland-in-15th-century-a6761026.html, accessed November 11th, 2018.

CUNY Media

2011 How Nature Vanquished the Vikings of Greenland. Electric document, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TncIO4SRBic, accessed November 11th, 2018.

Eli Kintisch

2016 Why did Greenland’s VIkings disappear? Electronic document, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/11/why-did-greenland-s-vikings-disappear, accessed Nov 6th, 2018.

Mason, Matthew

2018 What Environmental Data Can Tell Us about the Greenland Vikings. Electronic document, https://www.environmentalscience.org/environmental-data-greenland-vikings, accessed November 5th, 2018.

Image Sources

Stockinger, Nther and Spiegel

2013, Ruins of Hvalsey Church, Hvalsey, Qaqortoq, Greenland. Electronic document, https://abcnews.go.com/International/archaeologists-find-clues-viking-mystery/story?id=18183196, accessed Nov. 11th, 2018.

Kelly, Gwyneth

2015, Minutes. Electronic document, https://newrepublic.com/minutes/125135/glaciers-reveal-greenland-wasnt-warm-vacation-vikings-all, accessed Nov. 11th 2018.

Additional Sources

1. https://newrepublic.com/minutes/125135/glaciers-reveal-greenland-wasnt-warm-vacation-vikings-all

2. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-greenland-vikings-vanished-180962119/