During the late 19th and early 20th centuries towns in the American West were rapidly created and subsequently abandoned. These towns have largely been ignored by historians and are just beginning to be studied by contemporary archeologists. By studying ghost towns, archeologists can tells us how and why this phenomenon occurred and provide valuable insight into what causes a settlement to fail. This is just one of many examples of how archeology is still relevant today.

The town of Frisco, Utah was studied by archeologists in 2008. At the site they find many artifacts including tobacco pipes and remains of a collapsed mine. Using these artifacts they were able to determine the Frisco was a moderately impoverished mining town that consisted mostly of men with few women and children.

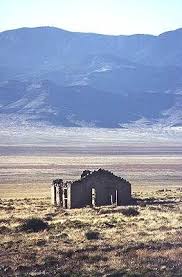

In a recent archaeological study of ghost towns across Utah, Arizona and Nevada, researches excavated 104 sites. These archeologists were then able to compare and contrast the process of abandonment as well as aspects of the lifestyle in each of these towns through their respective assemblages, specifically, Newhouse and Frisco, two ghost towns in Utah. (Peyton 2012) At the Newhouse site, archeologists primarily found food storage containers and other domestic items including children’s toys and hairbrushes, indicating the presence of women. They also found remnants of a school building. In contrast at the Frisco site there were many tobacco pipes and alcohol containers and very few artifacts that indicated the presence of women. An overall site reconnaissance survey at Frisco showed evidence of mining and that the town was likely abandoned due to a collapsed mine while at the Newhouse site a complex irrigation system and dried wells allowed archaeologists to come to the conclusion that the town had been abandoned due to water shortage.

In contrast when archeologists excavated Newhouse Utah they found many domestic items including women hairbrushes and children’s toys indicating that there were many more families moving to this town. This helps us to rethink the stereotypical image of a frontier town.

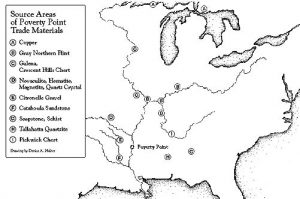

Like many contemporary archeologies, the archeology of western ghost towns can be used to dispute common misconceptions about these abandoned places. For example, not all ghost towns were mining towns as another team of archaeologist found that only approximately 45% of the towns they identified as ghost towns centered around meaning as their primary economic function. (Hardesty 2010) Others were religious settlements, railroad towns, military outposts and in the Pacific Northwest these towns are primarily associated with fishing and logging.

Another common misconception is that all ghost towns were abandoned because whatever they were mining ran out. (Ling 2013) Archeology has shown that the abandonment of the majority of ghost towns was a multicausal combination of social factors coupled with the overuse of natural resources, most notably water scarcity. (Peyton 2012) This collapse due to the exploitation of natural resources serves as a warning for us today and prevents us from blaming the failures of these towns on purely economic factors.

The archeology of ghost towns allows us to challenge many ideas we have about the west during this period of time such as the glorification of these mining towns as well as the idea that they simply popped up one day and then crashed the next. (Buckholtz 2015) Archeology has revealed that the decline of these towns is much more complex and took place over years. By studying this archeology of abandonment, archaeologist gain valuable insight to what challenges may turn our modern cities into the ghost towns of tomorrow.

References:

Buckholtz, Sarah

2015 Authentic Wild West Ghost Town: Bodie, CA. Two Lanes Blog. August 11

Hardesty, Donald L.

2010 Mining Archeology in the American West. Digital Commons. University of Nebraska

Press- Sample Books and Chapters, Spring.

Ling, Peter

Ghost Towns of America. Geotab Blog

https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

Peyton, Paige Margaret

2012 The Archaeology of Abandonment: Ghost Towns of the American West. Leicester

Research Archive: Home. School of Archaeology and Ancient History, November 1.

Image citations:

Bezzant, Bob

Newhouse, Beaver UT. Ghost Towns of America

Gabler, Michael

2018 Frisco: A Utah Ghost Town. Urban Ghosts. September 18

Additional Reading:

They Bought a Ghost Town for $1.4 Million. Now They Want to Revive It.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/18/us/cerro-gordo-ghost-town-california.html

A Soviet Ghost Town in the Arctic Circle, Pyramiden Stands Alone

The Archaeology of Settlement Abandonment in Middle America

http://www.iia.unam.mx/directorio/archivos/MANL510125/2003_Manzanilla-Abandonment.pdf